by Stephanie Manning

No concerts to open this week, but the coming days feature offerings from the Cleveland Institute of Music Orchestra, the Chicago early music group Schola Antiqua (pictured), the Resonance Project, and many more.

For more details and see what else is on the calendar, visit our Concert Listings.

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

by Jarrett Hoffman

Anniversaries on this particular date in classical music history go on and on — the birth of Mozart (Salzburg, 1756) and the death of Verdi (age 87 in Milan, 1901) just scratch the surface.

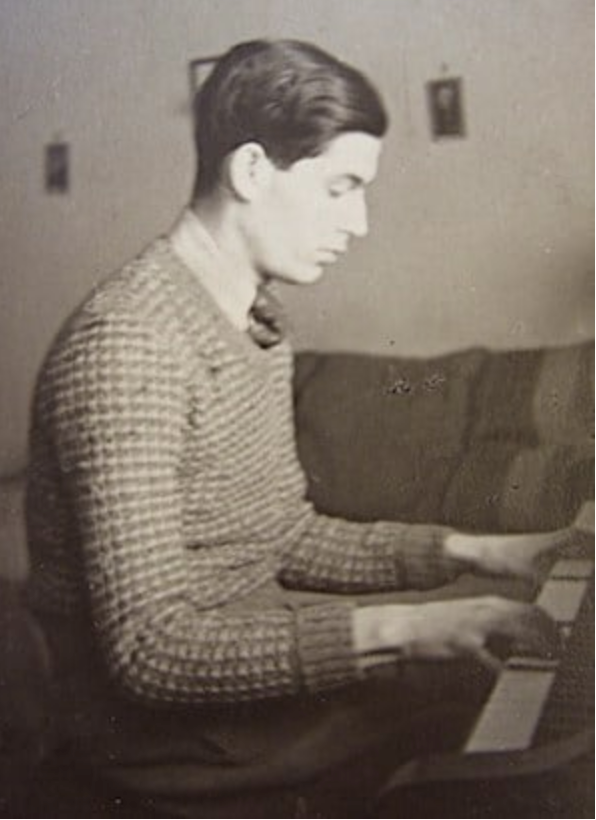

Given that January 27 is International Holocaust Remembrance Day — chosen for the date in 1945 when the Soviet army liberated the Auschwitz and Birkenau concentration camps — we’ll turn our focus to Czech pianist and composer Gideon Klein, who died on that same date in 1945 at age 25.

In 1941 he was deported to Terezín, where he became an important part of the camp’s cultural life — which at first operated in secret, and later under the sanctioning of the Nazis for the purposes of propaganda at this “model ghetto.” As a pianist, he performed works of Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann, Brahms, Suk, Janáček, Schoenberg, Scriabin, and Bach at Terezín, often in programs repeated up to eleven times due to popular demand.

Among several pieces that Klein composed while detained there is the 1944 String Trio. As Lucy Miller Murray writes in Chamber Music: An Intensive Guide for Listeners, you can hear in that work “not only the circumstances under which it was written, but also Klein’s musical gifts that reflected his Czech origins and his admiration of the adventurous Second Viennese School led by Arnold Schoenberg.”

Click here to watch a 2015 performance by students of the Colburn School. The lengthy second-movement Lento, a set of variations on the Moravian folk song The Kneždub Tower, begins at 2:45, and is known to be particularly striking.

In October of 1944, nine days after completing the Trio, Klein was moved to Auschwitz, then to the coal-mining labor camp Fürstengrube, where he died under unclear circumstances. A girlfriend of his at Terezín, Irma Semtzka, had been entrusted with the scores he had written there. After she survived the war, she delivered the manuscripts to the composer’s sister Eliska Kleinova — a survivor of Auschwitz herself — who in 1946 went on to arrange the first complete concert of the music of her brother, Gideon Klein.

You can read more about music under the Nazi regime here from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.