by Daniel Hathaway

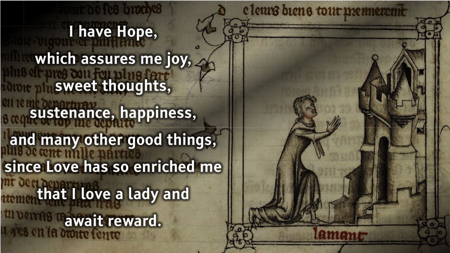

Machaut is responsible for some fifteen such works. They’re preserved in half a dozen illuminated manuscripts supervised by the composer that gave musicologist Shawn Keener plenty of material to work with in designing projections to accompany the story of a young man’s initiation into the fortunes of love.

Love hasn’t changed much in the intervening centuries. Its vicissitudes, ranging from pleasure to pain, are still being discussed — only the platforms have changed. In our day, we communicate our infatuations and our miseries through social media and popular songs. In Machaut’s times, composers used sophisticated poetic-musical forms like the lai, the ballade, the complainte, the rondelet, and the motet.

Blue Heron director Scott Metcalfe introduced the story in French with a nasal, period accent, then turned the narration over to tenor Jason McStoots, who continued in English, alternating monophonic songs with countertenor Martin Near and tenor Owen McIntosh. The three singers came together in that peculiar late-Medieval invention, the motet. An efficient way of saying several things at once, motets featured multiple voice lines each with an independent text sung over a bottom line fashioned out of a chant fragment.

If this sounds like a dry music history lesson, it wasn’t. The music is beautiful, alternating between haunting and jolly, and the narration is engagingly colloquial (“He’s as clueless as a caged bird”). In addition to playing splendidly, the musicians displayed a wry sense of humor, imitating bird songs in a garden scene and making trumpet sounds to herald the beginning of a feast. The first “Kyrie” from Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame made you want to hear this group perform the whole setting. And Estampies that Nagy arranged from other Machaut tunes sounded completely authentic.

With some 4,000 poetic lines, Remède de Fortune is an immense work. Though Nagy and Metcalfe managed to include all its lyrics and music in their concert version, they trimmed the Lai and the Complainte down to a manageable length. They might have thinned it out a bit more to make an intermission unnecessary, but even so, the program is a keeper. Eminently portable, even with projections, it should easily adapt itself to a variety of performing venues. And it makes a terrific introduction to a fascinating musical period that has been explored in academia, but whose artifacts rarely grace concert stages.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 13, 2017.

Click here for a printable copy of this article