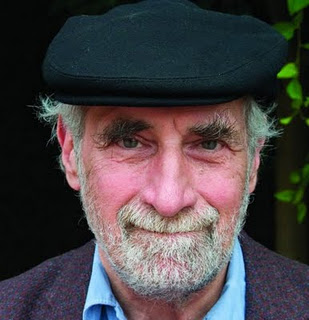

by Daniel Hathaway

Daniel Hathaway: You studied at Harvard with Walter Piston and Randall Thompson? Was there a certain moment when you made a switch in your musical style?

Frederic Rzewski: I hope at least one moment, probably many.

DH: But it’s a long way from Walter Piston and Randall Thompson to what you’re doing now.

FR: Well, I never wrote music like Randall Thompson or Walter Piston. But especially Randall Thompson was important to me. He was my teacher of counterpoint — modal counterpoint. And I think a very good teacher, also. He certainly understood and loved it, which seemed to me the most important thing about teaching counter-point: you actually have to love it. It can be very boring. But one thing I remember about that class is that he made us sing our exercises. It wasn’t enough to write them — we had to sing them. He always insisted on that.

DH: That might have been painful for some people to do.

FR: No, I don’t think so. But for him it was important. Of course, he wrote all this choral music, so he understood it from the inside — it wasn’t just a dry academic exercise.

DH: What first began to steer you in the direction of new music and improvisation in particular?

FR: Good heavens. I don’t know. It depends on what you mean by new music. I started the piano when I was four years old, and not long after that I started writing things. When I started bringing my teacher strange sounding chords and so forth, he didn’t really approve of that. But he said, “if you have to do this kind of thing, you should listen to the people who do it best. First of all, you should listen to Shostakovich. You should also listen to Schoenberg.” I must have been about ten years old at that time. I lived in Westfield, Massachusetts, and my teacher lived in Springfield, about ten miles away.

I used to take the bus from Westfield to Springfield and then change to the bus to go to my music lesson. And at that place there was a record store. This was 1948 and the LP’s had just started coming out. So you could take out a record and go into a little booth and listen to it — that’s how I heard a lot of things. So I went in there after that particular lesson and I said “do you have anything by Schoenberg?” and he said, “yes, this just came in,” and he handed me Schoenberg’s Survivor from Warsaw. So I took that into the booth, and that was the first time I encountered anything like that. You can’t do that in Springfield, Massachusetts anymore. Just to point out how times have changed.

DH: That made an impression, I’m sure.

FR: Very much. But no, I can’t pinpoint a single, particular moment when I made up my mind to do one thing and not another. (Laughing) I still can’t make up my mind. I went through several phases, When I was at Harvard, it seemed that everyone there was writing neo- classic, post-Stravinskian music. I got interested in the other side, Schoenberg and Webern and soon after that, things like John Cage and Stockhausen. Then I became Stockhausen’s pianist for a while when I went to Europe in the sixties.

DH: What was Stockhausen like to work with?

FR: Very stimulating. Not an easy person to get along with, but certainly full of ideas. Yes, I think I got a lot from working with him — a certain attitude, perhaps. One interesting thing about that composer was that he had no doubts at all in himself, which is an unusual trait. Most artists are not very secure people, I think. Just to take a few examples: Shakespeare and Michelangelo, both of whom seem to have gone through periods of depression and self-doubt, and this a very common trait. It was one that was totally absent in Stockhausen’s case (laughter). That’s one of the things that fascinated people, I think.

DH: When did improvisation become an important issue in your music?

FR: I always improvised at the piano when I was a child, but I didn’t get seriously involved in it until the sixties when I was living in Rome. This was the time, of course, when free jazz was exploding. There were many artists of all kinds in Rome at that point — it was a very exciting place to be. I got together with a bunch of people who were all interested in live electronics. Of course, live electronics was a field in which improvisation is just a natural thing. We really didn’t know what we were doing, and probably came close to electrocuting ourselves on a number of occasions (laughter). Luckily, we avoided catastrophes, but probably just barely.

DH: Are you doing any teaching these days, or mainly writing and performing?

FR: I’m not really doing any teaching, except when I come to American universities where I do short stints. No, I’m mostly playing and working on my own.

DH: You have a fascinating program planned at the Art Museum. Tell me how Mendelssohn and The People United fit together.

