by Jarrett Hoffman

Taking the composer’s suggestion, ChamberFest Cleveland will cast a deep blue light over the stage of Mixon Hall at the Cleveland Institute of Music on Thursday evening, June 21, when they present Crumb’s underwater epic as part of a 7:30 pm concert titled “A Turn in the Road.” The program will also include Dvořák’s Piano Trio No. 3 in f and the “Adagio” from Berg’s Chamber Concerto.

I recently spoke with Scottish-born Lorna McGhee, principal flute of the Pittsburgh Symphony and professor at Carnegie Mellon University. She’ll make her ChamberFest debut on Tuesday, June 19 at 7:30 pm at the Crawford Rotunda at The Cleveland History Museum, where she’ll perform Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s 12 Miniatures for Flute and Piano. Then on Thursday, she’ll play Vox Balaenae.

The first item on our conversational agenda? Whales.

Lorna McGhee: If you’ve listened to the sound of humpback whales singing to each other, you know it’s amazing what George Crumb has done to evoke that. The whales can hear each other through vast distances in the ocean — and maybe we don’t know exactly what it means, but we know that they’re communicating with each other in their own way. It’s almost like the piece represents an awareness of all these other lives going on in parallel to our own existence.

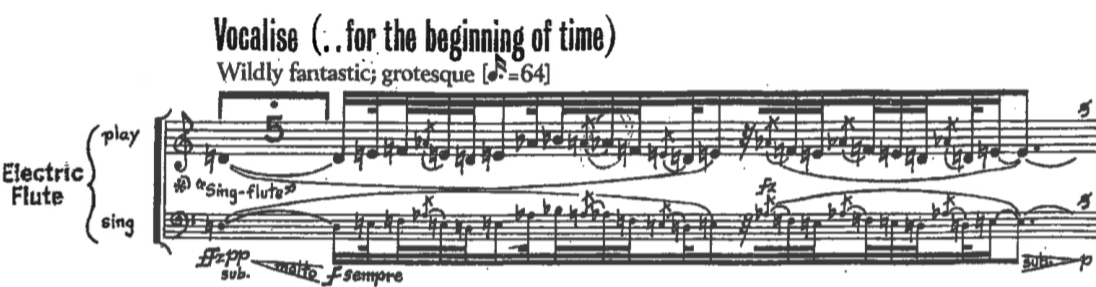

Jarrett Hoffman: You get to open the piece with that sound that flutists can make so well: singing and playing simultaneously. What does that feel like, and why does Crumb put a spotlight on it?

LMcG: Actually, it’s great. In my warm-up, I sing and play a lot because it encourages this very free and natural way of blowing out through the instrument, and sort of wakes up all the resonators in the body, like in the head and chest. It’s a wonderful tool to help open up your sound.

But the effect in the piece is quite shocking — it makes me think of the Inuit culture and their transformation animals that are half-human, half-animal. In a way it’s this threshold between our normal world and this incredible world in the deep oceans that we hardly know anything about. And there’s a terrible melancholy in the lines that Crumb writes.

In some places you have to entirely cover the embouchure hole and just literally sing through the flute while you change fingerings, which creates this rippling effect over the voice. That is more otherworldly — less human, even.

JH: After singing and playing for quite a while to begin the piece, you’re then asked to simply play — which then sounds somehow surprising.

LMcG: That’s right, it suddenly sounds very bright and quite piercing. It’s almost like the music is saying, “Pay attention.” Then there’s the parody of Also sprach Zarathustra in the piano, pointing out the absurdity of man’s dominance.

There are also incredibly peaceful moments in this piece that make you think of the serenity of the ocean. When the cello comes in with these very high harmonics, it’s like the whale songs across vast distances. And there’s the incredible effect in the piano, where the pitches are bent with a chisel on the strings, or played with a paperclip to create this buzzing noise. The sections of the piece represent different phases in the evolutionary process, so you can imagine these sounds symbolizing the life forms coming into being.

JH: At one point Crumb asks for “speak-flute.” What is that?

LMcG: It says to whisper in the part, but you have to actually speak in quite a breathy way over the embouchure hole, so you get a tiny bit — maybe 5% — of pitch. The flute acts a little bit like an amplifier, giving it another color.

JH: Tell me about the last movement, the “Sea Nocturne,” which asks the flutist and cellist to also play crotales.

LMcG: That’s quite nerve-wracking. But the ending is so moving, with the beautiful repetition of the piano part, the very high harmonics, and the fragments of the melody from the flute and voice at the beginning — it’s like these remnants of the whale song are just gradually fading out, with the gentle, magical shimmer in the piano.

It’s this gesture of something fading into the distance, whether that’s the whales going to another part of the ocean or dying out. There are so many ways you can relate to it, but something beautiful is passing out of sight. The simplicity of it and the innocent sound of the antique cymbals make it really powerful at the end. And the piano keeps going — just fading out, fading out, fading out.

This piece always gets me. I think it’s one of those works of contemporary music that hits on some kind of truth that you can’t necessarily put into words, but it resonates. It’s also the kind of piece that opens up your ears to hear the instruments in a way you’ve never heard them before. I just think it’s magical, really one of the great pieces of contemporary music, and not to be missed.

JH: Will the three of you be wearing the black half-masks that Crumb asks for?

LMcG: We haven’t decided. Some of the players wear glasses, so there’s a practical consideration. I’ll tell you my personal take on it: I’ve played it in masks before, and sometimes I think the masks actually draw attention to us. The original intention was to negate the performers in a way, to put the focus not on us but on the message. It’s like the parody on Also sprach Zarathustra — it’s a gesture against the dominance of mankind over the planet.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com June 19, 2018.

Click here for a printable copy of this article