by Daniel Hathaway

Organist Clark Wilson is one of the most prominent scorers of silent photoplays in America today. His accompaniments reflect the techniques and materials of the musical performances given in major picture palaces during the heyday of silent film.

One of those resources is the theater organ, which represents a special tributary in the grand stream of pipe organ history, and was only made possible by developments in electricity around the turn of the 20th century.

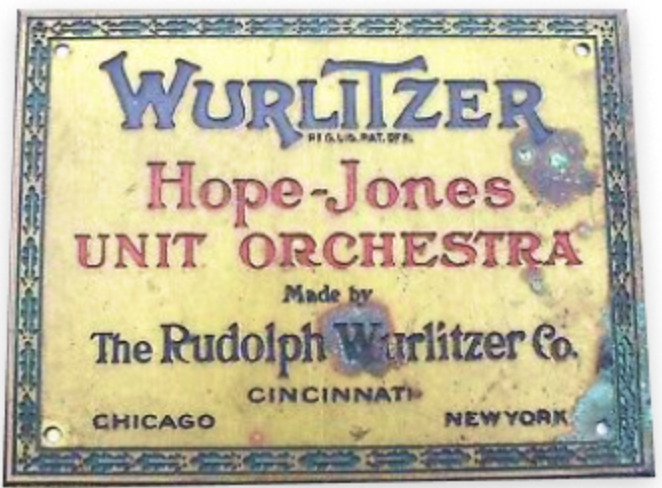

Before that time, the liaison between player and pipes was mechanical. Once inventors like Robert Hope-Jones in Britain discovered how to open valves to let air into pipework electrically, entirely new possibilities arose. That led to inventions like the Hope-Jones Unit Orchestra, which comprised a small number of ranks whose individual pipes could be wired in at different pitches on different keyboards.

According to the Western Reserve Theater Organ Society website, “The tonal sounds of the theater organ were designed specifically to provide more robust and engaging music to match the action and storyline of the silent film. Theater organs also included tuned percussion such as glockenspiels, xylophones, or chimes and untuned percussive sounds such as drums, train whistles, and car horns to further match the on-screen action.”

Wurlitzer’s Opus 793, the instrument Clark Wilson will play on September 6, was originally installed in the Granada Theatre in Santa Barbara, California in February 1924 where it was used until the 1950s. It came to Cleveland via a residence in Pasadena, then was stored in Brighton, Michigan from 1996 to 2006, until its owner gave it to the Western Reserve Theater Organ Society.

Volunteers donated more than 6,000 hours and $110,000 in construction, repairs, re-leathering, and upgrades to the project, and the instrument, now comprising 28 ranks of pipes, tuned percussion stops, traps, and a “toy counter” (untuned percussion and sound effects) was inaugurated in November of 2011.

Clark Wilson’s travel schedule made an interview unfeasible, but the organist graciously agreed to respond to some questions via email.

Daniel Hathaway: What musical materials will you be working from for the Harold Lloyd screening? How much of the underscore will be your own?

Clark Wilson: There are few, if any, of the cue sheets left from Lloyd pictures. Therefore, you create your own and in this particular case it’s an abbreviated cue sheet. (There’s no way you’re going to read a bunch of pages of full music for something like this and even remotely hope to keep with the action. It’s also extremely risky to count on inspired improvisation for an entire evening’s performance.)

The style at the time for comedic work relied on much popular music, as well as bits from the established classics, and this “backbone” is linked together by some careful improvisation (as opposed to improvising an entire score, which was quite frowned on and not done if one had any respect for his business).

Think of Carl Stalling’s exemplary work in scoring the Warner Brothers cartoons. And why not, as he was first a theater organist. It’s of paramount importance to stick with period music if we’re giving a genuine historic experience and presenting what audiences heard and saw when the films were new. It’s so very important to not use progressive jazz, rhythms unknown in the ‘20s, bang on brake drums, play Bach, or call attention to ourselves if we are being true to the artform.

As the organists of the time did, I pull together as many as 50 themes, then vary those as necessary to fit the mood and action. The important thing is that there is REAL MUSIC used, as opposed to mindless wandering for long stretches. Much of this was emphasized heavily in print and in practice in the ‘20s by the top picture people in the country. Always on your mind is the fact that the organist is the voice of the film — and at one time was the actual extended scoring wing of Hollywood. What one did at the console was important and was carefully watched in the big picture palaces.

DH: Are there special opportunities or challenges involved in playing for a comedy?

CW: One can certainly never take his eyes off the screen, because things happen at a rollercoaster rate, and action or a direct cue (which might involve sound effects) can be missed. The comedies might be said to be more challenging because of the speed and lack of chances to really develop musical themes. On the other hand, they can be a tremendous amount of fun to play and are universally loved by general audiences which, in turn, feeds electricity back into one’s performance.

DH: Safety Last! has been described as an edge-of-your-seat film. How do you keep that excitement going musically for over an hour?

CW: The edge-of-the-seat aspect, of course, involves the climbing of the building, but there’s so much comedy relief that it’s not the same thing as, say, the huge extended flooding scenes in The Winning of Barbara Worth. Still, you have to be careful to not overplay things or reach a climax too soon. It’s a close balance that’s made easier by Lloyd’s genius.

DH: The late Roger Ebert details this sequence of events: “[Lloyd] ends up scaling the entire building, despite hazards on every floor. A child showers him with peanuts, which attract hungry pigeons. A mouse climbs up his pants leg. A window swings out and almost brushes him to his death. A weathervane changes direction and nearly dooms him. And finally there he is, hanging from the clock. A little later, he does some remarkably casual walking or even dancing on the building’s roof ledge.” What do you do with that crazy material?

CW: Well, you’ll just have to come to see (and hear)! There are plenty of 16th notes and lots of music covered. It IS a riot at mile-a-minute speed. The Lloyd pacing and rhythm is what makes these films a pleasure to work with. He supremely understood timing and the need to match music, and he hands those directly to the accompanist to grab and run with. A Harold film never has any awkward areas or spots where you’re left wondering what to do. Therefore, you’re primed to develop a fast-paced, descriptive, and interactive score. And, of course, the whole idea is to do a dynamic job and yet be subservient to the picture, which is the star of the evening.

Organist Clark Wilson plays a live underscore to the Harold Lloyd silent film Safety Last! on Wednesday, September 6 at 7 pm at Masonic Auditorium as the opening event in the second Cleveland Silent Film Festival & Colloquium. Click here for tickets.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com August 31, 2023

Click here for a printable copy of this article