by Daniel Hathaway

A lot of blood gets spilled during “The Troubadour” in ways gruesomely appropriate to its setting in 15th century Spain. Burnings at the stake, lopping off of heads, scapegoating, revenge and, finally, fratricide are all essential to the plot, along with mistaken identity, an abduction, and a retreat to a nunnery. All of the elements, expressed through Verdi’s dramatic music, endeared the audience to Il trovatore at its debut in Rome in 1853 — they demanded to hear the end of the third act and the entire fourth act all over again.

With the help of his responsive orchestra, Joel Smirnoff led a tight performance of the score. Balances were surprisingly good even though the orchestra pit was raised to floor level.

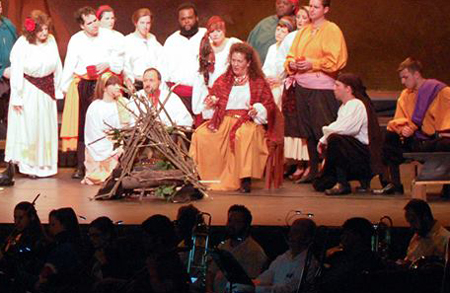

Supporting characters did themselves proud both as singers and actors: Kevin Wetzel as the Count, Brian Skoog as Ruiz, Lauren Wright as Ines, Joel Rhoads as an old Gypsy, and Cory James Svette as the messenger. The male chorus, trained by Jacek Sobieski, sounded magnificent, especially in the opening scene, and the female chorus provided some lovely offstage moments. The “Anvil Chorus” was especially robust.

The singing was more effective than the staging on Saturday evening. Crowd scenes froze the chorus into statuary, and the big scene where the nuns entered holding candles was a bit too picture-perfect in its symmetry. Singers who were supposedly interacting with one another often stood at opposite ends of the stage and faced out to the audience.

That sequence of scenes would pose a challenge for a modern opera house with rotating set capabilities. Designer Charles Gliha chose to suggest each scene through minimal backdrops, lighting, a campfire here, and a clump of bushes there. In a clever move, the back wall of the stage house was nakedly exposed, electrical conduits and all, for the final dungeon scene — out of period, but eloquent.

The painted backdrop of hills for the Gypsy camp had probably once been young and vibrant, but Barbara Luce’s period costumes added essential color to the proceedings — as the festive heraldic banners did for another scene.

Photos by Sean-Michael W. Kvacek.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com June 17, 2016.

Click here for a printable copy of this article