by Max Newman

That’s how Korean flutist Jasmine Choi described George Crumb’s avant-garde 1971 composition Vox Balaenae, or Voice of the Whale, during a recent conversation. That work for electric flute and cello and amplified piano will be performed on Saturday, June 15 at 7:30 pm at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History as part of ENCORE Chamber Music. This year the festival is themed around “Planet Earth” with the aim to “highlight the universal connection that we humans have with nature,” according to founder and artistic director Jinjoo Cho. Tickets are available online.

Jinjoo Cho and Jasmine Choi’s connection is a long-standing one, the two having known each other since attending the same middle school in Seoul. It is in part this relationship that is bringing Choi to Cleveland for this performance. “She reached out to me last year to ask me about this project, and I’ll always say yes to Jinjoo. I’ve always wanted to perform with her.”

There were also musical reasons for Choi’s eagerness to perform Voice of the Whale. “I was always looking for the right opportunity to learn it. This is one of those pieces that you don’t just learn for no reason — I needed to have a concert in order to fully delve into it. I think it is a perfect fit for the occasion, as well.”

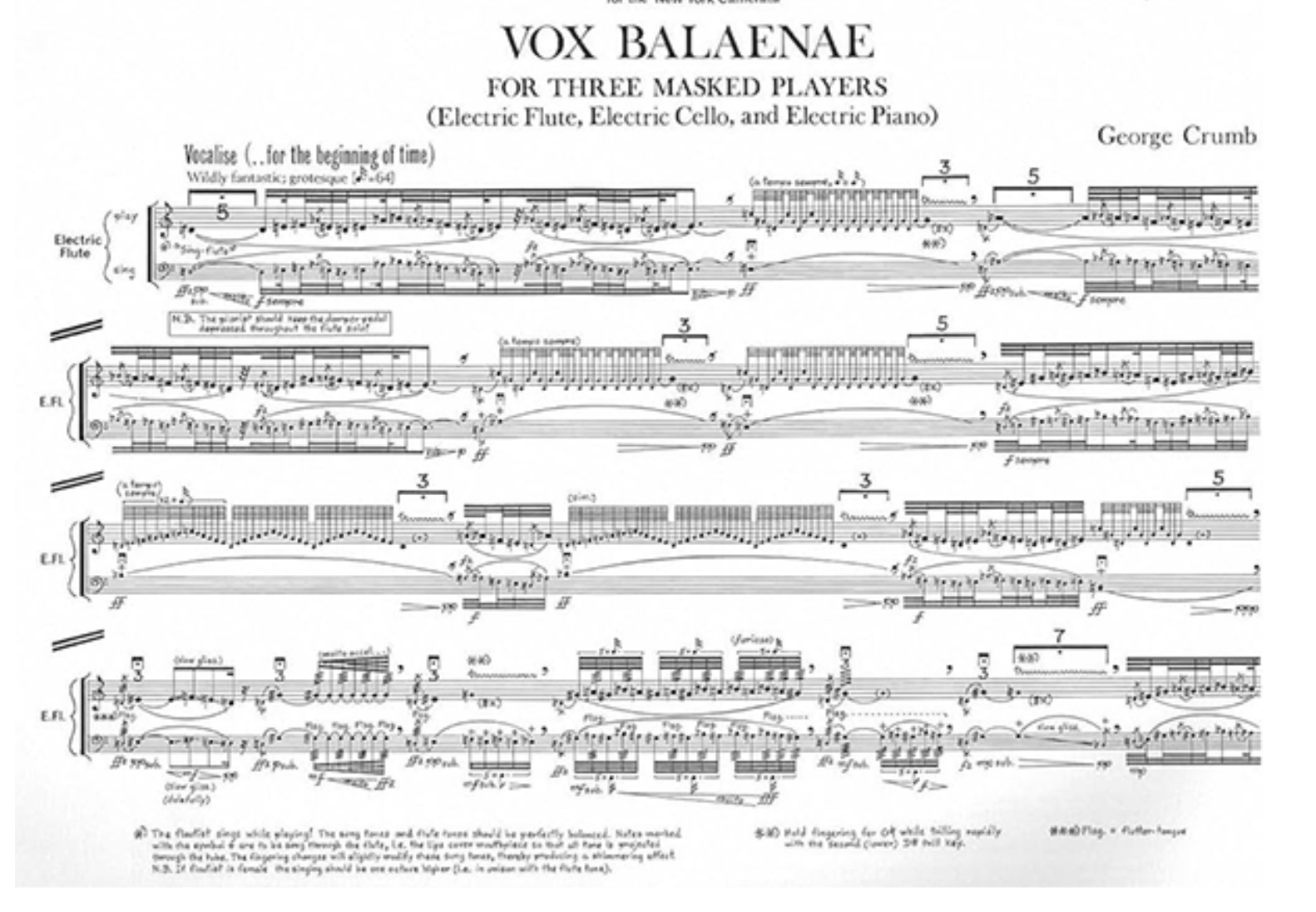

Originally inspired by an audio recording containing the songs of whales as they traversed the seas, Vox Balaenae is around twenty minutes long, grouped into eight movements, and is wonderfully experimental from start to finish. Crumb emulates whale noises with a variety of unique instructions for the musicians: the cello part utilizes unconventional tuning and eerie harmonics, and the piano part involves strummed strings. For a piece that premiered in 1971, this was certainly groundbreaking material. “It must have been a real shock for both the performers and the audience,” said Choi.

For the flute part, the performer must perfect the difficult skills of singing into the instrument while playing, flutter-tonguing, and executing complicated trills. For Choi, these instructions were rather daunting upon first glance. “When you look at the piece, it’s really complicated, almost intimidating. I didn’t know where to begin — the trilling in particular is very complex. But once I got into it, it wasn’t that scary — I basically took it one very small part at a time. Many of the extended techniques are actually pretty standardized these days.”

Another part of the score that was initially surprising to Choi was the instruction for the piece to be performed on electric flute. “I was thinking, ‘I cannot play the electric flute, whatever that is.’ Because when you think about an electric guitar, you have it plugged in with an amplifier. So I thought, do I need a different type of flute? But actually, it just means that we are all mic’d up. We’re all being amplified, and he just notated it.”

Crumb also includes a plethora of staging instructions, advising the performers to wear black half-masks, and for the stage to be illuminated in blue light. According to Choi, these are vital components of the performance, especially in terms of the thematic message that they send. “When these whale noises are put to music with the masks and the blue light, it gives the audience so much inspiration. It evokes some deep feeling inside that we are actually just parts of the universe, that the whole world is much bigger than us. This piece, it really creates this energy that makes you feel that we are connected to mother nature.”

