by Jarrett Hoffman

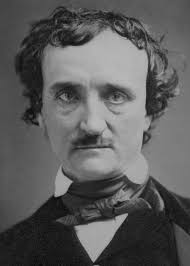

At the heart of the program is Gregg Kallor’s setting of a classic story which recently turned 175 years old: Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart. (Quick refresher for those with only vague memories of high school: the narrator hears the sound of a beating heart coming from under the floorboards…and it’s the heart of the person they’ve murdered under mysterious, grisly circumstances.)

Kallor will take the keyboard part in the Poe setting, joined by cellist Joshua Roman and mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson Cano. They’ll mix and match each other throughout the program, which also includes music by Brahms, Schumann, Hugo Wolf, and John Jacob Niles, in addition to further works by Kallor. Tickets are available online.

Tell-Tale is definitely not a one-off in terms of Kallor’s literary interests. His most recent album, released on October 5 and named after that short story, also includes his settings of poems by Sara Teasdale, Elinor Wylie, Stephen Crane, Mark Twain, William Butler Yeats, and Clementine Von Radics. His first album of songs drew on works by Emily Dickinson, Yeats, and Christina Rossetti, as well as lyrics by Herschel Garfein.

I recently connected with Kallor by phone — he was in Princeton, New Jersey, and said he was enjoying seeing the trees changing color. We began our conversation talking about several dualities in his life: the mix of jazz and classical in his music, his fascination with setting literature to music, and his paired careers of pianist and composer.

Gregg Kallor: Combining jazz and classical — that’s easy, I grew up with both. It happened naturally. It was never really a thing for me until later, when I saw that not everybody had that background. And actually when I got to conservatory, they sort of told me to pick one or the other, and that felt really strange. Sometimes the pendulum has swung one way or the other — the same between performing and composing. And a few years ago they all coalesced into this mishmash of whatever I’m doing now. (Laughs.)

Jarrett Hoffman: How about music and literature?

GK: Actually, that also happened in a natural way. When my first nephew was born, I wanted to write a lullaby for him. I had never written a song — well, that’s not true. I was in a rock band in high school, and I wrote some pretty crappy songs — never a real song.

So I asked a friend of mine who’s both a composer and librettist if he would write the lyrics. He’s a father, and I just thought he would be better able to imbue the lyrics with the warmth necessary for it to be a proper lullaby. He did, and I set them — and I just loved that process so much that I wanted to do more of it. Sadly of course, the intended effect of a lullaby is to put the listener to sleep (laughs), so I was hoping to write something for a more demonstrative audience.

I had to find other texts, and to be honest I didn’t have much of a background in poetry, so I gave myself a crash course. I bought an anthology of English-language poetry and started thumbing through, and Emily Dickinson just jumped off the page and changed my world. From that point, it was just a matter of finding the poems that spoke to me, but that also suggested some musical impetus.

JH: What is it in a poem that does suggest that musical impetus?

GK: It’s nothing specific — it’s more of a feeling I get, and I suppose that could change on any given day. I don’t like artifice — I like things that are the purest, most essential forms of themselves. But at the same time, they can’t just be earnest. They also have to have something exquisite about them. It’s the rare ones, for me anyway, that have that combination of both deep, emotional truth and also some kind of elevated, compelling quality. And you know, sometimes I just like the dirty poems, or the funny ones. I can’t help it, but I’m also drawn to the ones about death or grief or deep love.

JH: Death certainly brings us around to Tell-Tale Heart, which is notably a short story rather than a poem.

GK: I had set a bunch of poems just as short-form songs and in some song cycles, but I had never done anything involving a dramatic, narrative scene. I have a lot of friends in the opera and theater worlds, and to be perfectly honest, for a long time I was not interested in exploring that. But the more I was around it, the more I thought, ‘well, let me dip my toe in the water and see what it’s like.’

JH: Do you think that your setting emphasizes or captures anything that Poe’s story doesn’t?

GK: I think by its very nature, it probably has to. I get very nervous every time I approach somebody else’s text. I try to be as faithful as possible to what I perceive it’s about, but it’s a tricky business because it also has to work on its own as a musical entity — as a new thing. I sometimes get caught being so faithful to the original that some bits don’t end up being quite as effective. So I very carefully go through and try to change it in a way that doesn’t alter the original meaning or idea.

With Poe, I changed maybe one or two words — that was it. It was more of a process of cutting a lot. And of course when I’m setting poems, I don’t change anything. Maybe in the Dickinson I repeated a word once in the entire set.

I just premiered some initial sketches of an operatic retelling of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and it’s the first time I’m taking more liberty with the text. I think adapting a novel from 200 years ago to a contemporary retelling takes a little bit more work. Again, where possible, I’m trying to use her language because it’s exquisite. I think the more faithful I am to that, the more the story will be told in a way that she might be comfortable with.

But to circle back to your question, as soon as you add music to text, you’re going to highlight certain words, phrases, and ideas, and it’ll happen in the way that you respond to the text. It’s my hope that it’s not too narrow of an auditory focus, so that people can still find their own way into the text. But at a certain point, I think you do have to take a point of view, otherwise it will just be too bland to have any meaning at all.

JH: Tell me about your collaborators.

GK: For me, to be able to work with Jen and Joshua is an absolute dream. I couldn’t be any luckier — they are such extraordinary artists, and also such incredible humans. As a composer, I couldn’t hope for a more thoughtful approach to lifting the music off the page, really exploring it, and taking it upon themselves to make it as good as it can be — which is better than I ever thought it could be. I guess I don’t know how to fully express my gratitude that I’m able to collaborate with such wonderful artists who are soloists in their own right — and Joshua is also a composer. They’re playing on the world’s stages, and they still take time out of their busy schedules to come and play with me. It’s unbelievable.

I’m so impressed with the initiatives that he has been pushing. He encourages every artist who comes through to spend several days in residence going to schools and giving performances and workshops all around the greater Akron and Cleveland area. That way, people who don’t have the opportunity or the means to come to the mainstage concerts can share in some of the music.

He’s also started initiatives like providing free transportation and tickets for people who want to come but don’t have the resources. These things seem so essential, and of course they should happen. But it’s so rare, and for him it’s so important. I can’t say enough about him. I mean, he drives to New York from Akron to come hear our performances, just because he wants to be there. He’s quite a man, and he deserves everybody’s thanks.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 29, 2018.

Click here for a printable copy of this article