FR: That’s actually rather interesting. I didn’t really notice the parallels until some years ago. Of course I knew the Mendelssohn since a long time ago, but I never paid too much attention to it until maybe ten or fifteen years ago. I forget exactly when I happened to stumble across an old copy of the score and started looking through it. I realized that the work has a structure which is not unlike The People United. There are eight books of Songs Without Words. Each book contains six songs. This is already a striking technical feature of this work. It’s not usually regarded as a unity, it’s usually taken as a sort of collection of small pieces which are usually performed individually, separately from each other. But as I started to look carefully at this music, I realized that this is actually a single, large form, not unlike The Well Tempered Clavier of Bach, which probably is one important model for this work. We know that Mendelssohn, of course, was largely responsible for the revival of interest in Bach. And like Bach’s work, it could be considered as a kind of oratorio without words. Well, this is a personal theory of mine — I don’t know if there’s any really scholarly justification for this notion. Maybe not, but that’s the way it strikes me.

DH: Then there’s that magic number of 48 (eight time six in Mendelssohn and 48 preludes and fugues in Bach).

FR: Well, we know that the music that was published in Mendelssohn’s lifetime consisted of the first six books. The last two were put together by the publisher. So whether or not it belongs to Mendelssohn’s original conception I don’t think is certain. Personally, my theory is that the first six books constitute the basic idea, in other words, thirty-six. There are good ones also in the last two, Which makes it very similar to my own piece, which is thirty-six variations on this theme, which is also constructed in six groups of six.

Also these groups of Songs Without Words have a structural unity which is worth considering. Each book begins with a “Frühlingslied” or Spring Song with naturalistic imitations of running water, babbling brooks and so on. Then in several of these groups of six, they end with what he calls a “Venetian Gondola Song” or a barcarole. Now, in romantic mythology, the city of Venice has a symbolic function which you find in a number of places, mainly having to do with death. So in my opinion, this work is a series of cycles describing cycles of life. It’s also full of symbolic leitmotivs. There’s a figure of a descending tritone throughout the entire thing. And of course at that time, these things had symbolic meanings beyond their purely musical function, as we know from Schumann’s work, for example, which is full of symbolism. What these things mean is not to clear, but it’s clear that they mean something.

Now just the very title itself is suggestive. Why would you call something “Songs Without Words?” It can only be that there are words somewhere. Schumann thought that there were words — Mendelssohn just didn’t include them. Now of course, Mendelssohn’s ancestors were Jewish — his father had converted to Christianity, so he was not in that tradition, but he probably did know something about it. And in certain areas of Jewish mystical thinking in the 18th century like Hasidism in eastern Europe, you have this concept of the Nigun, which is a song without words. It’s a form of prayer which comes to you in an inspired state. It’s a tune that has no words. So this concept already exists in earlier Jewish mysticism.

Now I have asked a number of musicologists if they think there is any basis for such connections, and all of them have said, no, absolutely not. (Laughter). But nonetheless, it still intrigues me. Well, in Cleveland I’m only playing the first three books, mainly for reasons of time. But it’s enough to get the larger picture. These pieces are not usually played in one single shot like that. So I think it gives you a chance to see these things from a larger point of view.

DH: How is The People United organized?

FR: If you go to the concert, you’ll be able to read Christian Wolff’s excellent analysis (laughter). It’s too complex to go into right now, I think. It lasts for about an hour, and consists of thirty-six variations on this melody by Sergio Ortega, which was very well known all over the world in the seventies as a symbol of the Chilean resistance.

DH: I read that it was intended as a companion piece to Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations. Have you ever played both pieces on the same program?

FR: No. In fact, I’ve never played the Diabelli Variations. When Ursula Oppens commissioned it in 1975 and I asked her what she was going to play on the program, she said she was thinking of the Diabelli Variations, but she ended up doing something else. One piece that I did study carefully that’s always appealed to me, as it does to many people, is the Goldberg Variations of Bach. But for some reason, the Diabelli Variations have just never really appealed to me that much.

DH: Well, Beethoven does as much as possible with a silly little waltz.

FR: There’s a myth around late Beethoven. A lot of late Beethoven is very good, but a lot of it isn’t, I think. Beethoven experimented with a lot of far-out ideas in his later life. Some of these experiments were very successful and others not. I don’t think the Ninth Symphony is a very good piece actually, especially the last movement. In fact, Beethoven himself wasn’t very happy with it.

DH: We heard eighth blackbird perform your Les Moutons de Panurge last year at Oberlin, and we’re very much looking forward to your concert on Friday.

FR: I’m looking forward to it myself. I haven’t been in Cleveland in a while. I’ve been through there not so long ago, but the last time I performed there was in the eighties, I guess. In fact I played this same piece at the Cleveland Institute of Music in a concert that was organized by a group called Common Works.

Frederic Rzewski’s concert in Gartner Auditorium on Friday, March 19, begins at 7:30. Tickets are $29 ($28 for CMA members). Call 216.421.7350.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 15, 2010.

Click here for a printable copy of this article

March 15, 2010