by Mike Telin

On Wednesday, February 25 at 7:30 pm in Cleveland State University’s Drinko Recital Hall and Monday, March 2 at 7:30 in the Studio Theater at Lorain County Community College, pianist/composer Nicholas Underhill will perform two of his own works as well as pieces by Scarlatti, Beethoven, Griffes, Bartók, and Liszt.

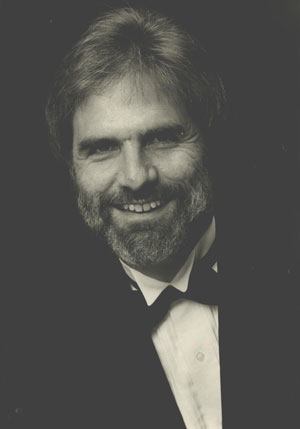

As a pianist, Underhill has performed solo recitals in Carnegie Recital Hall and Merkin Concert Hall and has appeared as concerto soloist with the Cleveland Chamber Symphony, the Ohio Chamber Orchestra, the Lakeside Symphony and the San Jose Symphony Orchestra. He is also pianist for the new music ensemble No Exit.

As a composer, Underhill has been commissioned by The Cleveland Orchestra, the Gramercy Trio, the Ohio Music Teachers Association, The Fortnightly Musical Club, The Cleveland Flute Society, and No Exit ensemble, as well as Cleveland Orchestra players Mary Kay Fink, Takako Masame, Lisa Boyko and Richard King. His first musical score, Remember the Pines, was premiered in the fall of 2014. He currently teaches composition at Cleveland State University.

I asked Underhill to give insights into his program, which will begin with Scarlatti. “Both Scarlattis are early sonatas, the K 14 in G major and K 29 in D major. I was always advised to program Scarlatti sonatas in pairs because they are so short. Interpretively they do present challenges because there are not a lot of musical indications in the urtext editions. For example, tempo indications like presto don’t necessarily mean what they means today, where presto equals 180 on the metronome. So today you hear these pieces played at an alarming speed. I find the D major to be interesting because it has a ‘B’ section which is quieter and more introspective than the more ornate and bubbly first theme. I’m don’t think it requires a tempo change, but certainly a change in character.”

The program continues with the music of Beethoven and Griffes. “I wanted to include Beethoven on this program. The Sonata No. 27 in e minor, Op. 90 is considered by some to be the first of Beethoven’s late sonatas, partly because it is in two movements and the emotion is sort of compressed — there’s no repeat of the exposition. Again, this is an interpretively challenging piece. It’s also a work that for me dates back to my undergraduate repertoire, so perhaps I’m really just trying to make up for the less serene performances that I did when I was 20. I’ll continue with two pieces from Charles Tomlinson Griffes’s Roman Sketches: “Fountain of the Acqua Paola” and “Clouds.” I first learned this set of pieces for a competition, although I have played them quite a bit since then. I think Griffes’s music is so interesting, but today you only hear “White Peacock.” It’s a shame that he died so young.”

The first half concludes with Béla Bartók’s Out of Doors. “This piece takes me back to when I studying with Katja Andy at the New England Conservatory. She was a diminutive woman who stood about four and a half feet tall. One day she saw me in the hallway and said, ‘I have just the piece for your graduate recital,’ and that piece was the Out of Doors. It has a lot of different moods and is kind of like a window into pagan old-world villagers. I remember Katja Andy pointing out that the “Night Music” is very nostalgic, like the cricket sounds in a Hungarian or Romanian forest in the dead of night.”

Underhill will begin the second half with two of his own compositions. “I think I chose Coreopsis (2002) just to show people that I don’t always write interminable fantasy music. I actually wrote Nebulae (2001) by improvising into a midi, which transcribed in a rather haphazard fashion. But I did get some good stuff which I had to edit a lot. It was way too long, but now it’s down to about 14 minutes — a polite length. I’ve always had great success when I’ve played it. I really like the piece, and I wouldn’t like it if I didn’t think it had merit.”

The evenings will conclude with the music of Liszt: Au Lac Du Wallenstadt and the Mephisto Waltz No. 2. “This is familiar music that ends with a bang. But speaking of composer/performers, you do think of Franz Liszt. During his recitals he would play Beethoven, as well as his own music. Then someone in the audience would call out the name of the latest musical, and he’d have to play his variations on that. It’s kind of sad that everyone is such a specialist these days. I really like Liszt, and I think he’s really a futuristic composer in a lot of ways. He took texture beyond what Chopin had done and showed all the different ways that you can play a tune. I wish more composers who write for the piano today would look at the late romantics and learn from what they did with texture and how they used everything the instrument has to offer.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 24, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article