by Jarrett Hoffman

•Oberlin Conservatory students performing on campus and off

•The Eurovision Song Contest, the winning group from Ukraine (pictured), and the flute-like folk instruments heard in their performance

•A woodwind-themed almanac: flutist Marcel Moyse, oboist John de Lancie, and Christopher Rouse’s Clarinet Concerto

HAPPENING TODAY:

Oberlin Conservatory voice and organ majors will stop by the Tuesday Noon series at Church of the Covenant to perform selections from the oratorios of Felix Mendelssohn. Then a 7:30 concert at Warner Concert Hall will showcase the Oberlin Trombone Choir, directed by John Gruber and joined on this occasion by Katherine Jolly as narrator. The program includes music by Paul Dukas, Claude Debussy, Tommy Pederson, Jonathan Bailey Holland, Gustav Holst, Steven Verhelst, George Chave, Giacomo Puccini, and W.C. Handy — details here.

Both events are free, and you can watch them in person or online — click here for the Covenant stream, and here for Warner.

EUROVISION, KALUSH ORCHESTRA, FOLK INSTRUMENTS OF UKRAINE:

On Saturday, twenty-five musical acts took the stage of the PalaOlimpico arena in Turin, Italy for the final round of the 2022 Eurovision Song Contest. After voting was tabulated from professional juries and fans, it was Ukraine that came out on top, represented by the Kalush Orchestra, a band that combines hip-hop with elements of Ukrainian folk music.

On Saturday they performed their song Stefania. Watch here via the Swedish streaming service SVT Play. Written by Kalush Orchestra founder and rapper Oleh Psiuk in homage to his mother, the song has taken on another layer of meaning since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine: an ode to the motherland.

Watching Muzychuk play, you might find yourself wondering if the telenka melody is pre-recorded, since he holds the instrument with one hand at its very tip and doesn’t appear to move any of his fingers.

In fact, the telenka, a type of overtone flute, has zero tone holes. To change pitch, the player varies two things: the strength of their air, and the degree to which they cover the hole at the opposite end of the instrument. (Look closely and you’ll see Muzychuk’s index finger in action.)

YouTube has plenty to offer for anyone interested in hearing more of these instruments. You can hear the telenka demonstrated here, and performed virtuosically here by Myron Blos.

As for the sopilka — traditionally made out of wood, with six to ten tone holes — Maksim Popichuk makes his fingers fly here on that instrument, as well as on the ocarina and the panpipe. And you might find yourself wanting to continue down the YouTube rabbit hole after you hear Popichuk’s clarinetist-colleague pick up the zhaleika later in the video here.

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

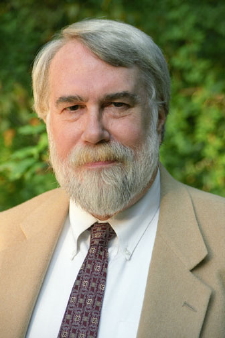

Marcel Moyse is a legendary performer, having played principal flute in several French orchestras, appeared widely as a soloist, and left behind a long list of recordings. His teaching is just as renowned: he was on the faculty of the Paris and Geneva Conservatories, he wrote 37 flute etude books, and gave a famous series of master classes on several continents. He also co-founded the Marlboro School of Music in Vermont, where he moved in 1949.

Pay a visit to the Marcel Moyse Society here, and listen to his short and beautiful recording of Dvořák’s Humoresque as arranged by Kreisler.

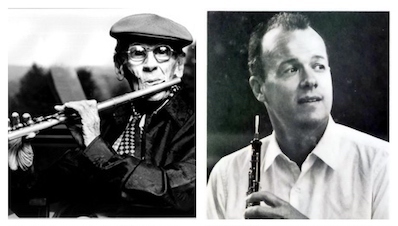

Oboist John de Lancie was born in California, and that’s also where he passed away. But in between, he became most famous for his time in the City of Brotherly Love, holding the principal chair in the Philadelphia Orchestra for over two decades and serving as director of the Curtis Institute of Music for 8 years in addition to teaching at the school.

Although he didn’t commission or premiere it, de Lancie is forever tied to one of the most important works for oboe.

Having served in the U.S. Army in World War II, de Lancie met Richard Strauss in Bavaria following the war, when his unit was securing the area around Garmisch-Partenkirchen, where Strauss was living. He asked the composer if he had thought about writing a concerto for oboe. The answer was no — but in fact, several months later, Strauss was putting the finishing touches on his Oboe Concerto. Listen to de Lancie play it in a recording here.

In the program notes to Christopher Rouse’s Clarinet Concerto, dedicated to Augusta Read Thomas, the composer wrote that it “has taken me longer to compose than has any other score of mine to date.”

The piece that came just beforehand was almost exclusively tonal. “As a result, I felt the need in the Clarinet Concerto to move in a different direction — I have never felt the attraction of repeating myself endlessly and formulaically and like to try to ‘reinvent’ myself from time to time.”

That reinvention took several forms: chromatic and “prickly” language, a one-movement form, and elements of indeterminacy in the composition. “Interjected in my concerto at three points are short three-movement ‘microconcerti,’ their point of interpolation determined by random processes. These microconcerti have a more discernibly ‘classical’ cast to them, and they increasingly have recourse to tonality…”

Those aren’t the only surprises. “Moods change rapidly and usually without preparation,” he wrote. But the greatest difficulty the clarinetist will encounter is undoubtedly in technique. “…the demands placed upon the soloist require almost heroic efforts on his part.”

Click here to listen to a recording by Martin Fröst with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic under the direction of Alan Gilbert.