by Daniel Hathaway

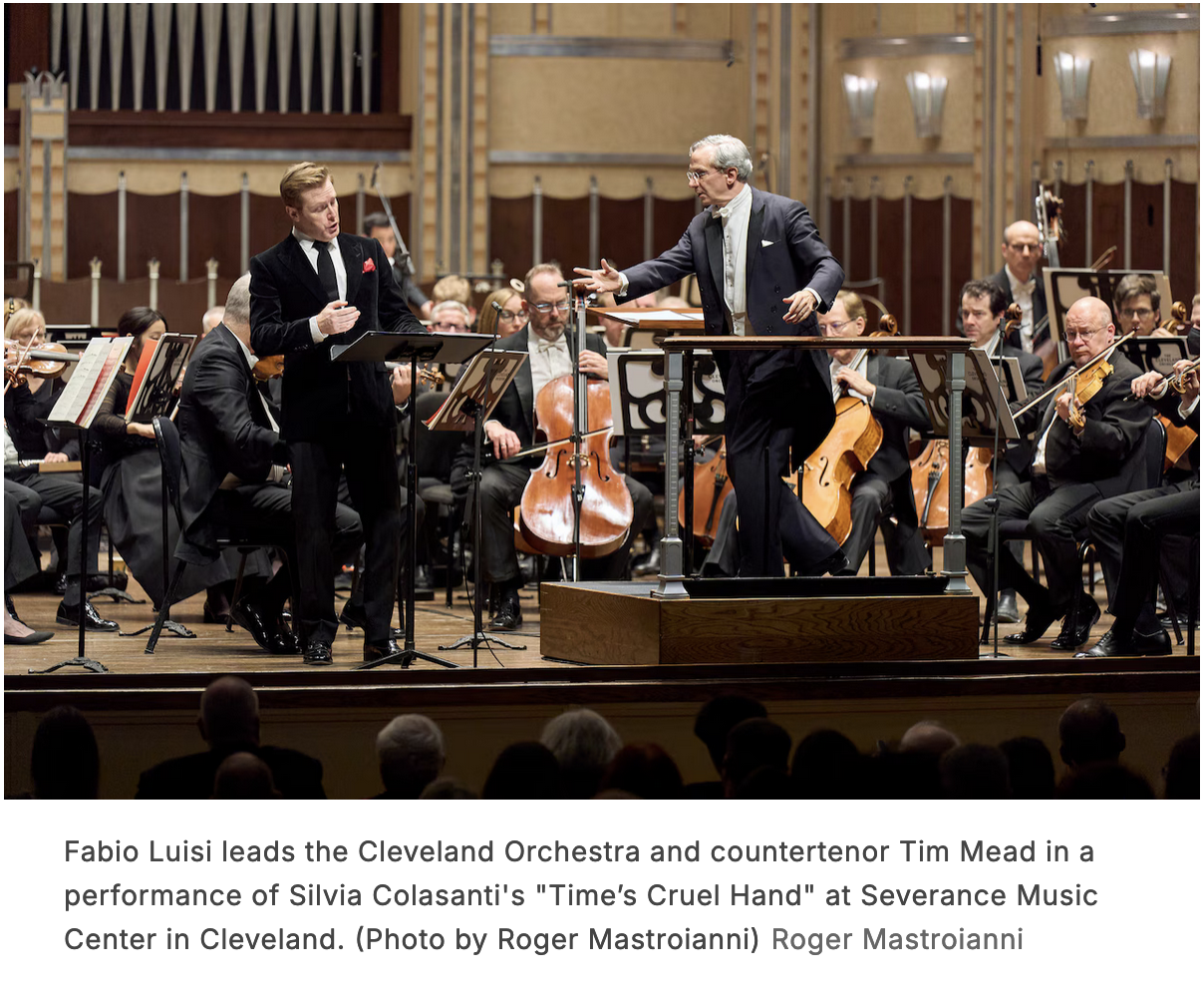

CLEVELAND, Ohio — An odd but fascinating pairing brought the U.S. premiere of Italian composer Silvia Colasanti’s Time’s Cruel Hand and the 1888 version of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7 together on the same program in Mandel Concert Hall at Severance Music Center on Thursday, February 13. Fabio Luisi, music director of the Dallas Symphony, led resplendent performances of both works.

In addition to the striking contrast between their musical styles, the two pieces clock in at 20 and 65 minutes respectively — a conundrum for program planners, whose tasks would be much easier if composers would just format their orchestral works in neat, 30-minute packages.

Colasanti’s piece deals with one of the English Elizabethan period’s pervasive literary themes: Mutability, or the tendency of things to change — and decay — over time. Three sonnets on that subject by William Shakespeare are sung by a countertenor, who brings an otherworldly quality to the subject and in the end asserts that the ravages of time and memory are counteracted by the healing power of music.

Tim Mead was the expressive soloist, whose rich, clear voice easily rose above string tremolos, bass drum, and tam-tam in “Time Will Come.” His lovely, lyrical lines emerged out of clouds of orchestral color, and his impressive vocal technique served him well where Colasanti wrote long high notes with decrescendos.

At one point in “Devouring Time,” Mead unmasked his natural voice, effortlessly descending into his baritone range and back again. And in “Time’s Cruel Hand,” where winds and muted trumpets produced an array of colors and concertmaster Lyiuan Xie contributed a lovely solo, Mead held a long, final high note until a pizzicato brought this mesmerizing piece to a conclusion.

After intermission, the stage was reset for a large orchestra, including four Wagner tubas that enriched both the sound and visual appeal of the gleaming brass section in Anton Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony.

Conducting bare-handed, Luisi drew a rich, well-blended sound from the ensemble. The brass was especially powerful without ever becoming overbearing. Subtle tempo and mood shifts along with sudden changes of themes were full of color and played with rhythmic precision. It’s worth remembering that Bruckner was an accomplished organist whose orchestral works are reminiscent of free improvisations.

The opening cello line with horn was beautiful, and the march motifs stirring. At the end of the first movement, the dynamics and tension grew dramatically and the final release was captivating.

In the second movement Adagio, marked Very solemn and very slow, Luisi paid close attention to Bruckner’s tempo markings, and created a stupendous arch. Here the glorious sound of the Wagner tubas, tuba, and horns rang in the hall.

After the emotional weight of the Adagio, the playful Scherzo provided necessary relief. The recurring trumpet calls were brilliantly played by Michael Sachs. Everything kept growing exponentially until its sudden ending.

Marked Animated, but not fast, the last movement begins with a jaunty mountain tune before the mood shifts into a solemn, sonorous brass chorale.

Throughout this performance it was clear that The Cleveland Orchestra has Bruckner firmly implanted in its soul, something that was gratefully recognized by the audience immediately after the final chord had faded.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 19, 2025.

Click here for a printable copy of this article