by Daniel Hautzinger

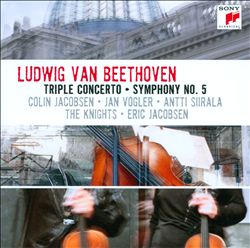

That congenial spirit fits the highly collaborative Triple Concerto well. Knights violinist Colin Jacobsen, cellist Jan Vogler, and pianist Antti Siirala share the limelight as soloists, relishing the musical back-and-forth (Jacobsen is also a member of Brooklyn Rider with Knights conductor Eric Jacobsen). The cello often leads, which is good news when it’s played by Vogler. He has one of the more astonishing tones of any cellist: impossibly expressive, whether potent or dulcet. This is in contrast to Jacobsen, whose sound is pared down and razor-like, especially in the upper range. Siirala’s clear, smooth touch infuses each note with effervescence.

But the Triple Concerto is more about interaction than the individual, and these three, who met playing chamber music, clearly delight in performing with each other. The best passages occur when their lines intertwine and converse, as in the delectable call-and-response during the first movement where the piano doubles the violin in the right hand while bantering with the cello in the bass. The Knights realize this and support the soloists’ dialogues with minimal interruption, providing a wide cushion in the second movement and acting as energetic pistons in the last. The finale is the apex of the work; virtuoso flourishes flash between soloists in an exhilarating display of conviviality.

Then the soloists depart and allow the Knights to exhibit their bonhomie alone in a strange performance of the Fifth Symphony, again conducted by Eric Jacobsen. This is a distinctive Fifth. The strings play mostly without vibrato and the orchestra is small, to presumably better encourage camaraderie. It could almost be a period instrument performance. There is a thin grittiness, especially in the first movement, that causes the famous opening to sound like a parody, a synthesizer with a dramatic “orchestra hit” patch rather than real instruments. Trumpet accents in the relentlessly fast first movement could be mistaken for sirens with their uneasy intonation. It seems like the Knights purposely added some roughness to revitalize the work and recreate what it may have sounded like at its premiere.

The rest of the piece is more successful. The Knights’ belief in the power of this music is evident, especially in the uplifting second movement. They play the whole symphony with the foreknowledge of its triumphant ending, so that the dark scherzo slyly winks rather than foretells doom. The scherzo’s trio surges forth, driving impatiently to the victory that is in sight. And that victory is glorious when it comes in the finale, though it is slightly undermined by an absurdly long echo during the last measures, as if the orchestra were suddenly recording in a cavern. (This odd recording choice mars the end of almost every track).

Whatever your opinions of the Knights, they certainly are true to their mission statement of companionability and new approaches. They sound delighted to play together and give a fresh take on old music, so who cares if it’s not everyone’s cup of tea?

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 22, 2014

Click here for a printable version of this article.