by Jarrett Hoffman

Our conversation eventually made its way to Mendelssohn’s First Piano Concerto, which he’ll perform at Blossom with The Cleveland Orchestra and conductor James Gaffigan on Saturday, August 18 at 8:00 pm. But first, the pianist, composer, writer, and painter tackled some complicated and personal questions about his varied artistic self.

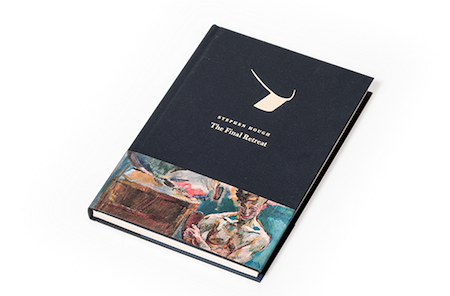

Hough’s first novel, The Final Retreat, was published in February (read his article about it in The Tablet here). His latest CD, a collection of miniatures titled Dream Album, includes his original music and was released in June.

Jarrett Hoffman: I recently talked to James Gaffigan, who said he can hear in your playing that you’re an author and composer. Can you feel those pursuits informing you at the piano?

Stephen Hough: You know, it’s very difficult to say because it’s who I am, so I don’t know what it’s like not to have that there. I know so many wonderful musicians who don’t write, so there’s no sense in which it automatically makes you better — it doesn’t. But for me it’s the source, in a way, of my musical inspiration. It’s this poetic center out of which comes my writing of words and music, and my playing of music. I’d find it very hard to give up any one of those three — they all seem part of who I am and part of how I express myself artistically.

JH: Performing, composing, and writing all involve revealing something very personal to the public. How would you compare them in terms of how deeply you dig into yourself, and how comfortable you feel showing it to the world?

SH: It’s a very interesting question. Of course, the concert is something happening right there. People are breathing in the same room, or at Blossom in the same outdoor space. So I think when you’re playing, the vulnerability is considerable. It’s not just that you have to play your instrument well, but there’s also the emotional connection that you have with that audience — although I have to say that this concerto is a very light piece on the whole. It’s not plunging the depths, Mendelssohn isn’t revealing a lot of himself, and therefore when we’re playing it, we’re not revealing a lot of ourselves — in partnership with Mendelssohn.

Writing is a whole different thing because you’re not just joining with a composer in sharing that expression with the audience, but you’re going deep inside yourself. And of course, a lot of subconscious things come out when you’re writing music or words — maybe more so with music because you put a lot of expression into that, and people might be able to see more of you in there than you even want to reveal. I’ve written a lot of short, encore-type pieces for fun, but with my serious pieces — my four piano sonatas, my cello sonata, my four song cycles, and other larger works — I think I can say that I’ve had tears in my eyes writing all of them. They’ve all gone to a place in which I’ve felt I’m revealing something very deep inside.

I don’t think music has to make you cry, but for me if music doesn’t reach something deeply emotional and human inside you, then it can be fun and entertaining and can pass the time, but I can never think of it as being great. And that’s perhaps part of the problem I have with some contemporary music — that as clever as it is, as witty as it is, as exciting as it is, it doesn’t go to that part of the soul which a great novel or painting does, where you feel transformed. A great work of art meets you in your deepest longings, and somehow there’s a recognition. You listen to a work of Beethoven, let’s say, and he leads you down this path and then turns to you and looks at you. And as you look at the composer and he or she looks at you, you feel something like, ‘Yes, I know what you mean, we’re here together — this is something that we share as two human beings.’ And that to me makes life worth living. That’s what art is for me.

JH: How would you characterize the relationship between performer and composer, and between writer and his or her characters?

SH: There’s a very difficult balance involved here. I think in the past, maybe a hundred years ago, the emphasis was too much on the performer, who was the center of everything. The music was a vehicle in some ways for great virtuosos to show off. That can be true with actors, where you sense it’s all about them and not about the character or the play, and it can be thrilling — you can see a Jack Nicholson movie and it’s Jack Nicholson in whatever role he’s playing.

On the other hand, I think today we have often gone in the wrong direction. We think that we serve a composer by stepping outside as far as we can into the wings, somehow allowing the composer’s vision to come through — and that absolutely doesn’t happen. If you’re going to play a composer like Liszt, you can’t be in the wings. You are Liszt’s mouthpiece, and you not only have to speak with his voice, but somehow join yours to his, otherwise the message won’t get across. It’s a little bit like being an ambassador representing your country. The country is what you’re meant to be focusing on, but if your voice isn’t compelling or interesting, or it doesn’t create an excitement — or a calm if you’re in the middle of a conflict — then you’re not representing your country.

It’s very much a balance that we always have to get right, and actually with every composer it’s slightly different. If you’re playing Beethoven, perhaps you need a little more sense of reverence for the score — at least you don’t just change things for the sake of it. If you’re playing Liszt or Saint-Saëns in some cases, you need to step in and become the center of attention, otherwise the piece won’t make sense. It’s again like acting: if you’re performing Shakespeare, it’s different from performing Noël Coward — a different level of engagement, commitment, and freedom to be flexible.

But I wanted very much to create an atmosphere — in a way the book is not plot-driven but mood-driven. I wanted to create the claustrophobia that he feels in a place which has small, dingy rooms. He doesn’t want to be there, and I want you to feel his discomfort and his self-loathing. Maybe I should, but I don’t have a dislike of myself in the way that he does (laughs). Through the course of this novel, there is a real feeling that he’s lashing out in frustration that his whole life has been a waste of time. And I think there’s something very poignant about that. Even if we don’t feel that ourselves, I think we can all relate to how it must feel to get to late middle-age and feel that everything you’ve based your life on, you’re not sure that it’s true.

JH: Coming back to music, and the concert this Saturday — in another interview, you talked about the “youthful” and “thrilling” qualities you see in Mendelssohn’s First Concerto, and how you feel “completely invigorated” playing it. You also feel that Mendelssohn’s music is not performed enough in general.

SH: I think Mendelssohn’s one of the great geniuses. He’s undersung for all sorts of reasons. And this concerto is incredibly fresh to me. If you asked for three words to describe this piece, ‘fresh’ would be one, ‘brilliant’ would be another, and I think there’s an affection to the piece too. It’s not pretentious, it has a real joyful spirit in the last movement — completely exuberant. And yet you also get this turbulence, which is there in so much Mendelssohn.

When I was recording all of his music for piano and orchestra, I kept noticing con fuoco in the score. I went through and counted, and I think there are fourteen con fuoco’s in those piano concertos. It’s a very characteristic flavor of Mendelssohn, this fiery spirit. And I think one of the problems is that people sometimes think of Mendelssohn — maybe because of the Songs Without Words — as sort of wishy-washy. They don’t always think of that fuoco that’s at the center of everything he wrote.

The concerto is also fantastically concise. It’s just a little over twenty minutes, and yet you feel that you’ve been through a very satisfying meal. He never overstates things. Second-rate composers often have wonderful ideas, but they don’t know how to develop them, or they just repeat them too many times. You never feel that with Mendelssohn.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com August 14, 2018.

Click here for a printable copy of this article