by Mike Telin

With a program titled “New Beginnings,” Franz Welser-Möst and The Cleveland Orchestra will return in full force to Severance Music Center on Thursday, October 14 at 7:30 pm, for the first time since March 2020. The evening will feature Richard Strauss’ Macbeth, Joan Tower’s A New Day (for cello and orchestra) with Alisa Weilerstein, and Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5. The program will be repeated on Sunday, October 17 at 3:00 pm. Click here for ticket information.

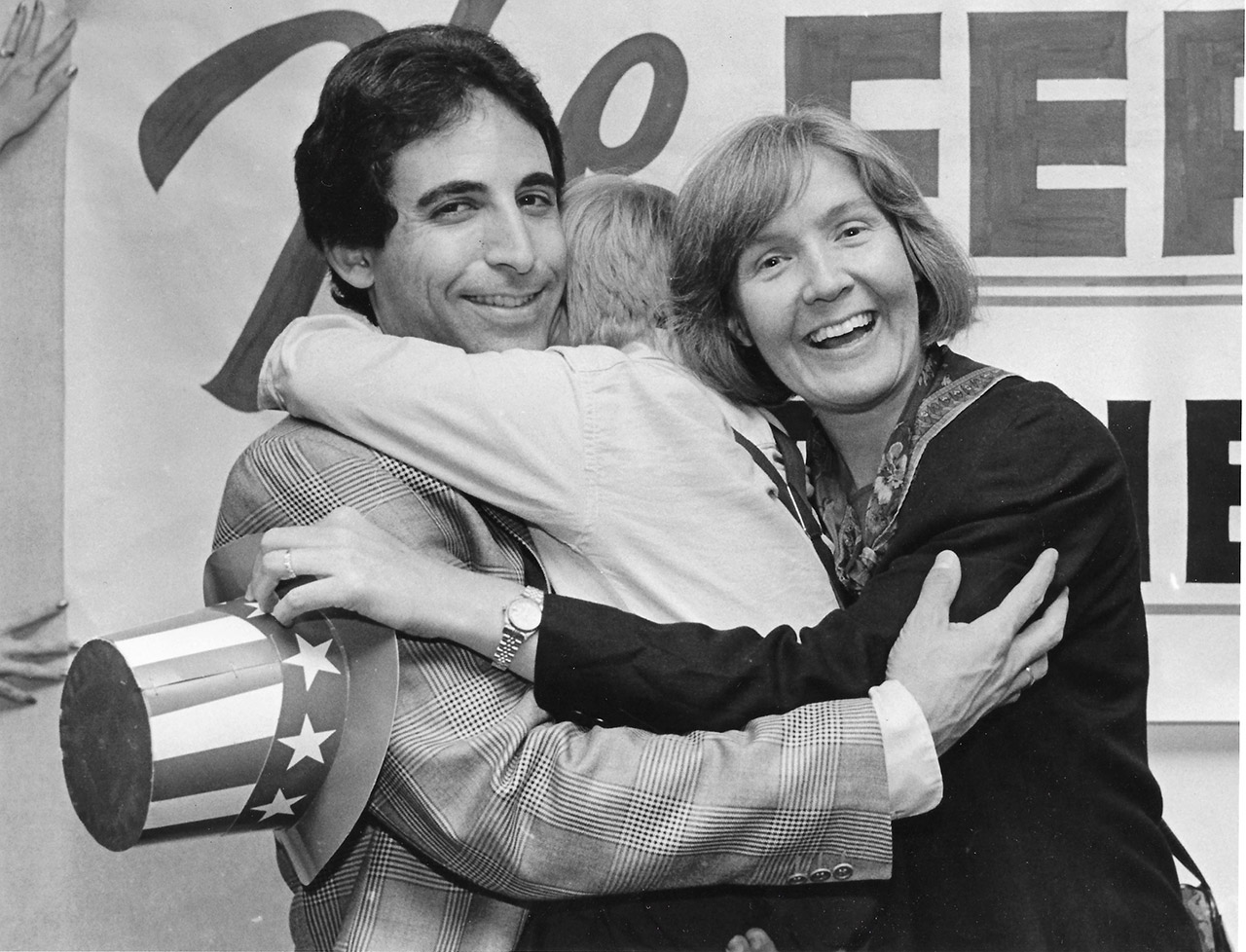

The concerts will also be bittersweet as they mark the final performances of Joela Jones as the Orchestra’s principal keyboard. Jones, whose tenure has spanned 54 seasons, will be presented with the Orchestra’s 25th Distinguished Service Award on Thursday evening. Click here to watch a special video about Jones and listen to a playlist of her most memorable performances.

