by Daniel Hathaway

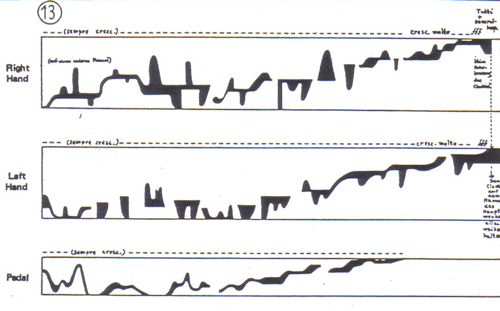

During yet another engaging pre-concert interview, CME director Timothy Weiss held up the sheet music for Ligeti’s 1961/62 organ work, Volumina, while organ professor Jonathan Moyer described what the audience was about to hear. Commissioned by Radio Bremen, the score uses graphic notation — which means that pitches are approximate and open to interpretation by the performer, who is often required bring more parts of his body into action than just fingers and feet.

It’s a noisy, visceral work that begins with a huge, forearms-on-the-keyboard cluster that goes on for many minutes before tapering off into thinner textures. The sound level is ear-shattering when the full organ comes into play. At other points, the heterodyning of low chord clusters makes your ears throb in a different way.

Moyer performed Volumina during last year’s NEOsonicFest on the 17th-century style organ in the gallery of the Church of the Covenant, whose natural wind supply and mechanical stop-drawing mechanism added some special effects to the piece that Ligeti might not have imagined. That instrument sounded as if it had been punched in the stomach when whole-keyboard clusters were played, and its mechanical sliders allowed Moyer to draw and retire ranks of pipes smoothly and gradually.

The Holtkamp’s modern wind supply is rock solid, and ranks of pipes are either on or off, but Moyer and his two student assistants skillfully manipulated the instrument’s stop-changing gadgetry and venetian swell boxes to produce nearly seamless crescendos and diminuendos.

After working his way through pedal glissandos, ghostly murmurs, scampering squirrel music, high-pitched tinkles, blasts from reed stops and a six-hand toccata (plus feet), Ligeti ends Volumina by exploring some of the highest clusters available on the organ — an effect that would drive dogs crazy. It was a wild and exciting ride. Cheers to Jonathan Moyer for stepping in to perform the work when another piece was cancelled.

Ligeti’s 1992 Violin Concerto was proposed and performed by graduating senior Yuri Popowycz, who has completely absorbed its many voices and mastered its formidable technical challenges. Scored for two flutes, oboe, two clarinets, bassoon, two horns, trumpet, trombone, three percussionists and strings, the concerto plays with blending well-tempered pitches with tones that derive from the natural harmonic series but are out of tune with the fundamental pitches of the tempered scale. One violinist and one violist are dedicated to this “scordatura” tuning, joined by hornists who play only notes in the natural overtone series. Ocarinas and slide whistles that can play notes “in the cracks” between piano keys come into the mix from time to time. The idea of non-tempered pitches seems to have suggested itself to Ligeti through a Hungarian folksong based on a scale whose third and seventh pitches are sung lower than their tempered cousins.

The juxtaposing of tunings gave the opening “Praeludium” a sense of “fragility and danger,” just as the program notes promised. The second division of the first movement, “Aria, Hoquetus, Chorale” begins with a folksong-like melody in the violin, then turns suddenly to the “hiccup” effects beloved by medieval polyphonists, and finally ends with a surprising, consonant chord. The third section “Intermezzo” is based on Bulgarian rhythms and ended on Saturday in a riot of sound.

The Passacaglia that follows begins ethereally with long, high notes in the solo violin, to be supplanted suddenly by a super-fortissimo (marked ffffffff in the score, but not quite so hyperbolic in the actual performance).

The final movement of the concerto (“Appassionato”) culminates in a cadenza, originally supplied by its dedicatee, the German violinist Saschko Gawriloff, who fashioned it out of material Ligeti intended for the first movement but discarded. Yuri Popowycz served up a surprise for the CMA performance — a masterful new cadenza composed by his fellow Oberlin student Theo Chandler (Timothy Weiss told the audience about that only after the performance). Chandler’s cadenza fit seamlessly into Ligeti’s musical world and gave Popowycz a final opportunity to play brilliantly before being summarily cut off by the stroke of a wood block.

The concerto seems to have been an obsession for Popowycz, who Weiss told us pasted up a solo part for himself from a miniature score when Ligeti’s publishers refused to send him the real thing. That obsession paid off in a wonderfully committed performance on Saturday, an enterprise to which the Oberlin CME players were equally devoted — and in which they were similarly impressive.

Saturday’s concert began with Feuilles à travers les cloches, a gentle six-minute piece by French composer Tristan Murail, who uses “spectral” techniques — a compositional approach that derives its musical materials from computer analyses of timbres. Taking its title from the reversal of the title of one of Debussy’s Images, it begins pointillistically with high tones that gradually descend and move through two flurries of activity. The precise, sensitive performance was played by flutist Erica Zheng, violinist Julie Suh, cellist Jake Klinkenborg and pianist Chelsea DeSouza.

The afternoon ended with the Cleveland premiere of British composer Philip Cashian’s Three Pieces for chamber orchestra (2004). Scored for two flutes, oboe, two clarinets, bassoon, horn, trumpet, harp, piano, two percussionists and nine string players, the colorful suite takes its inspiration, in turn, from a Spanish Civil War novel, a poem by Sylvia Plath, and a painting by Jean Dubuffet.

Cashian, who was present, described “Scenes from Burgos” as the impressions of an observer wandering around drunk during Carnival in that northern Spanish city, “a series of postcards without transitions.” “The Silver Surface of the Night” was a mini-cello concerto nimbly played by Alex Baker assisted by vibraphonists Daniel King and Michael Mazzullo, who delivered Cashian’s own take on hocket. “The Traveler without a Compass” was, Cashian said, like a machine that layered music on top of each other in different meters.

Cashian’s energetic and ingenious music received finely-honed readings from Timothy Weiss and the Oberlin Contemporary Music Ensemble, closing out its series of five concerts at the Museum this season with a flourish. There will be more to look forward to next season.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com April 16, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article