By Daniel Hathaway

. More music for these Jewish and Christian Holy Days

. Remembering Louis Spohr & Sébastien Érard

MUSIC FOR THESE HOLY DAYS:

With no live performances to note, today, let’s renew the search we began on Monday for interesting recordings of music for Passover and Holy Week.

The central event in Jewish history is Israel’s deliverance from bondage in Egypt, which established the observance of Passover and is celebrated in Psalm 113 (or 114 depending on your numbering system), which has come over into the Christian tradition as well.

Apollo’s Fire presented the debut of Jeannette Sorrell’s edition of Handel’s oratorio, Israel in Egypt last year, which trimmed the piece to a more concise length but preserves the colorful representations of the plagues and the escape through the Red Sea for which the composer is famous. The video is available on Vimeo. Directions here.

There are YouTube videos of performances of Psalm 114 (“In exitu Israel”) by Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville (Les Arts Florissants conducted by William Christie), by Czech composer Jan Dismas Zelenka (Ensemble Inégal & Prague Baroque Soloists under the direction of Adam Viktora), and by English composer Samuel Wesley (double choir motet, Choir of St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, conducted by Barry Rose, from a live BBC broadcast).

As for more Holy Week music, The Guardian must be tapping our phone lines, for that estimable British journal has helpfully put out a special newsletter on the subject.

In ‘Music for Holy Week: a specialist’s guide,’ Edward Breen draws on the vast musical repertoire associated with the week just before Easter, resulting in a fascinating and varied selection encompassing pieces by composers from Thomas Tallis to John Adams. Click here to explore the recommended recordings on the Gramophone website.”

ALMANAC FOR APRIL 5:

by Jarrett Hoffman

German composer Louis Spohr, born on this date in 1784, was a major figure during his lifetime, during which he amassed an oeuvre including eighteen violin concertos, ten symphonies, ten operas, four clarinet concertos, and four oratorios. But his legacy lives on most ubiquitously in two little inventions related to his violin playing and his conducting: the chinrest, and rehearsal letters. He was also an early adopter of the baton.

Despite playing and teaching the violin, and composing so frequently for it, Spohr is best-known today for his clarinet concertos. All four were written for Johann Simon Hermstedt, a court musician and the wind band director under the Duke of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen (to whom Hermstedt also taught the clarinet).

An interesting passage in Spohr’s autobiography shows the composer first praising Hermstedt, then seemingly also taking credit for the success of his friend and colleague. Spohr begins by referencing the Duke’s commissioning of the first concerto (played here by soloist Maria du Toit, the Cape Philharmonic, and conductor Arjan Tien).

To this proposal I gladly assented, as from the immense execution, together with the brilliancy of tone, and purity of intonation possessed by Hermstedt, I felt at full liberty to give the reins to my fancy. After that, with Hermstedt’s assistance I had made myself somewhat acquainted with the technics of the instrument, I went zealously to work, and completed it in a few weeks. Thus originated the Concerto…with which Hermstedt achieved so much success in his artistic tours, that it may be affirmed he is chiefly indebted to that for his fame.

Now hold on just a minute there, Mr. Spohr. As Pamela Weston explains in Clarinet Virtuosi of the Past, the Duke’s appreciation for Hermstedt was such that he might easily have commissioned some other composer — of equal renown — if things didn’t work out with Spohr.

So the moral of the story is: puff yourself up in your autobiography at the risk of getting zinged somewhere down the line.

Louis Spohr’s might be the biggest birthday to celebrate today. But another historical figure — French instrument maker Sébastien Érard, born on this date in 1752 in Strasbourg — offers up the possibility of a tantalizing tangent, and who can say no to that?

First, the background, which is interesting in itself: Érard is famous for making several important innovations for the harp and the piano. Those included a double escapement mechanism allowing for faster repetition of notes on the piano, and a double-action pedal harp which made it easier to change keys. In the first year following that popular advancement — a mechanism still used by modern harp manufacturers — he reportedly made £25,000 (in one conversion, over two million dollars by today’s standards).

A few other interesting tidbits: Érard was the first instrument maker in Paris to fit pedals on the piano, and not just the usual pedals we have today. His instruments (like others in Europe) had several, including a bassoon pedal, which brought leather into contact with the strings to create a buzzing sound. Finally, among the musicians who owned Érard pianos were Beethoven, Chopin, Haydn, Mendelssohn, Wagner, Verdi, Ravel, and Liszt — who was for a time sponsored by Érard.

Now, onto that tasty tangent: the name Érard pops up in a very charming audio play, Elena’s Dream, in which the character of Elena travels back in time, meeting harpsichords — talking harpsichords — from various eras.

In the late 18th century, she encounters the eccentric Thomas Taskin (named after another instrument maker, Pascal Taskin). But moving into the 19th century, she finds that her harpsichord-friend Taskin has been left for dead, tossed into a storage closet at the Paris Conservatory. Harpsichords have been set aside for the new “88-keyed monster” (Thomas Taskin’s words), the piano.

That is, until 1892, when the closet door opens, and Taskin finds himself carried to a stage, cleaned, repaired, and set side by side with a grand piano — Érard. Bickering and name-calling ensue, back and forth between the two proud personalities.

A large audience arrives, and the keyboardist Louis Diémer steps onstage, explaining his “passion for historic instruments” before giving the world premiere of something rare: a “modern” piece for harpsichord, Francis Thomé’s Rigodon (recorded here by Elaine Funaro, like all the harpsichord pieces in the play).

Then Diémer switches over to the piano for Ravel’s Jeux d’eau (recorded by Randall Love). Taskin and Érard earn each other’s admiration and respect — and even get a little flirty in Eric Love’s hilarious writing and voice acting.

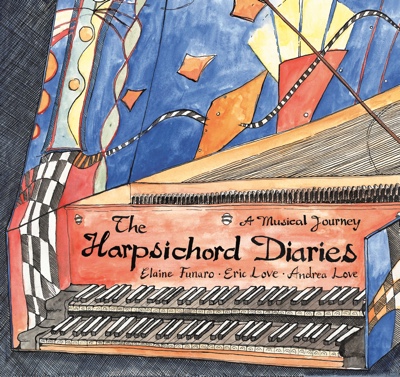

Listen to the whole play here (scroll to the very bottom), or watch a video reading of the children’s book which the play evolved into, The Harpsichord Diaries (pictured above), which adds in beautiful illustrations (Andrea Love) and haiku (Funaro). You can also learn more about both of these projects in a story from Early Music America focusing on the talented family trio of Funaro, Eric, and Andrea.