by Mike Telin

The Cunning Little Vixen: dress rehearsal (Roger Mastroianni)

With its made-for-Cleveland production of Janáček’s The Cunning Little Vixen featuring state-of-the-art digital animation, The Cleveland Orchestra finds itself once again at the cutting edge of opera technology. Once again? A visit to the Cleveland Orchestra archives reveals some fascinating information about technological innovations that can be traced back to the opening of Severance Hall on February 5, 1931.

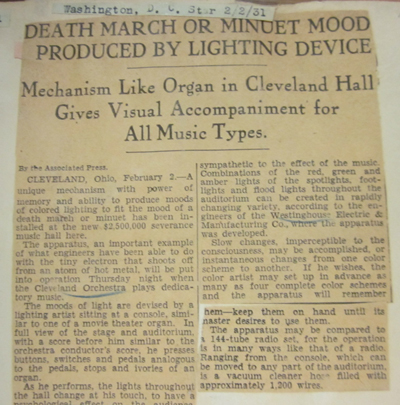

An Associated Press preview published in the Washington D.C. Star carried the headline, “Death March or Minuet Mood Produced by Lighting Device: Mechanism Like Organ in Cleveland Hall Gives Visual Accompaniment for All Music Types”. The article continued,

“The apparatus, an important example of what engineers have been able to do with the tiny electron that shoots off from an atom of hot metal, will be put into operation Thursday night when the Cleveland Orchestra plays dedicatory music.

“The moods of light are devised by a lighting artist sitting at a console similar to one of a movie theatre organ… As he performs, the lights throughout the hall change at his touch, to have a psychological effect on the audience sympathetic to the effect of the music. Combinations of the red, green and amber lights of the spotlights, footlights and flood lights throughout the auditorium can be created in rapidly changing variety, according to the engineers of the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co., where the apparatus was developed.”

The Clavilux or Color Organ (Cleveland Orchestra Archives)

The lighting innovations made an impression on the Plain Dealer’s William F. McDermont, who wrote in his opening night report,

“The lighting system was the one feature of the hall most surely unique, the feature that contributed most largely to the effect of the fluidity and variety and the peculiar transparent richness of the main auditorium. This lighting arrangement will add immensely to the effectiveness of future symphony programs. In combination with dancing it will make possible an association of music and spectacle with an effect of splendor and variety hitherto unknown.

“Severance Hall represent the first complete use that music has made of the tremendous development in recent years of the possibilities of lighting, so shrewdly and so well used on the stage by Florenz Ziegfeld and David Belasco.

“The lighting plant at Severance Hall must be at the moment the most modern and complete of any in the world, and Thursday’s audience got a faint idea of its remarkable resources and ingenuity.”

The Severance Hall lighting system and its command center, the Clavilux or color organ, was big news to the electrical engineering community as well, inspiring a highly technical article in Electric World on March 7, 1931.

Other state-of-the-art features of the hall included the two lifts and the stage curtain. Reporting in its April 25, 1931 edition on a program led by Nikolai Sokoloff that included dance, Musical America wrote,

“The programs utilized the modern equipment of the stage at Severance Hall, particularly the two lifts, whereby the orchestra plays in a pit below the level of the stage, out of sight of the audience. The stage production also made use of flexible colored illumination and gained an illusion of space by means of a curved “sky dome.” The dancers appeared to the audience against a background of varying color and apparently great distance, as they moved on modernistic structures especially designed for these productions.”

Washington D.C. Star Clipping (Cleveland Orchestra Archives)

The curtain attracted attention as far away as Oklahoma. On March 1, 1931, the Oklahoma Tribune reported,

“The new $2,500,000 Severance Hall, home of the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra here, contains a stage curtain which is one of only three in the world. It is electrically operated, and it is possible to obtain 36 different designs in raising and lowering it.”

Not everyone was so enthusiastic about all the new gear, one important detractor being the music director. About the lighting system, Nikolai Sokoloff wrote

“[The Clavilux] was the most ghastly thing imaginable, throwing a red light on us when we played Brahms, a blue light when we played Debussy, and so on. A third rate movie house couldn’t have devised a more vulgar effect.” —Donald Rosenberg, The Cleveland Orchestra Story.

Although the new technology may not have been so compatible with orchestral concerts, it would be in opera that new lighting effects would prove most successful. With the onset of the Great Depression, when New York’s Metropolitan Opera eliminated Cleveland as a stop on its national tours, The Cleveland Orchestra stepped into the vacuum and began producing its own operas under its second music director. Artur Rodzinski’s 1933 production of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde was the first fully-staged opera to be produced in Severance Hall, as well as the first to take profit of the new stage and lighting technology.

