Daniel Hathaway | Cleveland Classical

CLEVELAND, Ohio — The four Cleveland Orchestra concerts at Severance Music Center this weekend are as traditional in form as orchestral programs can be. Although they follow the long-established formula of Overture – Concerto – Symphony and feature standard works by Beethoven, Haydn, and Beethoven again, the interpretation of those pieces on Thursday evening was anything but business as usual.

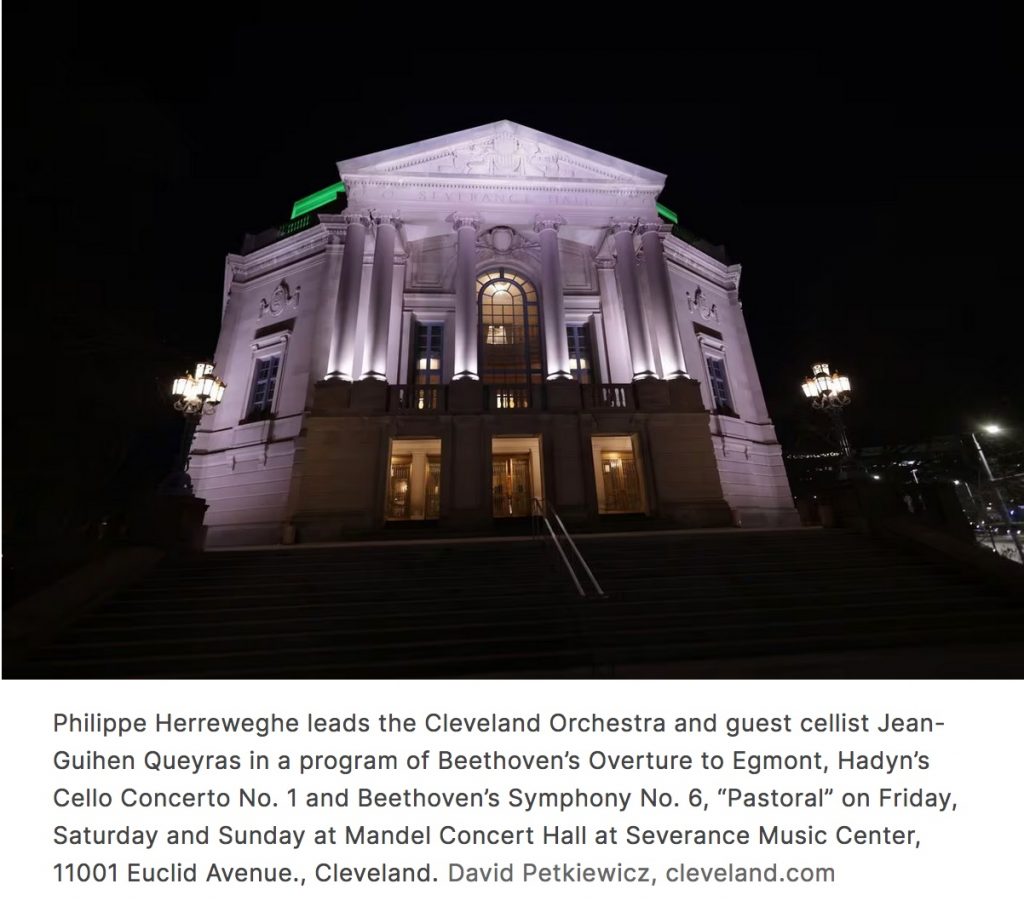

Making their Cleveland Orchestra debuts in this “Beethoven’s Pastoral” program on Thursday, guest conductor Philippe Herreweghe and cello soloist Jean-Guihen Queyras brought historical sensibility and a deep knowledge of the scores to their tasks. Performing to a large crowd, Herreweghe, Queyras, and the orchestra made sure that every note and phrase leapt off the page and into the ear with freshness and immediacy.

The Belgian guest conductor signaled a departure from the norm by carrying his own score to the podium. Conducting without a baton, he called for a regal opening to the Egmont Overture. The orchestra responded with a full, burnished sound despite the reduced string section, which otherwise produced a litheness that contrasted with the Overture’s bold character. Introducing its triumphal ending, Herreweghe encouraged the four hornists to play out, sounding like brassy, natural horns.

Frequently under-rated as a transitional piece between Baroque and Classical concertos, Haydn’s first cello concerto gained weight and significance in the hands of Jean-Guihen Queyras, who truly owned the piece on Thursday evening with a magisterial reading that made perfect sense.

Performing without an endpin, Queyras played along with his colleagues on the bass line before launching into the opening lines of the solo part. His melodic passages were pure beauty and he played thorny, technical lines with ease, producing a tone that projected easily into the hall. A delightfully humorous return to the opening theme led to an inventive cadenza.

The wind players put down their instruments for the second movement, when the solo cello sang out with a smooth, lovely tone and a not overly mannered operatic quality. Herreweghe launched the finale with a brisk tempo that never lost momentum or prevented the orchestra from clearly articulating its parts.

Queyras’ playing was light-footed, as he insouciantly tossed off scale passages. The coordination between podium, soloist, and orchestra produced magnificent results. The large audience obviously knew they were in the midst of something very special and rose quickly to their feet after the concluding bar for a well-deserved ovation.

As an encore, the cellist offered a short Ukrainian folk melody which led directly into a ravishing performance of the Prelude from J.S Bach’s Solo Cello Suite No. 1.

The concert ended with Beethoven’s only programmatic Symphony, which marked a departure from earlier works in music history. Rather than trying to depict nature, Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony attempts to convey the feelings of a rambler like the composer when he arrives in the country.

Herreweghe and the orchestra crafted a serene, pastoral opening with transparent textures and unforced lines that were allowed to breathe and expand. Winds added plausible bird calls, as they did in imitating a cuckoo at the end of the second movement’s beautiful scene by a babbling brook.

The delightful scherzo with its charming dance tune played by oboist Frank Rosenwein soon gave way to a galumphing, rustic peasant dance, then the horns majestically signaled the brewing of a storm — a brief tempest that sent everyone indoors.

As the sun came out again, the symphony concluded with a calm hymn of thanksgiving — a perfect pastoral ending that the composer obviously hated to bring to a conclusion. If Beethoven had heard this wonderful performance, he might have extended the piece even further.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com. February 26, 2024

Click here for a printable copy of this article