by Daniel Hathaway

Messiaen occupies a special niche in Paukert’s memory book. The composer and his wife, pianist Yvonne Loriod, visited the Cleveland Museum in 1978 for a series of concerts marking the composer’s 70th birthday. Since that time, Paukert, who also serves as organist and choirmaster of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Cleveland Heights, has played Messiaen’s “nine meditations on the birth of the Saviour” almost annually around Christmastime. His admiration for the work and his command of its colorful music is apparent in his playing.

On Sunday, a large audience turned out to hear Paukert in Gartner Auditorium, the crowd swelled by local organists and members of the congregation at St. Paul’s — along with at least some curious visitors who had probably come to the museum for other reasons. Messiaen’s music isn’t everyone’s tasse de thé, but except for a very few early defectors, listeners paid rapt attention to these hypnotic meditations for the duration of the hour-long performance.

Performing onstage from the auxiliary console of the 1971 Holtkamp organ, Paukert played from a complicated pile of photocopies fanned out across the music rack. Only in the final movement did he share the stage briefly with a pageturner (museum staffer Michael McKay, himself an organist).

Unlike the 1860s French romantic instrument at La Trinité in Paris where Messiaen played for sixty-one years, the McMyler Memorial Organ is an American classical organ with neo-baroque leanings. Nonetheless, Paukert found colorful stop combinations ranging from the piquant to the lush, both for the pictorial scenes (The Virgin and Child; The Shepherds; The Angels; The Magi) and for the more abstract theological meditations on the meaning of the Nativity (Eternal Purposes; The Word; The Children of God; Jesus Accepts Suffering; God Among Us).

In addition to heeding Messiaen’s prime directive, “emotion and sincerity first,” Karel Paukert’s playing was crisp, expressive, and unfailingly accurate. He flew through technically complicated passages with élan and allowed the music to relax completely in moments where Messiaen invites time to stop (like the luxurious melody that unfurls in the second half of Le Verbe). The ninth meditation, Diu parmi nous, is traditionally played to conclude the King’s College Cambridge Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols. Those who have stayed with those annual broadcasts to the end will recognize the piece with which Paukert brought his recital to such a thrilling conclusion on Sunday.

The only elements that went missing on Sunday were the additional sources of sensory stimulation available in a church setting. Gartner simply can’t supply the leftover aromas of incense, the statuary, or the stained glass that create the ambiance of Catholic mysticism the composer had in mind. It might have been fun — though probably impractical — to project some relevant images from the Museum’s collection during the performance. Musicians tend not to need extra-aural stimulation, but other listeners might have found that appealing.

Punch, cupcakes and a tribute from performing arts head Tom Welsh capped off the celebration after the concert. Karel Paukert had to work hard on his birthday, but his admiring fans were very grateful.

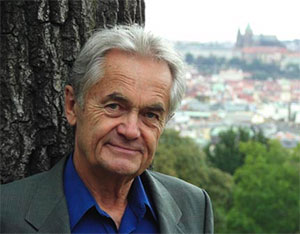

Photos by Lucian Bartosik, courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com January 27, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article