by Jarrett Hoffman

SAVE THE DATE:

Pianist Evgeny Kissin will visit Cleveland for a solo recital on April 24, 2022 at 7:30 pm at Severance Music Center. The program of music by Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, and Mozart will mark his first performance at Severance since soloing in Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto with The Cleveland Orchestra and conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy in March 1997.

Tickets go on sale October 25, with a limited number of on-stage seats available, and pre-sale for Cleveland Orchestra subscribers and donors is already underway as of yesterday.

INTERESTING READS:

The New York Times shared an important pair of profiles yesterday and today: conductor Eun Sun Kim (music director of San Francisco Opera, and both the first woman and first Asian to hold that post in one of the country’s largest opera companies), and composer Sofia Gubaidulina (before her 90th birthday this Sunday).

And writing for The New Yorker, Paul McCartney himself shares the history of how The Beatles’ Eleanor Rigby came to be — and how the band did as well. “All these small coincidences had to happen to make the Beatles happen, and it does feel like some kind of magic.” Read here.

IN MEMORIAM:

Producer, recording editor, and oboist Thom Moore passed away of cancer on October 16. Moore was a founding member and the president of Five/Four Productions, and was previously the producer and senior recording editor for Telarc International, during which time he won four Grammy Awards.

He studied oboe at the Cleveland Institute of Music, and over the years was principal oboe in such ensembles as Red {an orchestra}, the Cleveland Pops Orchestra, Ohio Chamber Orchestra, Trinity Chamber Orchestra, Cleveland Ballet, Cleveland Opera, and Glimmerglass Opera Orchestra, in addition to performances with The Cleveland Orchestra, Atlanta Symphony, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, and Chautauqua Symphony Orchestra.

Donations in his memory can be made to the Kaboom Collective, aimed at immersing musicians ages 15-25 into many different sides of the arts and entertainment industry.

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

We start with the name of Charles Ives — born on October 20, 1874 in Danbury, Connecticut — but linger there only briefly. (Read our almanac from last year for a deep Ives dive.) Instead we’ll focus on another American composer born on this same date three years later in Louisville, Kentucky who was also an authority on folk music, in her case of the Southern Appalachians.

That would be Josephine McGill, whose book Folk-Songs of the Kentucky Mountains, originally published in 1917, contains ballads and other English folk songs “notated from the singing of the Kentucky Mountain People” after her visits to Knott and Letcher Counties, and arranged with piano accompaniment by McGill herself.

Thanks to the digital offerings of the library of the University of Kentucky, the entire book is accessible for free. Warm up your vocal cords and dig in for some sight-singing — but please, first lock yourself in a sound-proof room. (And that’s not a commentary about the quality of the music.)

