by Daniel Hathaway

Violinists Carrie Krause, Johanna Novom, Adriane Post, and Karina Schmitz will take turns playing nine of the fifteen virtuosic pieces that make up Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber’s “Rosary” Sonatas — musical meditations on the five Joyful Mysteries, the five Sorrowful Mysteries, and the five Glorious Mysteries of the life of Christ. Probably written in the 1670s, but unknown to modern ears until first published in 1905, the devotional work is preserved in a beautiful manuscript held in the Bavarian State Library.

The sonatas are pictorial and expressive, but a special feature of the collection is Biber’s requirement that the violin strings be re-tuned for most of the pieces after the first sonata. This practice is called scordatura. “What I love about it is that it changes the resonance of the instrument so much,” Karina Schmitz said in a telephone conversation. “Keys were so important back in the Baroque. D-minor was such a noble, solemn, reflective key, and to have an instrument that resonates so gloriously in that tonality really opens up possibilities. You get these enormous four-note chords that are easy to play and make the instrument explode with sound. Then there’s a sonata where the tuning is super tight and compact, and creates a very intimate feeling.”

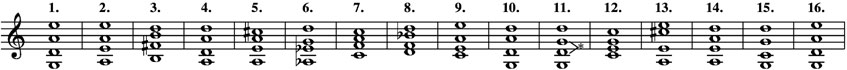

Johanna Novom said, “The Agony in the Garden uses the most human tuning and the most tragic one. It’s very dark, with the strings tuned to A-flat, E-flat, G, and B. In contrast, The Resurrection [score pictured below] has the brightest and most open tuning — two pairs of octaves G-G and D-D — which makes it sound otherworldly. It creates a bell-like quality that’s quite transcendent.”

Carrie Krause agrees that it can be disconcerting to hear yourself playing notes different from the ones you see in the score. “It does freak you out. You have to rely on your muscle memory and make sure you have your fingerings clearly marked — because you’re not going to be making those up in the moment.” Krause chose the Jesus at the Pillar and Ascension sonatas, “ones that really grabbed me. For The Ascension, the violin is tuned in C, a very resonant key that gives the effect of drums and trumpets.”

I asked all four violinists in separate telephone conversations how they decided to take up period violin playing. For three of them, violin professor Marilyn McDonald and the Oberlin Conservatory played a central role.

Novom also plays in the Diderot Quartet, which is in residence at Washington Cathedral. She agreed with Post. “It was just a natural progression. I didn’t think I’d end up spending 90% of my professional life playing period violin, but the more I did it, the more I wanted to play even later music on gut strings.”

Schmitz started out playing modern violin, but one day she suddenly found herself with a different instrument in her hands. “I was thrown right into playing viola for a Hindemith quartet. Someone taught me how to read alto clef and there I was fifteen minutes later sitting in that quartet.” She took up period violin at Oberlin. And dealing with different clefs between violin and viola helped prepare her for the Biber scordatura disconnect. “I treated the score like tabulature — I figured out where a certain note was on the staff and that became what finger I had to put down. Now if I look away from the music long enough and start playing it by ear, the fingers go down in the wrong place. It’s a total mind-twister.”

Krause, the only non-Obie of the four, started out as a modern violinist at Carnegie-Mellon in Pittsburgh. “One day my teacher said, ‘Why don’t you learn the Devil’s Trill sonata while I’m on tour?’ I played it for him when he got back and he said, ‘This really isn’t working. Why don’t you learn this piece in the Baroque style?’ I went to hear Julie Andrijeski, listened to every recording I could get my hands on, and just fell in love with the instrument.”

Krause moved on to graduate school at CIM and played in the Case/CIM Baroque Orchestra, where she got to work with Apollo’s Fire and visiting players coming through town. “Julie was still in Pittsburgh, and I drove back to take lessons from her. She wouldn’t let me pay her. She said, ‘Open a bank account and put all the money you’d pay me in there and work toward getting an instrument.’ It was really amazing.”

These days, all four violinists are members of a widely-dispersed period instrument community that comes together for projects in various places. I could have sat down with three of them in Boston last week — all were playing in the same Handel and Haydn Society performance. Meanwhile, Krause was on the opposite coast, deplaning for a gig in Seattle. The Fairbanks, Alaska native makes her home in Bozeman, Montana.

“It’s kind of the final frontier, so there’s a lot of opportunity to create things,” she said. “I have a non-profit concert series there with really enthusiastic audiences. I started a group called the I-90 Collective ten years ago with Seattle colleagues, and Adriane is also involved. We primarily do house concerts around the state, sometimes in rural areas where people have never heard period instruments before. We also hold a workshop in Bozeman for about fifty students who are interested in learning Baroque style. We have a house in the mountains where we can host everybody, talk about Biber over breakfast, and do some hiking after rehearsing.”

All four soloists are stoked about this weekend’s Biber performances. “We’ll give the audience a nice taste of the pieces without being completely exhaustive — and exhausting,” Novom said. “There will be a few lute and keyboard interludes, and at the end a beautiful motet by Forester we’ll all play together with two violins taking the place of two sopranos — singing through our violins.”

Krause agreed. “The way it’s being presented with a variety of musicians is going to be fascinating to hear. The pieces each have such a unique sound because of the tunings of the instrument. They’re also just such dramatic pieces that tell a story in quite a descriptive way. There’s a lot to hang onto. It would be amazing to hear the entire collection, but this is a very palatable program.”

Performances take place on Thursday, January 31 at 7:30 pm at First United Methodist Church in Akron, on Friday and Saturday, February 1-2 at 8:00 pm at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Cleveland Heights, and on Sunday, February 3 at 4:00 pm at Rocky River Presbyterian Church. Tickets are available online.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com January 29, 2019.

Click here for a printable copy of this article