by Jarrett Hoffman

The pianist is Xak Bjerken, whose greatest talent is perhaps his balancing act. Every note is infused with expression, yet his individuality never spills over to eclipse the compositional voices of Stephen Hartke, Elizabeth Ogonek, and Jesse Jones. Those same words could just as easily describe conductor Timothy Weiss, who leads the Oberlin Contemporary Music Ensemble with the ultimate combination of precision, musicality, and musical vision.

The disc begins with ecstatic energy: a brass glissando and a galloping keyboard part to open Hartke’s Ship of State for piano and an ensemble of twenty. There are many standout moments, including that one, throughout the four sections of this single-movement concerto. But the bigger picture is that Hartke has created a musical world so convincing that events seem to take place of their own volition, without any sense of a creator imposing their will.

As is the case with each concerto on the album, Ship of State is very much a dialogue in which Bjerken takes turns engaging with different sections and soloists within the group. The interplay is brilliant, and the material is often quite difficult, but nothing sounds like a struggle for Bjerken — the owner of ten agile and sensitive fingers — or for the Contemporary Music Ensemble, which shines in every way.

Ogonek, who moved on to the faculty of Cornell University in the summer of 2021, goes in a decidedly different direction with where are we now. Scored for piano, four percussionists, and six male voices — who sing a text written for the piece by Paul Griffiths — the seven-movement concerto is highly influenced by Medieval and Renaissance music.

Mesmerizing if a little slow to evolve at times, the concerto intrigues with its wide spectrum of harmonies — from Renaissance purity to biting dissonance — and its alluring soundscape full of inventive use of percussion. Bjerken highlights another virtue of the piece, channeling a distinctly smooth and poetic style that fits the music like a glove.

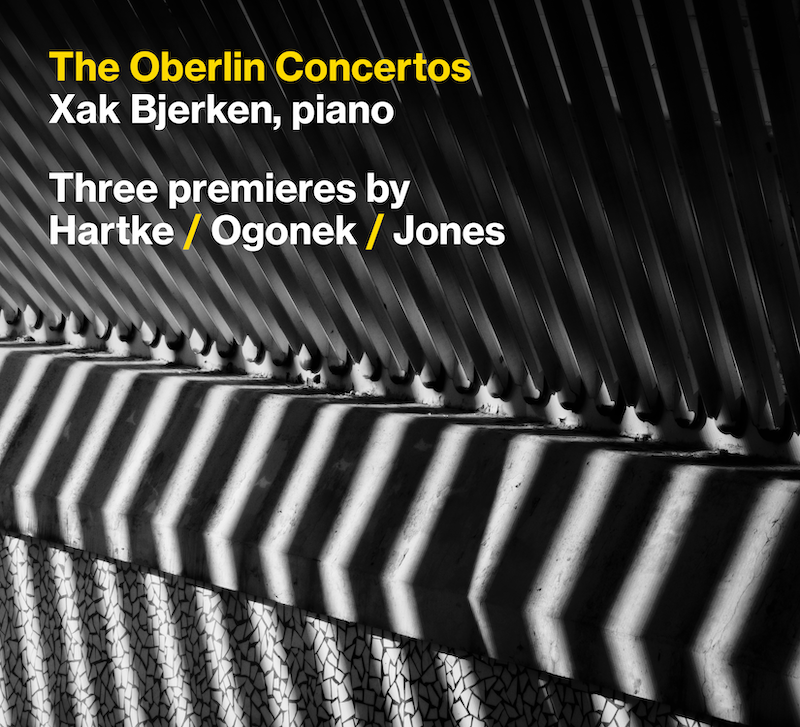

The album closes with the piece that started it all: Jones wrote PERSONA MECHANICA for Bjerken (pictured), his friend and former teacher, and that commission led to the other two. In fact, the theme of Jones giving life to music continues in this concerto for piano and chamber orchestra, which envisions the keyboard coming alive.

You can hear that clearly in the gradual, halting motion of the opening, as more and more energy begins to course through the writing. Perhaps in the second movement, “Dolente” — where Bjerken mines the depths of emotional pain — the instrument discovers the downsides of consciousness.

On the purely musical side, Jones possesses a thoroughly original voice, and has a knack for conjuring up surprising yet subtle sounds. Some shuffling sandpaper blocks here, to make you tilt your head. A wind instrument hidden among the strings there for a slight shimmer in the sound, drawing you in. And thanks to the ensemble’s excellent balance, these little spices are just that, making them all the more satisfying.

The finale keeps you on your toes, its engaging rhythms filled with pods of silence. And the conclusion will surely make you smile. With a rapid run up the keyboard, a colorful whack on the vibraslap, and a punchy, playful last chord, it brings to mind a famous phrase: “That’s all, folks!”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com January 12, 2022.

Click here for a printable copy of this article