by Daniel Hathaway

Two events scheduled for tonight are sold out: The Linking Legacies Project at the Music Settlement and The Cleveland Orchestra with Jukka-Pekka Saraste. That leaves the Baldwin Wallace Symphony Orchestra, which plays at 7 under Doug Droste in Gamble Auditorium, No Exit new music ensemble, who make their debut at the Art Museum at 7:30 with a program of Surrealist films and piano music, Part 1 of Oberlin’s Danenberg Honors Recital at 8 in Warner Concert Hall, and CityMusic Cleveland at 8:30 at Sagrada Familia on Cleveland’s West Side. Visit our Concert Listings for details.

NEWS BRIEFS:

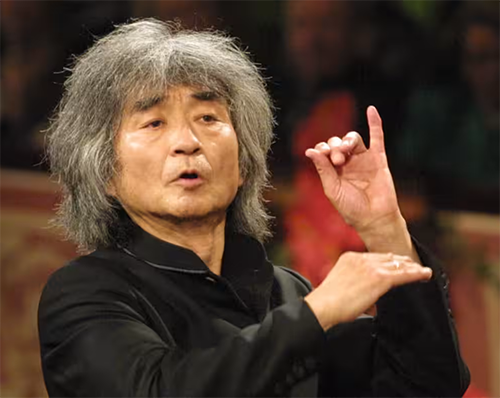

Long-time Boston Symphony music director Seiji Ozawa (pictured above) died at his home in Tokyo on February 6 at the age of 88. In a New York Times obituary, James Oesterreich writes that “Mr. Ozawa was the most prominent harbinger of a movement that has transformed the classical music world over the last half-century: a tremendous influx of East Asian musicians into the West, which has in turn helped spread the gospel of Western classical music to Korea, Japan and China.” Another obituary by Tim Page appears in today’s Washington Post.

INTERESTING READS:

Today’s New York Times carries a review by Oussama Zahr of pianist Vikingur Olafsson’s “spectacular” performance of J.S. Bach’s “Goldberg” Variations on the mainstage of Carnegie Hall. “…intensely emotional and intelligently paced, immaculate in its technique and organic in its phrasing. It was an artistic feat of contradictions that, in the end, felt deeply human.” Read the review here.

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

The Liverpudlians would go on to revolutionize popular music, reinventing themselves more than once without losing their fan base, and venturing beyond the boundaries of pop to harvest inspiration from a variety of sources.

One Beatle, Paul McCartney, dabbled in orchestral music in 1991 when the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Society offered him a commission to mark its 150th anniversary. The result was his Liverpool Oratorio, written in collaboration with Carl Davis, and premiered by the orchestra with singers Kiri Te Kanawa and Willard White, along with the choir of Liverpool Cathedral.

Although the piece was performed globally after its premiere, critical reception tended toward the negative. As Philip Henscher mused in a Guardian article,

One of the reasons such enterprises often fail so dramatically — and it’s very difficult to think of any that have lasted more than a couple of performances — is that their composers rarely have the technical ability to record and convey their intentions with any accuracy.

Many rock musicians can’t read music and have what strikes most classical musicians as rather a loose conception of authorship, relying on amanuenses to transform vague ideas into detailed life. In the world of popular music, such transcribers, arrangers or “producers” have always done a great deal more than the public suspects.

Most of these pseudo-classical works are actually written by teams of professional composers, working on what may be very approximate ideas. … Carl Davis “collaborated” on Paul McCartney’s Liverpool Oratorio — a process eye-openingly described at the time: “Unable to read music, McCartney hums, sings or plays the piano while his collaborator jots down the notes (‘Ah, that’s better – C sharp!’).”

Reviewing the oratorio for the New York Times, Edward Rothstein wrote:

The music’s innocent sincerity makes it difficult to be put off by its ambitions. But the oratorio suggests that the kind of musical and emotional simplicity that make a pop hit can seem barren in the concert hall.

The tale is told of George Gershwin approaching Arnold Schoenberg for composition lessons. “Why do you want to be an Arnold Schoenberg?” the Serialist supposedly responded. “You’re such a good Gershwin already.” As soon as I got home and played Sergeant Pepper in glad relief, I imagined Benjamin Britten saying something similar to the composer of Liverpool Oratorio.