Joela Jones made her first appearance with The Cleveland Orchestra as a concerto soloist for a Summer Pops concert in 1966. The following year she gave the world premiere of a new concerto under the direction of George Szell, who asked her to join the ensemble soon after. Her name first appeared on the printed roster with the opening season of Blossom Music Center in 1968, and in 1972 she was officially designated as the Orchestra’s principal keyboard player. She has held the Rudolf Serkin Endowed Chair since its creation in 1977.

I spoke to Jones via Zoom and began by asking her about being tapped as a prodigy by Ernst von Dohnányi.

Joela Jones: I was born in Miami, Florida and he was teaching at Florida State University in Tallahassee when I was a child. My parents heard about him through the musical circles of Miami and someone advised them that I should go play for him, and maybe even study with him. So they wrote him a letter and that’s how that came about.

I studied with him for two summers when I was ten and eleven. He was an elderly gentleman at that time and passed away I think three years later.

It was exciting but frightening. I was intimidated by him because when I shook his hand I realized that I was shaking the hand that shook the hand of Brahms.

He was very effusive and told my parents, no more baton twirling or figure skating — and the saddest part was no more accordion playing. I loved my accordion. And they sold it — very sad. It was a beautiful instrument, white with gold keys and gold buttons. I remember that because it hurt.

Mike Telin: But the accordion did return to your life.

JJ: I played it when we did Wozzeck — it has a café band with accordion. I also played it in David Del Tredici’s Final Alice, which we did with Lorin Maazel. I’ve done some Ligeti with Franz. We even used it in Dvořák’s opera Rusalka. When the mermaids sing underwater there is supposed to be a harmonium, but finding a good harmonium in this country is not easy because of the tuning. So I asked Franz if he would mind if we tried with the accordion. He loved the idea.

MT: You’ve chosen a playlist of your favorite concerto performances: was it difficult?

JJ: It was difficult because most performances are sort of like your babies — you cherish them all.

You need to know that I am a romantic at heart so I love the concertos of Rachmaninoff, Chopin, and Schumann. But I chose the slow movement of Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto because of Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos. He was a fantastic conductor and I was so excited because a few years ago he was going to come back in his ripe old age. Unfortunately he was ill and had to cancel and then he passed away, so I was really sorry he never got to come back.

But I remember when I played that movement for him, he said, “I can tell you want to play it even more freely than you are, but don’t worry, take as much rubato as you want. I promise I will be with you.” And he was. So because of him that’s one of my favorite performances.

I had to throw in Age of Anxiety because Bernstein was there even though Maazel conducted it. They were such good friends and it was fun watching them converse. I was in awe of Bernstein, and he was so kind to me — within two seconds he was saying, “Can I call you JJ?” I said sure. The rest of the week in rehearsals he’d say, JJ, can you do such and such there. He was so friendly and warm to me. And that jazz part involves the percussion section, who are all good friends of mine, so I chose that for them. I wanted to show them off because they are such fabulous players.

I chose the Clara Schumann concerto for two reasons. She wrote hers before Brahms wrote his B-flat concerto — which has the cello solo in the slow movement. She introduces the solo cello which then joins the piano for a duet. And I always like to think that’s what gave Brahms the idea to use the cello in a duet with the piano.

The other reason is that [assistant principal cello] Richard Weiss was playing on that set of concerts, so he and I got to play that together — and as you know, we’re married, so it was special to get to play it with him.

MT: In the video, the Orchestra’s chief artistic and operations officer Mark Williams said that you are “the soul of the orchestra.”

JJ: The fact that he would say that is way beyond my understanding, but I also appreciate it tremendously. What has been so wonderful about being part of the Orchestra is that there were so many different aspects that I could be a part of.

On Monday nights, when the rest of the orchestra was off, I had chorus rehearsals where they might be preparing to sing the Mozart Requiem or the Beethoven Missa Solemnis. So I had the privilege of playing those master scores that had been reduced for the piano, and at the final rehearsals I was the orchestra.

The other thing was that all our regular conductors — Maazel, Dohnányi, Franz, and the guest conductors — always had piano rehearsals with the vocal soloists.

Those were in addition to getting to play piano, harpsichord, organ, and celesta in the orchestra. And then I got to play concertos, so I’ve been very blessed.

MT: Franz said that for you, “difficulty meant challenge” Was there anything that made you want to throw up your hands and say, enough?

JJ: (laughs) There have been several very difficult parts that I’ve had to learn. One was the Hans Werner Henze Requiem for piano and trumpet. It’s sort of a concerto for those instruments and orchestra.

