by Mike Telin

On Wednesday March 2 at 8:00 pm in CIM’s Mixon Hall, and Monday March 7 at 7:30 in Lorain County Community College’s Cirigliano Studio Theatre, the Cleveland-based new music ensemble Ars Futura will present Schoenberg’s melodrama. The program will also include Keith Fitch’s Dancing the Shadows, Bright Sheng’s Tibetan Dance (March 2 only), and Jeffrey Mumford’s four dances for Boris (March 7 only).

Scored for flute, clarinet, violin, cello, piano, and voice, Pierrot Lunaire premiered in Berlin on October 16, 1912 following 25 rehearsals. The text is a setting of 21 poems by Belgian poet Albert Giraud in a German translation by Otto Erich Hartleben, which the singer delivers in Sprechstimme, a vocal technique that combines singing and speaking.

“Like many new music groups, ours is a Pierrot ensemble plus percussion,” Ars Nova flutist Madeline Lucas Tolliver said during a telephone conversation. “Although our focus has been on performing works that are more recently composed, now that we are more established, it seemed like it was time to tackle this seminal piece.”

The protagonist in Giraud’s poems is the somewhat naïve and clownish character Pierrot, found in the Italian Commedia dell’arte tradition, each poem presenting Pierrot’s perspective on moonlight, love, religion, and death. “Some of the poems are racy and we’ll have translations so everyone can partake in the fun,” Tolliver said.

The work is also rooted in Schoenberg’s fascination with numerology: seven-note motifs are found throughout the piece. It’s written for an ensemble of six plus conductor, or seven people. “In keeping with the theme of seven, the piece is his opus 21 and it has 21 total movements divided into three parts, each part consisting of seven movements,” Tolliver pointed out. “The further you look into the numerological relationships you see that they go very deep.”

Joining Tolliver for the performance will be soprano Janine Porter, clarinetist Benjamin Chen, violinist Yun-Ting Lee, cellist Daniel Pereira, and pianist Shuai Wang, under the direction of Pablo Devigo.

Although it was written in 1912, Tolliver believes that Pierrot Lunaire still sounds as contemporary as ever. “Schoenberg wrote it about eight years before he started to look toward serialism, which is what a lot of people think of when they think of Schoenberg. He writes melodies that if played by themselves make sense — they sound melodious — but when he combines them with another melody, there’s no tonal center, no key. The layers of those melodic lines frequently line up to create something that is jarring or at least uncomfortable, especially when you add the Sprechtstimme, a style of singing that is still very radical to many people’s ears. Even as a performer, it sometimes makes my hair stand up when we’re rehearsing. It has a physical effect on the listener. I can’t really explain why the piece still sounds new other than to say that is the genius of Schoenberg.”

Tolliver said that she is looking forward to the performances of the Schoenberg. “For me, it’s a special project. I performed the work almost ten years ago, and it was the first piece of new music that I ever performed. It’s quite exciting to perform it again ten years later, now that I’m much more experienced, and I have a more extensive knowledge of contemporary sounds and the ethos that Schoenberg set up with this work. Each movement is so different, yet they are woven together like a tapestry. Each is very special yet the entirety of the work is extremely powerful. To me that is one of the highest achievements of a work of art. It doesn’t get much better than this.”

At both concerts percussionist James Ritchie will join his instrumental colleagues for Keith Fitch’s Dancing the Shadows (1994). In his composer notes Fitch writes:

Dancing the Shadows might be subtitled “Music for an Imaginary Ballet.” After having written several large-scale, intensely dark and virtuosic scores, I thought it would be a nice change to try something in a lighter vein. I have always been interested in dance music, particularly that of Stravinsky, and many of the gestures found here may strike the listener as particularly Stravinskian, though no direct comparison is intended.

“I’ve played a lot of pieces by Keith Fitch and I’ve always enjoyed them,” Tolliver said, “but this is probably the earliest piece of his I’ve ever performed. It’s sort of jazz-inspired and was influenced by his days as a bass player. It’s a really fun piece and I’m excited to be playing it.”

At the March 2 concert, violinist JinJoo Cho will join the ensemble for Bright Sheng’s 2000 composition, Tibetan Dance. In his composer notes, Sheng writes:

The first two movements of the work are in reminiscence; as if one is hearing songs from a distant memory. The work is anchored on the last movement, when the music gradually becomes real. Here, the music is based on a Tibetan folk dance motive from Qinghai, a Chinese province bordered with Tibet, where I lived during my teenage years.

At the March 7 concert, pianist Shuai Wang will perform Jeffrey Mumford’s 2004 composition four dances for Boris. It was written for pianist Lura Johnson to play as part of Enter Race, a dance work commissioned and choreographed by Boris Willis. In his composer notes, Mumford points out that:

Among the most important elements of these dances (particularly the third, marked ‘pensiero ma grazioso’) was to provide a vehicle for Ms. Johnson to express her considerable lyrical and rhythmic gifts. Formally, the work is a set of variations, and is an homage to the kind of transparent music characteristic of a good deal of mid-twentieth-century American Neo-Classicism.

Madeline Lucas Tolliver said that she’s very happy with the chosen repertoire for both concerts. “I think Shuai Wang did a great job with the programming. On the first half, listeners will hear some of the newer sounds. Then on the second half, when they hear Pierrot, they’ll know where that stuff came from.”

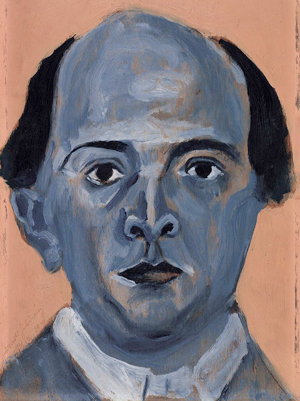

Graphic: Arnold Schoenberg’s self-portrait, 1910.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 29, 2016.

Click here for a printable copy of this article