by Mike Telin

On Thursday, October 31 and Saturday, November 2 in Severance Hall, Franz Welser-Möst leads The Cleveland Orchestra and Cleveland Orchestra Chorus in performances of Beethoven’s Mass in C and Messiaen’s Trois petites liturgies de la Présence Divine. Also included on the program is Beethoven’s Grosse Fugue.

The Mass in C was commissioned by Prince Nikolaus Esterházy II. “He was the same person for whom Haydn wrote his wonderful masses. I only mention this because the late Haydn masses are not performed that often either.”

According to history, Esterházy did not like the work — which caused Beethoven to leave abruptly. “Esterházy wrote letters about how much the piece embarrassed him. People have asked me why he thought that and I can’t really answer that either except that he was very accustomed to hearing what Haydn had written.” In his The Life of Beethoven, (1998) musicologist David Wyn Jones recounts, “Nikolaus later wrote to Countess Henriette Zielinska, ‘Beethoven’s music is unbearably ridiculous and detestable; I am not convinced it can ever be performed properly. I am angry and ashamed.'”

But as Porco points out, “Beethoven was Beethoven and he had a lot of new ideas and apparently [the mass] wasn’t what Esterházy had expected. For example, Haydn usually ends his masses in an upbeat manner with a very joyful Dona nobis pacem. Beethoven does that but, in the last minute he reverts back to the very lyrical soft opening, so the piece ends very quietly. Plus, from what I have read, the first performance was not all that good. As usual, Beethoven was making lot of corrections [until the last minute].”

“It is a very special piece that I find interesting on a lots of levels,” Robert Porco says of Messiaen’s Trois petites liturgies de la Présence Divine (Three Small Liturgies of the Divine Presence). A work in three movements with text by the composer, Trois petites is scored for women’s voices, reduced string section, a prominent percussion group and solo piano. “But the thing that people will really remember is the ondes martenot, an electronic instrument that Messiaen liked a lot because of its ethereal, oscillating, other-worldly sound. You don’t get to hear the instrument live very often and while he uses it judicially, near the end it is just magic.”

Another aspect of the work Porco finds interesting is Messiaen’s use of synaesthesia. “The listener can’t really know this from listening, but Messiaen has very specific notes in his score where he says things like “the color here is orange” — or blue, purple or a rainbow, because sounds to him did bring up various colors. I also find his interest in music from all over the world in terms of scales to be fascinating.”

Rounding out the list of reasons Porco is fascinated with the piece is Messiaen’s own text. “I am taken with his Catholicism that is present in almost all of his music. He wrote all of the text and sometimes you have to really work to figure it out. It’s very mystical sometimes and other times very personal.”

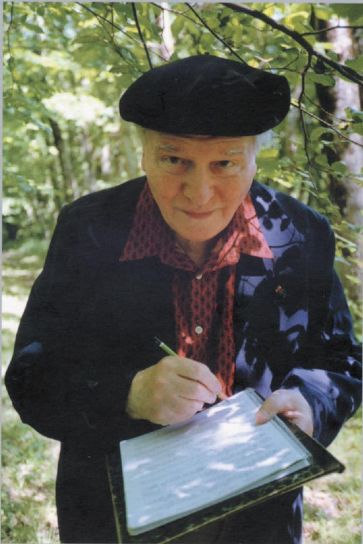

In 2011, Robert Porco was honored by Chorus America with its annual Michael Korn Founders Award for a lifetime of significant contributions to the professional choral art. His achievements across four decades of work have included preparing choruses for such prominent conductors as Pierre Boulez, James Conlon, Andrew Davis, Christoph von Dohnányi, Raymond Leppard, James Levine, Jesús López-Cobos, Zubin Mehta, André Previn, Kurt Sanderling, Robert Shaw, Leonard Slatkin, and Franz Welser-Möst,

Given the level of our collegial conversation, I felt comfortable asking Robert Porco to talk a little bit about what it’s like to be the director of choruses for a major symphony orchestra. After all, once the weeks of preparing the chorus are over, more often then not, everything get turned over to the conductor.

“I’ve been doing this for a long time and I must say that I am absolutely fine with it now. But you’re right, you do the work, turn it over and then go from that to being an audience member. You just have to accept that. It isn’t anything about wanting to conduct it, it’s just that you want to be on the stage making music.”

Porco does add that the level of difficulty in letting go does have a lot to do with the conductor. “But here in Cleveland, Franz knows what to do with the chorus, he knows what he wants and he knows how to work with singers, so it is always fine. But over the years there have been times when I turned the chorus over to someone who I just happened to disagree with a lot. But then you just have to go with it anyway.”

He also says there are a couple of philosophies about preparing a symphony chorus. “Some folks would simply teach all the mechanical things like text and rhythm, then turn it over to do with as the conductor wants in terms of phrasing.” This is not the approach Porco says he prefers. “I find that approach a little bit cold so we try to deliver a kind of finished product to Franz, with the understanding that if he doesn’t like the phrasing he can always change it. For me and the chorus that makes for a far more interesting rehearsal in that we are actually trying to make music. But I do try to build into rehearsals a flexibility with tempos or something else just so we don’t become completely married to a particular way of doing something.”

He also says that over time you learn what certain conductors want. “You do get used to working with people, although no one is entirely predictable. But you get a feel for the kind of music making that they want and I do feel that kind of connection with Franz.” Porco adds, “I love this chorus and we are one of the last standing, entirely volunteer choruses at this level associated with a major orchestra. And what the members bring to it in addition to talent is intangible. Driving an hour and a half each way for rehearsals and performances is real commitment.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 29, 2013

Click here for a printable version of this article.