by Peter Feher

The infamous soundtrack to secretary Marion Crane’s final moments in the shower — and also to private investigator Milton Arbogast’s stumbling death down the stairs later in the film — is horrifyingly simple. A series of screeching down-bows begins in the first violins and then stacks in dissonant intervals as the remaining string sections join in. The gesture is more like a Foley effect than music per se, evoking something between a human scream and the shriek of metal against metal.

It was maybe inevitable that the sonic illusion would be broken in The Cleveland Orchestra’s performance of Herrmann’s score on Wednesday, Nov. 5, at Severance Music Center. The ensemble can’t help but sound supremely polished, whether playing a Mozart symphony or accompanying a film in concert.

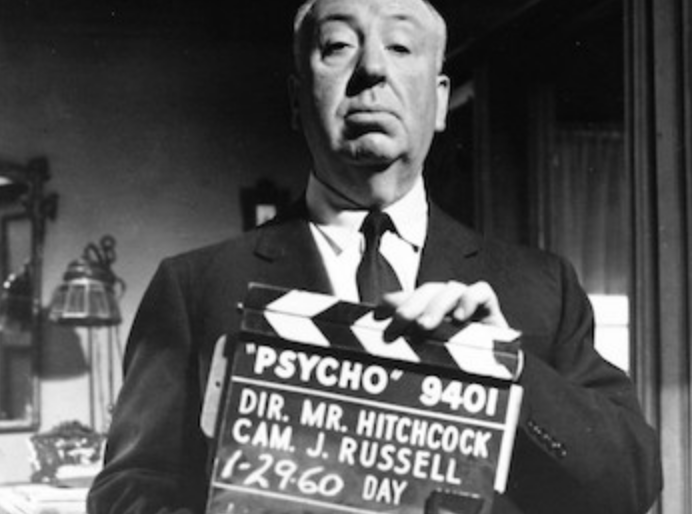

Some of the raw shock of Psycho may have been missing in this showing — though it should be said that Hitchcock’s study in suspense has already been partially spoiled for modern audiences who know what’s coming in the shower scene. Still, experiencing the film with live orchestra was an opportunity to appreciate the stark materials that can combine to create a masterpiece.

Many of the movie’s initial artistic decisions were a matter of limited means. Hollywood producers, not sold on the violent story, denied Hitchcock his usual funding, so the director financed the film himself and shot it in black and white (cheaper than color). Herrmann likewise had a restricted budget and settled on the reduced personnel of a string orchestra, whose muted sonorities would perfectly match the visual palette.

Money turned out to be something of a MacGuffin, which everyone involved in the production must have suspected. After all, the plot of Psycho starts with Marion stealing $40,000 but devolves into the much stranger story of motel owner Norman Bates — to the extent that the original theft is essentially forgotten.

The movie was a commercial and creative success for Hitchcock and his collaborators, not least Herrmann, whose approach to scoring as sound design would become the standard for subsequent generations of film composers.

Herrmann does provide one proper theme — shot through with plenty of anxiety and pulsating rhythms — which is heard during the opening credits, as well as in several tense psychological sequences early on. The Cleveland Orchestra dispatched this music with taut precision under the baton of guest conductor Joshua Gersen.

The string writing otherwise stays in the background, setting each scene subliminally and drawing little attention to itself. In the movie’s first 30 minutes, the mood goes from sultry to sinister, thanks in large part to the subtle transformation of the same two or three musical cues.

If the shower scene no longer jumps out as the surprise that Hitchcock intended (he initially thought the moment would be most effective without any music whatsoever), viewers can still be startled by the stroke of genius that Herrmann contributed.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com on November 13

Click here for a printable copy of this article