by Daniel Hathaway

On Tuesday, violinists Edward Dusinberre and Károly Schranz, violist Geraldine Walther, and cellist András Fejér will play the quartets in B-flat, Op. 18, No. 6, in F, Op. 135, and in C, Op. 59, No. 3, the “Razumovsky,” arranged not in chronological order, but in an uplifting spiral of rising fifths from B-flat to F, to C.

It’s common knowledge that Beethoven turned music on its ear during his creatively eventful career, but it’s worthwhile reminding ourselves from time to time exactly how he changed the course of musical composition and performance.

In his excellent 2008 lecture on the Greshman College series in London, Professor Roger Parker said,

Beethoven’s most famous works were powerfully implicated in enormous changes in the ways music was performed, listened to and written about. Let me list a few of these changes: the decisive emergence of silent, attentive listening; the parallel emergence of instrumental music as more serious than vocal music; an increasing sense that a certain strand of this instrumental music, now commonly called ‘classical music,’ was spiritually uplifting and morally superior; a new hierarchy between the composer and the performer, one that saw the latter as merely a vehicle to express the thoughts of the former; an increased attention to, and reverence for, the score as a repository of the ‘work’; and so on and on. Does all this sound familiar? It should do, because it marks the decisive emergence of ‘our’ classical musical world, with its concert going, its silent listening, and all the rest; a world that probably saw its peak in the statesponsored 1950s and 1960s, and that is now, most would admit, in slow decline.

The idea that Beethoven’s works required “silent, attentive listening” separates them from earlier chamber music and requires more active participation on the part of the listener. As Professor Parker said elsewhere in his Gresham College lecture,

…an early review of the Op. 59 quartets…admitted that they were ‘long and difficult’ but followed this by saying that ‘admirers hope that they will soon be engraved’. The message is plain: these works are complicated for a reason; they are not entertainment; we need to study them in order to understand them.

There are many ways to “prep” for a performance of Beethoven quartets. Of course, you can just show up early and take in the printed program notes (usually supplied these days for the Cleveland Chamber Music Society by the excellent Peter Laki). You can show up even earlier — at 6:30 pm next Tuesday — to hear Eric Kisch’s take on the program in a pre-concert lecture. But for those who would like to be even a little more on top of the experience, here are a few ways to do your homework on each quartet before Tuesday’s performance.

Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 18, No. 6

- The Ensemble Society of Indianapolis provided an engaging introduction to Beethoven’s early quartets — and this one in particular — in its notes to a performance by the Takács Quartet in April of 2010.

- A live (and lively!) performance of the work by the Amphion String Quartet on New York’s WQXR during its Beethoven String Quartet Marathon on November 18, 2012, is available on YouTube.

- If you’d like to follow along with the score, you can view it onscreen or download the music (18 pages) from the IMSLP/Petrucci Music Library, a terrific online resource for public domain scores. It’s free, but you can join for a modest fee and avoid waiting a few seconds for the download.

Quartet in F, Op. 135

- A performance of Beethoven’s last quartet on YouTube by the Alban Berg Quartet comes along with an onscreen score.

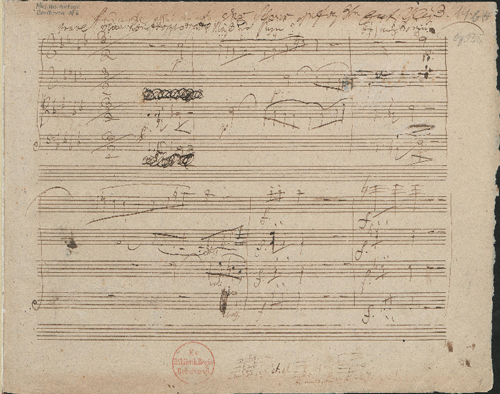

- If you’d like to see what music publishers and scholars are up against when trying to decode Beethoven’s famously obscure handwriting, IMSLP-Petrucci offers a pdf file of the fourth movement of his autograph score. Good luck following along with that!

- And a fine set of notes by John Mangum for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, considers the meaning of Beethoven’s mysterious “Muss es sein?” (Must it be?) annotation in the slow introduction to the finale.

Quartet in C, Op. 59, No. 3 “Razumovsky.”

For background on the third of the “Razumovsky” quartets, I’ll send you back to Professor Roger Parker’s Gresham lecture, illustrated by the Badke Quartet. If you follow the link, you can read his remarks onscreen, hear audio of the 55-minute lecture, and download a transcript. (While you’re on that site, have a look at the other lectures in the Gresham College series, which might send you down a fascinating rabbit-hole.)

Published on ClevelandClassical.com April 13, 2017.

Click here for a printable copy of this article