It is important, Choi says, for the musicians to try to maintain the natural feeling of the piece. “As performers, when we look at the piece, we often get into the score a little too deeply, too literally. For me, playing everything to the letter, and at the same time sounding as natural as possible, has been challenging.”

Choi also discussed her preparations thus far and how they will evolve when she meets her fellow performers, cellist Max Geissler and pianist Shuai Wang, and gets to the venue. “When I practice at home, it’s only me in my room. But whenever I go to the venue, I see my sound as extended through the concert hall itself. So I have to use the space I’m in to create a certain sound.”

In addition to Voice of the Whale, Choi will also be performing Johannes Donjon’s Rossignolet – The Nightingale for piano and flute, a Romantic piece representing the song of a bird. “These two pieces are completely contrasting,” said Choi, “but I think it will work very well in the context of the program.”

Aside from her visit to Cleveland, Choi and I also discussed her storied musical journey that began in early childhood. Born into a musical family, Choi grew up going to her relatives’ recitals and listening to classical music. The flute therefore came to her very naturally. At the age of 16, she was accepted into the Curtis Institute of Music, where she studied with a variety of virtuosos that were “huge influences.” After college, Choi spent six years in Ohio as associate principal flute of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra.

At this point, Choi successfully auditioned for the Vienna Symphony in Austria, a nation where she still resides today. “It was really life-changing for me to live in another culture with a different language. I felt like I was really swimming in a big ocean of music.”

Currently, Choi is working very successfully as a solo artist. “At one point, I was doing more than 90 concerts per year. It’s been a great privilege for me to be able to travel the world and perform. Still, there are many places I haven’t been, which is an exciting part of going somewhere like Cleveland next week.”

For Choi, her work goes beyond music. There was a certain point in her life when her career path began to trouble her. “When I was in my twenties I had this realization where I felt like I couldn’t help the world with music. What I was doing felt really selfish to me. I felt like, if I didn’t play the flute, there would be other flutists who could replace me. I felt like I couldn’t make an impact on so many bigger issues.”

But it was at this point in her life that Choi had another realization. “I found myself gaining so much comfort from listening to music. I was feeling like, ‘I’m so glad Mahler wrote his Ninth Symphony. I’m so glad Schumann wrote Kreisleriana. It’s really healing to my soul.’ And I began to think that maybe somewhere there’s someone who’s thinking, I hope Jasmine Choi keeps playing. I hope she never quits. I’m waiting for her next album. And that thought really brought me back on track. Maybe, in my own way, I am helping the world. As musicians, we cannot stop war, but we can still connect the world in a better way. We are speaking the universal language.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com June 11, 2024.

Click here for a printable copy of this article