by Jarrett Hoffman

The program includes Harrison’s Concerto for Piano with Javanese Gamelan and his Suite for Violin with American Gamelan, and will feature pianist Sarah Cahill, violinist David Bowlin, and the Boston-based group Gamelan Galak Tika, directed by Evan Ziporyn, playing two of the composer’s own sets of gamelans.

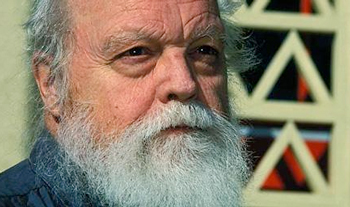

Composer and clarinetist Evan Ziporyn makes music at the crossroads between genres and cultures. After discovering the gamelan while working at a record store in college, he made his first trip to Bali in 1981, returning on a Fulbright six years later. A co-founder of the Bang on a Can All-Stars, his compositions have been commissioned by such groups as the Silk Road Ensemble and Kronos Quartet. As a clarinetist, he shared a Grammy Award in 1998 for his recording of Steve Reich’s New York Counterpoint. He teaches music at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In a recent phone conversation, Ziporyn began by sharing thoughts on his relationship with Lou Harrison’s music.

Evan Ziporyn: When I was younger, I was interested in gamelan, working with non-Western musicians and traditions, and really getting inside of them in as deep a way as I could. But somehow it never occurred to me that he could provide guidance either through his work or in his person — even though we were both out on the West Coast, and he was already an older composer and I was just a graduate student. It was only after I moved back east that I started paying attention to his music.

I’ve been turning students on to his music for twenty years now. But what’s new is getting this actively involved with his music. As his centennial came up, I realized the gamelans were in Boston and nobody was doing much with them here, and the Piano Concerto is an amazing piece that’s rarely heard because you need to have those instruments to play it. I thought, ‘We should do this.’ So we’re doing it.

Jarrett Hoffman: You and Harrison have similar paths, but your music also sounds completely different.

EZ: In Lou’s mature music, there’s a serenity and a sense of being comfortable with who he is and with what he regards as beautiful, noble, and coherent. There’s no apology — it’s kind of in a world of its own. But it wasn’t always that way. He had to struggle very hard artistically and personally to get to that point, and there’s a lot of very good music he wrote along the way where you can feel that.

I think my compositions — definitely in my 30s and 40s, maybe not so much now — are less about struggle and more about embracing the contradictions that come with making music in a busy world. I liked that. I think it was a sort of generative force for some of the energy in my music. Particularly when there’s a cross-cultural linkage, I’ve always wanted to deal with the ways that can be complex and thorny.

JH: Tell me about the instruments that will be used in the performance.

EZ: The gamelans are owned by Jody Diamond, who was a friend and artistic collaborator of Lou’s. He and his partner William Colvig built both sets, unique in their own ways. For the Concerto, the piano has to be tuned in this very complicated way to fit with the gamelan, so in that sense even the piano is Lou’s.

JH: You took Gamelan Galak Tika on tour to Bali in 2005. After having been introduced to that country yourself, what was it like to be introducing it to other people?

EZ: It felt really good, like a full circle. Most members had never been to Bali and had only experienced the culture through the music, so it was great to be able to bring a bunch of people I felt close to into that world.

JH: I read that the group includes students, staff, and community of MIT.

EZ: Yes, and actually the Boston area at large — we’re basically open to anybody. It’s part of the MIT music program, but we try to keep to the gamelan ethos: if you’re willing to show up and do the work, you can be in the group. One of the great things about gamelan in general is that it’s designed to accommodate different skill levels and experience in a meaningful way. Whether you have killer technique and are really quick with learning the patterns, or you’re devoted to the music but don’t have much technique, there are essential parts you can play.

Aside from the cultural and purely musical aspects, one of the things I really like about gamelan is that it’s a way to perform at a high level with people you might not normally encounter in music. We have professional musicians and advanced music students, but we also have people who literally have walked in off the street and never made music in an organized way before joining the group.

JH: Your father, a violinist, played a big part in you becoming a professional musician. How did you approach raising your kids with music?

EZ: When my son decided he wanted to get serious about an instrument, I told him, look, you can play any instrument you want, but please don’t play the oboe. You’ll just spend your whole life making reeds and be really unhappy. He plays the oboe — and that’s all I have to say about that.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 17, 2017.

Click here for a printable copy of this article