by Kevin McLaughlin

D’Alessio, who teaches at Cleveland State University, makes frequent use of electronic sounds, either in isolation, or in combination with traditional instruments — echoes of Mario Davidovsky, perhaps, his teacher at Columbia. Film is also a favorite medium, affording flights of imagination both visual and auditory.

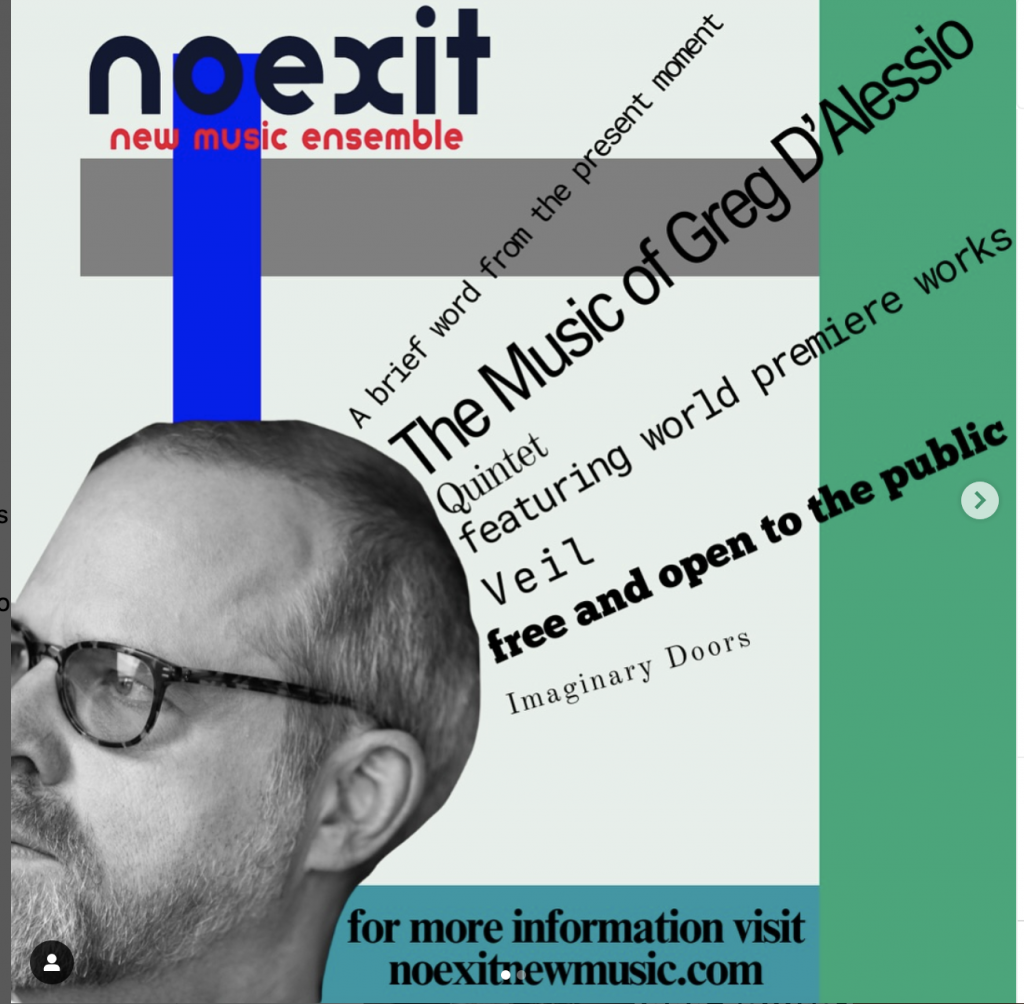

The opening work was the video, A Brief Word from the Present Moment (2025). Moving images and a hyperactive soundtrack combined for what the composer called, “a kind of hallucinatory newscast,” commenting with wide-angled perspective on recent and historical events. An AI-manipulated projection of No Exit Artistic Director Tim Beyer’s talking head narrated, as ancient scenery, medieval paintings, and the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten, paraded past. Combined with frantic music, the effect was unnerving, but partly nostalgic, too — like watching 1980s MTV.

I later learned that the final product wasn’t fully assembled until the morning of the concert, which led to some amplification problems and unintelligibility of the text. I probably wasn’t the only one who was struck by the irony that this technologically reliant performance had more glitches in it than the subsequent human-generated kind.

Quintet, for flute, clarinet, violin, cello, and piano, written in 2024 for five of No Exit’s members, served as an abrupt change from electronic to “regular music,” as the composer calls it. While using five acoustical instruments may have suggested convention, the work’s freshness lay in its communication of diverse instrumental qualities and the player’s personalities. The first movement’s euphoria was indebted to Shuai Wang’s solid pianism and Gunnar Owen Hirthe’s athletic clarinet playing. An autumnal character engulfed the second, courtesy of Sean Gabriel’s luminous flute playing, before the work closed in a lighter mood.

Veil (2001), is a lovely, unhappy thing. It was written at a time when several members of the composer’s extended family had recently died — though, as D’Alessio says in his program note, he doesn’t like to make such cause-and-effect determinations.

The strings begin furtively, moving like shadows in a fog. Violist James Rhodes and cellist Nicholas Diodore, who had tuned their two lowest strings down a half step, made a hollow sound. The deep tone of Gabriel’s alto flute disguised, or at least delayed, his role as soloist, as he intertwined with the others like a fibrous thread. Soon he got a notion, and something like an incantation developed, to which he added a few breathy shrieks for drama.

Diodore took his cue from Gabriel, starting his solo softly before breaking off with wild, thrusting gestures, as if trying to start a fire. Violinist Cara Tweed added greater intensity and Rhodes, liking the idea, answered back. Picking up his C flute, Gabriel quietly steered everyone back into the fog.

The only work on the second half was Imaginary Doors, written for No Exit’s tenth anniversary in 2019. A kind of concerto grosso for multiple soloists with film, it received an extraordinarily precise and communicative performance.

The piece unfolds in eight movements, with the music of the opening Prelude (a stand-alone film) serving as overture, or electronic pre-snatches of the (live) music to come. Images depicted a dreamscape of various scenes — most prominently doors of various condition and splendor (modest, magnificent, and on fire) rolling by.

In the seven remaining movements, four musicians each took turns in the spotlight accompanied by the others. Aside from the demands of the solos, the trickiest thing must have been synchronizing the live playing with the pre-recorded, unrelenting soundtrack. Occasionally Diodore provided a discreet downbeat, but otherwise…woe betide thee if you got lost.

Percussionist Katalin La Favre kept trustworthy time and added brio on marimba, vibes and bells. For extra credit, she made her vibraphone bars sing and shimmer using a cello bow.

Cello and flute solos were outstanding and bass clarinetist Gunnar Owen Hirthe got to apply his patented slap tongue technique. The accruing excitement seemed only to egg on violinist Cara Tweed, who stood to deliver a show-stopping Czardas-like caprice.

Wang perfectly timed her piano chords in the last movement, and La Favre crucially obliged with faint bell and vibe strokes. All commotion ceased, and only the faint whispering of sleigh bells remained.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 20, 2025.

Click here for a printable copy of this article