There were several things I’ve had to do on short notice, but one that might have been frightening — but I don’t think I had time to be frightened — was playing and recording Messiaen’s Sept haïkaï with Boulez for Deutsche Grammophon.

I remember getting the call from management asking me if I was sitting down. I said no, I was standing. They said, “Perhaps you should.”

[In a 2015 interview with ClevelandClassical.com Jones recalled the event.]

“Pierre-Laurent Aimard was scheduled to play and record Réveil des oiseaux and Sept haïkaï. But I got a call from the orchestra management the Thursday before the first performance, saying that there had been a misunderstanding and his agent had neglected to mention he was supposed to play both pieces. Although he had played Sept haïkaï, he had no time to review it. So they asked me if I knew it — I said no. Then they asked me if I could learn it in time — I said that I would try.”

Jones remembers getting the music that evening, and as luck would have it, the orchestra had been given the weekend off because of Presidents’ Day. “My husband Richard and I were planning to go skiing with our son, so they went without me and I stayed home and practiced about ten hours a day. I remember at the first rehearsal on Tuesday morning I told Mr. Boulez that I had just gotten the music and started learning it on Friday. He said, ‘Don’t worry Joela, it will be fine.’ With his calmness and his beautiful, clear conducting, the performances actually went very well, and we recorded it the following Monday.”

MT: You’ve always held Pierre Boulez in high esteem.

JJ: He was the most brilliant person I ever met. He was so caring toward others — kind and humble, and treated you and your opinion with respect. I’m not the only one who says this — everyone says this about him.

I learned a great deal from him about contemporary music. I had very little knowledge of it until I met him in the ‘70s — Stravinsky was the most modern thing I had heard of. I learned the twelve-tone school of Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg from him and of course many living composers as well. Thankfully he was a strong force in the music world in that direction. He did not want music to become a museum of old composers, and a lot of music has forged ahead because of his forceful personality. And it was just wonderful that he was connected to TCO.

MT: Then there were the orchestra tours.

JJ: There are many wonderful memories, but the height of it was when I was fortunate enough to play Messiean’s Couleurs de la Cité Celeste in the Musikverein with Franz conducting. I don’t think you can get much more elated than that.

As far as where difficulty made something interesting was when we did the Brahms Requiem outside of Linz in the wonderful chapel where Bruckner is buried.

The orchestra was at one end of the chapel, and way down at the other end was a console of an electronic organ that we had to bring in. We couldn’t use the chapel organ because of the pitch — we play at 440 and the organ was much higher.

The performance was filmed, and they didn’t want people to see that the Bruckner organ wasn’t being used. So there were all these people sitting in between me and the orchestra — I was playing with headphones. Everything turned out fine and I believe that when the organ played, they showed the pipes of the Bruckner organ. Franz and the team were happy with the result, but it was quite an experience.

MT: You’ve also been an honorary member of the percussion section.

JJ: They were very nice and tolerated me on a few occasions. They needed a triangle player so I did that for Pictures on several occasions. They also needed a mallet glockenspiel at the end of Daphnis. They were very kind to me and helpful in re-training me how to play those instruments. I had a lot of fun and was honored to be a part of the section.

MT: Looking back from Szell to Welser-Möst, how has the Orchestra changed?

JJ: When I first played with them as a soloist when I was a teenager — this was before I joined — none of the members who are in the Orchestra today were there. So the Orchestra has turned over several times. Maybe not every chair, but many have turned over more than once.

So the membership has changed, but the quality is as wonderful, if not even greater than it was. So what’s so exciting about The Cleveland Orchestra is that if anything, the quality has grown.

The wonderful young musicians that we now have — their work ethic, their musicianship, their attitude toward the orchestra, and their love of music and love of the Orchestra are so evident. And when you have all of that, it makes for a very special community.

I think that community showed very strongly during COVID. It showed how much this orchestra really is a large family — and not dysfunctional like some of them (laughs). It’s a very functional family.

And the great leadership between Franz, the management, and then the wonderful musicians — there’s nothing that will stop the Orchestra from improving, growing, and striving toward perfection.

I think if you go through every music director from Szell on, just the things that they said, and the way that they lead rehearsals, that’s what they were all striving for. Perfection permeates The Cleveland Orchestra.

MT: You’ll be literally going out with a bang with Prokofiev 5.

JJ: (With her signature hand flourishes, she starts singing the symphony’s final bars that feature a prominent piano part.) It happens seven times. Very clever of Prokofiev — very clever. It’s one of my favorites.

First photo by Hilary Bovay, third from WKSU Archives, fifth by Peter Hastings. Second, fourth, and sixth unknown.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 12, 2021.

Click here for a printable copy of this article