by Daniel Hathaway

Bruce’s Lick Quartet, a commission for the Dover by the Dallas Chamber Music Society and the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, confidently walks the borderline between classical and jazz idioms. It takes its title from “a melodic fragment that has been used by countless jazz musicians over the years, and more recently has become something of a joke, an internet ‘meme,’” as the composer wrote in his notes.

Bruce went on to say that because early sketches for the quartet began to resemble “the lick,” he decided to challenge himself to use that gesture unironically and in something of the same subliminal way that Shostakovich embedded his initials in the Eighth Quartet.

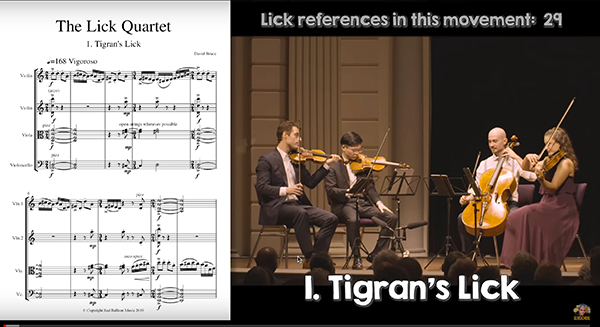

The resulting piece pays homage in its four movements to the rhythms of Tigran Hamasyan (“Tigran’s Lick”), the “sunny simplicity” of Dvořák (“Antonín’s Lick”), the complex jazz meters of Jacob Collier (“Jacob’s Lick”), and the general quirkiness of Janáček (“Leoš’s Lick”).

The piece sounds much more straightforward than its notation implies, and the Dover must have slaved over it for hours to make it flow. A YouTube video of the Quartet at the Concertgebouw shows score and performance side by side.

By December 3 in Cleveland, the Dover had relaxed into their formidable task, giving an exuberant reading of The Lick Quartet that was fun to listen to. Tigran’s movement was like a string quartet hoedown with an abundance of offbeat strokes. Antonín’s was peppy and modal-sounding. Jacob’s was busy and restless. Leoš’s was energetic and repetitive, prophesying a vision of Czech minimalism.

Benjamin Britten’s Quartet No. 1 in D came together in a California cabin in 1941, and reflects the anxiety the pacifist composer suffered about the Second World War. Its shimmering gestures, diaphanous textures, angular themes, and tangled motives must have sounded disquieting to mid-century ears. The third movement, Andante calmo, offers some respite, despite some Purcellian cross-relations and its exploration of both high and low registers, soon countered by spinning fragments and big unisons over nervous cello figures in the finale. The Dover gave the Britten a clean, sensitive reading.

The ensemble sent the audience off into a chilly night with a warm, responsive reading of Brahms’ Quartet No. 3 in B-flat, which toes the line between convention and innovation as effectively as the Bruce quartet did between genres. Violist Milena Pajaro-van de Stadt shone in her third-movement solos.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com December 17, 2019.

Click here for a printable copy of this article