by Daniel Hathaway

. Trinity Brownbag Concert

. Women’s History Month

. Almanac: Births, deaths, first performances, and a protest in Vienna

HAPPENING TODAY:

Today’s Brownbag Concert at 12 Noon at Trinity Cathedral features the Shaker Heights High School Chamber Orchestra in a preview of their upcoming concert in New York City. See our Concert Listings for details.

ALMANAC FOR MARCH 1:

March is Women’s History Month, which grew out of a national celebration launched in 1981, when Congress passed Pub. L. 97-28 authorizing and requesting the President to proclaim the week beginning March 7, 1982 as “Women’s History Week. Read more here.

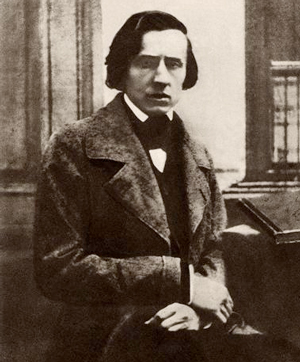

The stork was busy on the first day of March, delivering Frédéric Chopin (pictured above, 1810 in Żelazowa Wola, Poland), Ebenezer Prout (Hackney, London 1835), Leo Brouwer (Havana, 1939), and Thomas Adés (1971, London), while the Fates were snipping the cords of Girolamo Frescobaldi (1643, Rome) and Colombian harpsichordist Rafael Puyana Michelsen (Paris, 2013).

Some famous musical works were birthed (first performed) on March 1: Debussy’s L’Enfant Prodigue (1910, London), Stravinsky’s Petrouchka (1914, Paris), Mahler’s Eighth Symphony (US debut, Philadelphia, 1916), & Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7 “Leningrad” (Kuibishev, 1942).

And on this date in 1919, The Vienna State Opera went on strike to protest the hiring of Richard Strauss, saying he was paid too much and would produce only his own material.

More on Chopin & Adès

by Jarrett Hoffman

It’s interesting to examine the ties between two pianist-composers who share a birthday today: Frédéric Chopin and Thomas Adés.

“He’s the No. 1 piano composer for me,” Adés said of Chopin in an interview for the San Francisco Examiner in 2015. “Listening to his music, the piano is a bottomless pool. His music seems to float freely and rises or falls, seems to have no stability at all…It has this total aquatic fluency.”

Poland’s most famous composer, Chopin was also considered one of the great virtuoso pianists of his time, and that interest certainly played a part in his oeuvre. All of his known compositions include the piano — most of them solo works such as his collections of Études and Preludes, but also two concertos, works of instrumental chamber music, and at least nineteen songs for voice and piano (some have been lost).

And while Adés began his career as a pianist and continues to perform with impressive results (in addition to having made his mark in conducting), he has been clear that he identifies most strongly with pen and ink. “When you come to see me play the piano, you’re seeing a composer who is a pianist,” he has said. The piano has played an important part in his writing, but his most famous works range from opera (The Tempest) to orchestra (Tevot and Asyla, the latter of which made him the youngest winner of the Grawemeyer Award for Composition).

One notable occasion in which Chopin and Adés shared a program was pianist Emanuel Ax’s three-part celebration of Chopin’s (and Schumann’s) 200th birthday at Carnegie Hall in 2010. Partway through the second program, Ax juxtaposed three Chopin mazurkas — a genre the composer made entirely his own, even while using the traditional Polish folk dance as a model — with three Adés mazurkas, Op. 27, that were receiving their premiere.

Critics and musicologists have pointed out similarities between the Adés and Chopin mazurkas, such as the prevalence of three-quarter time, the specification for rubato, and the use of drone — while noting that things are imaginatively a little bit off in the Adés. For Anthony Tommasini of The New York Times, that’s evidenced by spiky harmonies and a fractured sense of rhythm. Paul Griffiths, writing for the Faber publishing company, remarked the “dotted rhythms in triple time and the heave of its shifting accents are now caught from further off, in a stranger world.”

Listen to the Adés Mazurkas here in a live performance by Kirill Gerstein from 2018, and listen to 51 of Chopin Mazurkas here in a playlist of recordings by the great Chopin interpreter Arthur Rubinstein.

As for playing Chopin himself — asked which Chopin Etude he finds most difficult, Adés had a clear choice. “The very first one!” he said in an interview with Elijah Ho. “I tried for weeks and weeks. It should be easy for me because I have extremely large stretch, but that’s obviously one of the things that makes it so difficult — you have to change your hand position…Actually, that was the piece that made me think, I’d better try to be a composer instead!