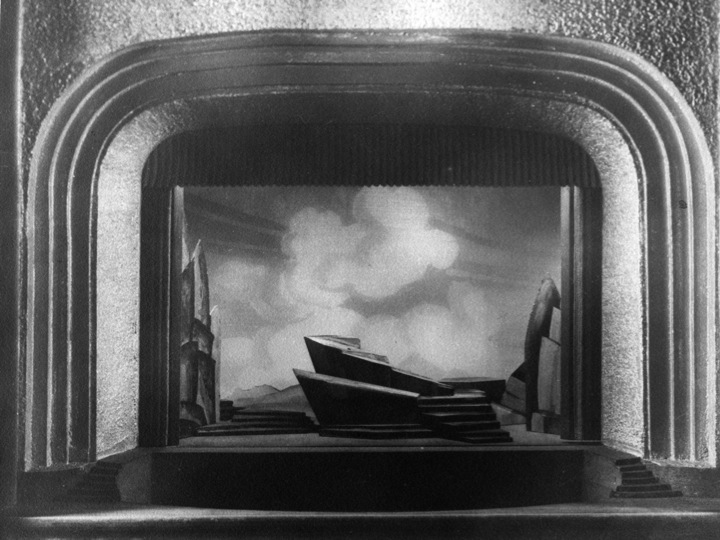

Set for Tristan und Isolde, 1933, designed by Fredric McConnell (Cleveland Orchestra Archives)

The production was announced in October and the opera opened on November 30. A Cleveland Press preview ran on November 27 with the headline, “Tristan and Isolde at Severance Hall: Introducing new lighting effects.”

“Fredric McConnell, director of the Play House, and Max Eisenstat, technical director, well known to Cleveland audiences for the excellence of their lighting effects in Play House productions, have been called in to design the settings and arrange the lighting for Artur Rodzinski’s production of the famous opera. There will be no old-fashion scenery of the sort usually used with operatic performances. Instead, Mr. McConnell says, the stage setting will consist of a “broken series of plastic forms.” He goes on to explain: ‘Plastic forms which themselves make a simple and harmonious stage picture will be used. The idea behind the design is to place singers and the music in bold relief against a pleasing background. A simple design is being used purposely to put the emphasis on the music.’

“The lighting effect will be controlled through the Severance Hall ‘color organ,’ a console not unlike that of an organ. Each key, however, instead of controlling an organ pipe, controls an elaborate arrangement of vacuum tubes which in turn automatically control the light switches. With the aid of this color organ, the system of lighting known as ‘zone lighting,’ will be used in this system, various parts or zones of the stage are thrown into prominence by changes in the lights as the action of stage changes and emphasis shifts from one place to another. The stage at Severance Hall has a great plaster backwall known as a “sky dome.” Much of the lighting will be accomplished through diffused lights upon this. The lights will be used at all times to intensify and heighten the effect of the music.”

The production won raves from audiences and critics. A review in Musical America on December 10, 1933 ran under an elaborate series of headlines: “Tristan und Isolde is triumphant success under orchestra’s auspices — draws three capacity houses and wins high praise for conductor — excellent staging in Severance Hall by McConnell — effective lighting adds to glamor of production.”

Macquette for Die Walküre, designed by Richard Rychtarik, 1934 (Cleveland Orchestra Archives)

Tristan und Isolde marked the first of fifteen fully-staged operas conducted by Rodzinski at Severance Hall between 1933 and 1938. After the disruptions of World War II and the reconfiguring of the stage by George Szell, fully-staged opera finally returned to Severance Hall in 2009 following its millennial restoration, when the orchestra pit was restored and the “Szell Shell” was removed. In 2009, music director Franz Welser-Möst launched the modern era of opera at Severance Hall by remounting Zürich Opera productions of Mozart and DaPonte’s The Marriage of Figaro, Così fan tutte (2010), and Don Giovanni (2011).

Set for Così fan tutte, 2010 (Cleveland Orchestra Archives)

The Zürich productions, which featured minimalist stage settings enhanced by lighting and special effects, represented a modernist approach to staging that was already present in Richard Rychtarick’s designs for 14 of the 15 operas produced in the 1930s.

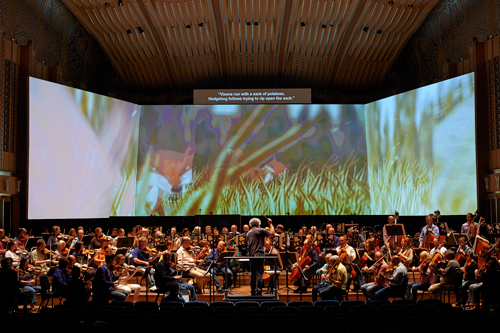

On Saturday evening, when The Cleveland Orchestra premieres its four-performance production of Leos Janacek’s The Cunning Little Vixen, the tradition of modernism combined with cutting-edge technology will continue at Severance Hall. In this case the technology involves digital animation.

Director Yuval Sharon said that when he was first approached about designing the production he had already had the idea of engaging singers in animation. Franz Welser-Möst embraced the idea as a way of solving some of the big performance challenges of the opera.

Ironically, though the process of developing a 90-minute animation closely keyed to the score and staging would involve very sophisticated technology, Bill Barmanski of Robot Studio began his work just as designers did in the 1930’s — by constructing cardboard sets using scissors and glue. His colleague Christopher Louie showed in a production diary video how the team built used lights to play with shadows and built cardboard trees for the forest scenes, after which they photographed the models and blew them up to a hundred times their actual size. (View the two production diaries here and here.)

The Cunning Little Vixen Dress Rehearsal (Photo: Roger Mastroianni)

Judging from the sneak preview provided by Thursday evening’s dress rehearsal, the synthesis of real and artificial worlds in The Cunning Little Vixen represents a new chapter in the innovative use of technology at Severance Hall.

Daniel Hathaway contributed to this article

Photos courtesy of the Cleveland Orchestra Archives (Deborah Hefling, archivist) and The Cleveland Orchestra (Roger Mastroianni, photographer).

Published on ClevelandClassical.com May 16, 2014.

Click here for a printable copy of this article.