by Neil McCalmont

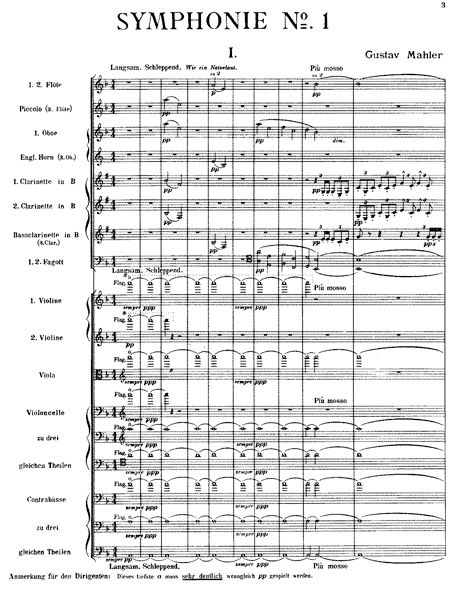

Scoring: Large orchestra

Era: Late Romantic

Length: c. 1 hour

Will you recognize it? Maybe an eerie feeling of familiarity during the 3rd movement

Recommended Recordings: Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic, or Georg Solti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Composer: Gustav Mahler (1860-1911). Mahler was known more as an opera conductor than as a composer during his lifetime, but due to a revival of his music in the 1960s, he has garnered a reputation as perhaps the greatest symphonist since Beethoven. Plagued by anti-Semitic sentiment throughout his career, he still managed to secure the directorship of the Vienna Court Opera, the most prestigious opera house in the world at the time. His turbulent yet successful career continued when he took up posts at the Metropolitan Opera and the Philharmonic Society of New York — now the New York Philharmonic — from 1908 until his death in 1911.

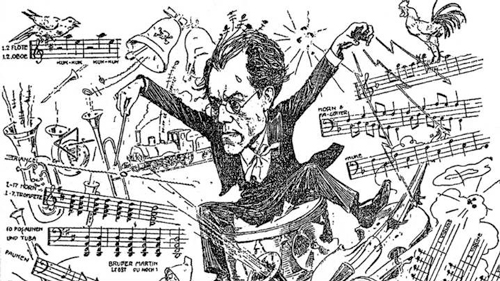

In the summers, he would take to composing in the Austrian Alps, setting up “composing huts” by a lake. His symphonies and song cycles for orchestra are epic, grandiose feats of genius that took him years to write. They require gargantuan-sized forces, and the music itself showcases the most intense limits of emotionality. Listening to Mahler is never your casual stroll through the park; it is always an experience.

The Piece: Any Mahler symphony is a lot to take in during the course of one sitting, but his First and Fourth, each about an hour in length, are his shortest and most accessible. His First follows a literary narrative that he later retracted. The piece draws its subtitle from Jean Paul’s novel Titan, and the fourth movement is loosely based on Dante’s Inferno. We won’t pursue the literary references any further. They’re not really necessary to enjoy the symphony.

The work emerges as from a void. Eventually, bird calls and fanfares are heard from the woodwinds and trumpets, then the introduction erupts into a beautiful springtime extravaganza. The main theme comes from Mahler’s earlier song cycle Songs of a Wayfarer. Mahler often quotes himself, and this instance is particularly giddy. The movement is filled with drunken joy and unattainable happiness (a Mahlerian fingerprint). The second movement is made up of three parts: the first is a jolly dance-like section, then a trio unfolds at a slower pace and softer volume. The third part is a reprise of the first.

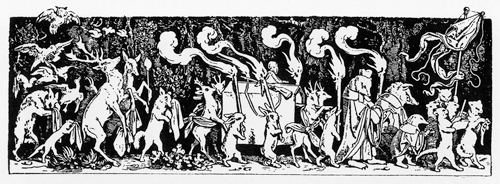

The third movement opens with a minor-key version of the French folk song Frère Jacques. Mahler stated specifically that the image is meant to conjure a hunter’s funeral procession being carried out by forest animals [see below Moritz von Schwind’s woodcut The Hunter’s Funeral Procession, 1850]. This funeral music is contrasted by traditional Jewish klezmer music as the movement’s second theme. The third theme again comes from Songs of a Wayfarer.

The final movement is by far the most challenging to make sense of. Its raging, clashing, and shrieking of fiery noises reflects its subtitle, “Inferno.” The longest of the symphony’s four movements, it is full of radical emotional turns. During the heat of battle, you will also suddenly find yourself in sections of unrivaled tenderness and innocence, and of joyous ecstasy. The conflict continues to grow ever more intense until the final bars prove ultimately triumphant.

Personal Notes: A Mahler symphony is not just a piece of music, but the expression of the composer’s intensely personal philosophy. Just go with what Mahler gives you, and let the symphony’s extreme emotions guide you through the journey. If that journey isn’t your cup of tea, feel free to make up your own narrative. I’m sure your imagination will think of something interesting.

I find this to be the most cinematic of Mahler’s symphonies. You can only wonder if this is one of the sources where John Williams found inspiration for his movie soundtracks.

Fun Facts:

- Originally, there was a movement called “Blumine” between the first and second. After a few performances, Mahler was not satisfied with it and withdrew it. “Blumine” is sometimes performed by itself.

- Mahler’s view of the symphonic genre, and how he attempted to redefine it, can be understood from his quote, “The symphony must be like the world… it must embrace everything.”

- When viewing the Alps from a train, Mahler remarked to his travel companion, “Don’t bother looking, I’ve already composed them.”

Further Listening:

- Symphony No. 4 by Gustav Mahler

- Don Juan and Till Eulenspiegel by Richard Strauss

- Symphony No. 5 by Ludwig van Beethoven

- Siegfried’s Funeral March by Richard Wagner

Published on ClevelandClassical.com June 6, 2016.

Click here for a printable copy of this article