by Daniel Hathaway

Several generations of composers over the centuries have heralded their experiments as “modern” music, from the Ars Nova to the Secunda Prattica, to the post-Romantic, but on Wednesday evening, “modernism” meant the turning away from tonality and its harmonic implications toward new systems based more on intellectual constructs than emotional content.

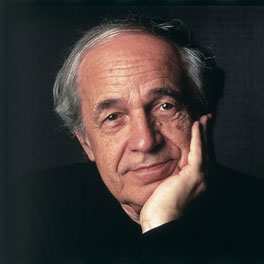

Boulez’s own Sonatine for Flute and Piano from 1946 is such a heady exercise, written using the twelve-tone system in which a row made up of all the notes in the chromatic scale is organized, then used in various forms (retrograde, inversion, and retrograde inversion) to create the content of a piece. Boulez wrote three such works before turning his back on the method, considering it constricting and academic.

The Sonatine formed the centerpiece of Wednesday’s playlist, curated by pianist Shuai Wang and flutist Madeline Lucas Tolliver, who performed the thorny 13-minute work with admirable savoir faire. In the printed program, the flutist paraphrased Boulez’s own description of the piece (“organized delirium”) as “cultivated chaos,” and that’s certainly how it comes across. It would take many hearings to discern what connects the material the two performers are playing.

Earlier, Lucas Tolliver and Wang joined clarinetist Benjamin Chen, violist Eric Wong, and cellist Daniel Pereira in Improvisé — pour le Dr. Kalmus, Boulez’s little 80th birthday tribute to the head of the London office of Universal Edition, and a piece the composer later revised to celebrate his own entry into the ninth decade. Doubtless highly organized, it sounded crystalline but no less chaotic on first hearing.

To begin the evening, Lucas Tolliver and Wang gave an arresting account of Olivier Messiaen’s Le Merle Noir (The Blackbird), written in 1951 as a test piece for the Paris Conservatory. Alternating periods of repose and frenzy were separated by expressive caesuras.

Wang turned from piano to harpsichord for Gyorgy Ligeti’s tendonitis-inspiring Continuum from 1968, a non-stop toccata of minimalist cells that changed and expanded in nearly imperceptible increments. Ligeti’s music proved as captivating and challenging as it always does, and Wang brought the piece off with precision and flair.

Violinist Yun-Ting Lee joined Pereira for John Cage’s Sonata for Two Voices, a 1933 work that uses a cryptic system of 25 pitches to create a Sonata, a Fugato, and a Rondo, played on Wednesday with energy and charm.

To end the program, Pablo Devigo conducted the entire ensemble, now joined by percussionist Thomas Sherwood, in Mario Davidovsky’s Flashbacks (1995), described by Wang in her notes as “a musical fantasy attempting to make an intelligible musical narrative out of an apparently chaotic landscape.” (“Chaos” again!)

Davidovsky’s work proved to be the most attractive and accessible piece on the program. It was certainly the most fun to watch — most eyes were glued on Sherwood, who moved with the grace of a dancer among a plethora of percussion instruments, striking a note here, bowing a gong there, and seemingly never missing a cue.

The hour’s worth of music on the program stretched out into a 90-minute affair due to stage choreography and an intermission. It seemed a bit fussy to roll the piano offstage, roll the harpsichord on, then reverse the process.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com November 10, 2016.

Click here for a printable copy of this article