by Mike Telin

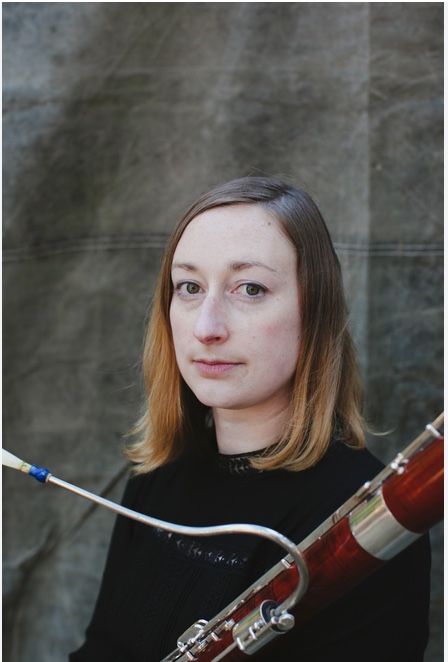

Among the list of distinguished recipients is Dana Jessen, who will receive a mid-career artist prize for music. Jessen is a trailblazer in the world of new and improvised music. Hailed as a “bassoon virtuoso” (Chicago Reader), she is the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship and a Huygens Fellowship. In addition to her active solo career, her resume includes world premiere performances with the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, Alarm Will Sound, Ensemble Dal Niente, Anthony Braxton’s Tri-Centric Orchestra, S.E.M. Ensemble, and the Amsterdam Contemporary Ensemble. As an educator she serves as Associate Professor of Contemporary Music and Improvisation at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music.

I caught up with Dana Jessen by phone and began our conversation by congratulating her.

Dana Jessen: Thank you. I am incredibly honored. I was telling somebody that it felt like the Cleveland Arts Prize was actually looking at all of the things that I do. It’s not just that I’m a bassoonist, but that I also write my own pieces, I play with electronics, and I improvise. I also interpret pieces that I’ve commissioned. And I teach. So it’s very humbling to be seen for the entirety of what I do as opposed to one thing or the other.

MT: How did they notify you that you had won?

DJ: Effie Tsengas, the ED, just gave me a phone call one day — I think it must have been in August. It was actually really funny because I was making reeds so it was a very typical bassoon moment. But I didn’t know who the phone number belonged to, so I just let it go to voicemail. She left a very nice message saying to call her back because she has some good news. And when I called her back, she was very happy to tell me that I was one of the awardees.

MT: Do you think the community has gotten larger since you became involved in it?

DJ: I think we’re at an interesting period in time in which there’s a lot more crossover between contemporary classical music and improvised music. I think that is a new development since I went to the Netherlands back in 2008.

There has always been a little bit of brushing up against each other between contemporary jazz and contemporary classical, and between improvised music in both of those worlds. But I think in the last ten to fifteen years there has been a lot more overlap of those communities where you see contemporary classical people partnering with people who come from a jazz background or from the electronic music world. And you see more ensembles programming Pauline Oliveros and works by George Lewis or members of the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians). And that has not always been the case.

When I started, it sort of felt like I had two lives, the notated life and the non-notated life. And there was a point in which those started to inform one another. For instance, I have this whole thing where I just play the reed alone, and that sound started ending up in compositions. And the lineage of that sound comes from my identity as an improviser. So it’s interesting to see how that started to come together.

MT: How do you teach what you do?

DJ: I teach the Creative Music Lab, which is basically an ensemble. But it’s called that to honor the AACM and their model of blurring these lines of our roles as musicians — they were all writing music, they were all interpreting music, and they were all improvising and doing spoken word and visual art. And that’s kind of what I model the Creative Music Lab around.

In the very first class I teach them Pauline Oliveros’s “Interdependence,” a movement from her Four Meditations for Orchestras. I learned the piece from someone who learned it from her. There is a score, but I only give it to them after we actually do the piece. I like this idea of having an oral tradition around learning. Their instruments are set aside and they make these hocket sounds vocally. Then it turns into hockets with sustained sounds, and then hockets with sustained sounds and some glissando. And that’s the end of the piece. But it allows them to make music as a group, which requires listening, reacting, and making decisions on the spot. But they’re just doing that with their own vocal cords.

In my improv lessons I’ll often play along with the students. I have them write music for their groups that can be a mix of graphic notation with more traditional notation, it all depends on the student. But I do like playing with them — playing with my teacher and improv mentors was important to me when I was learning.

I also teach a free music class. We meet twice a week, and one day is a lecture, discussion, and listening, from a historical perspective that uses the AACM as our starting point. The second day is application, so we play together as an ensemble.

That class was the first curricular offering that I did in this area, and my reasoning was that I often saw schools that had improv ensembles but the students had never heard of George Lewis or the AACM or Pauline Oliverios — all these people I feel are important to know. I want to make it clear to my students that this is not just having the opportunity to play funny sounds together. No, we’re here to make music and art, and there is a history of practice behind it.

MT: Moving to another part of your career, you recently released Set, a recording you made with composer Taylor Brook. In his liner note he says, “Dana, taught me a great deal about bassoon technique during the process.” What did you have to teach him about bassoon techniques?

So, for instance Taylor is really into microtonality and just intonation. And both of those things show up in the piece. Especially in what he calls songs — four distinct notated sections that are set between three improvised sections. Those have suggested ways of improvising while the electronics are reacting to you, and you’re reacting to the electronics. So it’s kind of like a back and forth.

Taylor is interested in microtonality and I’m interested in improvisation, but we were able to find a lot of middle-ground points of connection that we were both super excited about. And I will also give you a fun bit of information, which is that one of the things I shared with Taylor was the Michael Gordon piece Rushes for seven bassoons, and Taylor really liked it. So the last movement of Set is like a microtonal homage to Rushes, which is really cool.

MT: It’s a fascinating album — how long did the project take to complete?

DJ: I think we started sharing things and talking through stuff in 2018. And at the end of 2018, early 2019 we had many conversations and he started to write. We premiered the piece at the end of February 2020, so right before the world shut down.

So we didn’t really think about it for a while. But in 2021 we started communicating again and thought it would be great to record it. And in April of 2022 Taylor came to Oberlin and we recorded it in Clonick Hall.

It took some time to do the release because the label New Focus Recordings had a lot going on, but it was released this past summer and I’m happy with how it turned out. Right now we’re looking for more opportunities to perform it. We want to revive it and get a little more momentum around the piece.

MT: Dana, thank you very much for taking the time to talk. And again, congratulations on the award.

DJ: Thank you. I feel very honored — I’m not someone who gets awards, so I am very honored and incredibly grateful for it. And also, because I really have enjoyed being part of the Cleveland and the Northeast Ohio community — it is a special place. So for me, it’s been very rewarding just to be here, and then to have this honor feels even more special.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 26, 2023.

Click here for a printable copy of this article