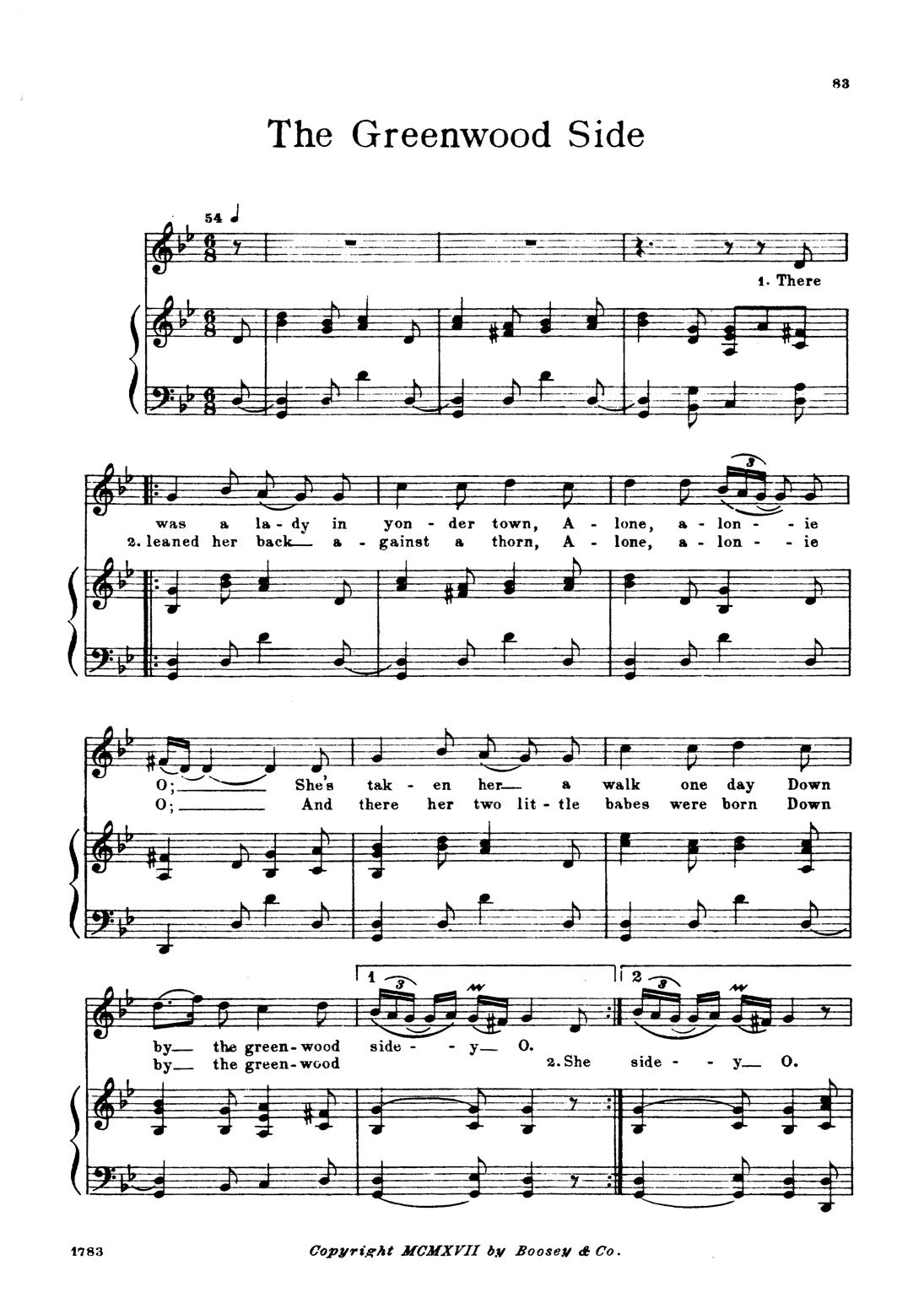

After thumbing through the book, focusing in particular on the ballads, which McGill notes are particularly valuable from a literary perspective, I discovered at least one gem: The Greenwood Side, also known as The Cruel Mother, on page 83. It jumped off the page with its dark lyrics (a mother kills her illegitimate children before meeting their ghosts) and its tune, both mournful and slightly bouncy in 6/8 time.

Then, turning to YouTube, I discovered — patting myself on the back for my good taste — that The Greenwood Side is already quite well-known, famously recorded by such figures as Joan Baez, Peggy Seeger, Ian & Sylvia, and Judy Collins.

Outside of the folk tradition, the song has also made its way into the realms of jazz — via the Paul Winter Sextet’s album Jazz Meets the Folk Song — and classical. Harrison Birtwistle’s 1969 opera Down by the Greenwood Side was inspired by both that ballad and English folk plays (but the only audio I can find is of brief rehearsal footage).

To me, the Seeger rendition stands out for its simplicity — just a lone voice — as well as its modal melody, upbeat tempo, and understated approach to emotion. Ian & Sylvia’s take is similar, but harmonized and slower. The Baez and Collins versions, meanwhile, add important context in the opening lyrics with the mention of the woman’s betrayal at the hands of an older man.

Sadly, none of the recordings I’ve found follow the music as written in McGill’s collection. They aren’t even particularly similar. “It has been said that a good melody is not for an age — but for all time,” McGill writes, and I think that’s true of this version.

I told you before to warm up your vocal cords. Now get recording.