by Mike Telin

Given the popularity of this concerto, we took the opportunity to once again visit the Orchestra archives to see what archivist Deborah Hefting could tell us about Rachmaninoff’s personal appearance and performance of the piece with the orchestra in 1942. We also spoke to Simon Trpčeski and asked him about the challenges of playing such a well-known piece.

“I need to say that it is a great challenge, as I think it is for any pianist who is playing such a popular piece like the Rachmaninoff 2nd concerto”, Trpčeski told by telephone from his home in The Republic of Macedonia. “One always tries to find something, even if it is a little thing [to do differently] in each performance, since it has been played millions of times.”

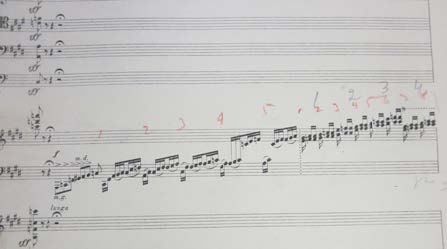

Back to Trpčeski’s comment about trying to find that little something to do differently, he comments that especially in concertos like Rachmaninoff #2, Grieg, Tchaikovsky #1, it is normal for artists to try to put a personal mark on their performance. “I do think that some of the people would go in the wrong way in order to be different, and go beyond the border of logic and the natural dimension in the music. I try to respect the directions the composer has written in the score.”

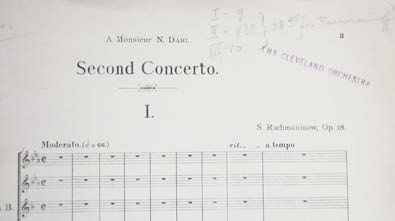

By the time Sergei Rachmaninoff performed his Second Piano Concerto at Severance Hall on January 8 and 10, 1942 under the direction of Artur Rodzinski, the composer/pianist had already established a long relationship with The Cleveland Orchestra, having made his debut as soloist with the orchestra in the same concerto on March 29 and 31, 1923 under the direction of Nikolai Sokoloff. The 1942 concerts also included his symphonic poem The Isle of the Dead (1907), and the recently composed Symphonic Dances Op. 45. (1940).

Needless to say, his return to Cleveland was highly anticipated. The Cleveland Plain Dealer, Cleveland Press, Cleveland News and Akron Beacon Journal as well as local foreign language publications all ran previews announcing the concerts. It’s interesting to note that just before Rachmaninoff’s appearances, Benny Goodman performed a half-classical, half-jazz concert with the orchestra at Public Auditorium on Sunday, January 4, and two days earlier, Artur Rodzinski conducted the Cleveland premiere of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 at Severance Hall.

Cleveland Plain Dealer critic Herbert Elwell wrote, “There was even more enthusiasm when Rachmaninoff appeared in the concerto. As usual he gave to his own music luster and animation that only his brilliant pianism can give it. And it was with evident pleasure that listeners heard from his own hands the drooping wistful melodies that have now reached the domain of popular music.”

reached the full brilliance he has displayed on other visits here, his performance was notable for its emotional values…it was a performance to be remembered.”

Cleveland Press critic Arthur Loesser was unfavorably impressed by the tempos. “It must be said that much of Mr. Rachmaninoff’s performance was on the streamlined side, some of it even seemed to be functioning with a tailwind. Those of us who know this concerto pretty thoroughly had trouble recognizing our friendly note-figures in the rush.” Loesser went on to say, “Great praise must be bestowed upon Dr. Rodzinski…for the highly skilled accommodation of his beat to Mr. Rachmaninoff’s frequent willfulnesses as well as for his success in keeping the occasion- ally heavy scoring in good balance.”

Ten minutes with pianist Simon Trpčeski

Mike Telin: This is your Severance Hall Debut.

Simon Trpčeski: Yes it is. I had a chance to visit the hall and to practice in the George Szell Library when I was there in 2009 for the Blossom Music Festival. It’s very majestic, which is so suitable for this concerto. I am very much looking forward to it.

MT: I watched your performance of this concerto with the Royal Liverpool Orchestra at the Proms on YouTube, and I enjoyed it very much. I can’t exactly put my finger on one thing over another, but you do make it sound fresh and new.

ST: Thank you so very much — and it is very rewarding for the artist when people do notice things, especially because it is such a popular piece. I come from a country where we sing and dance a lot, and apart from the fact that I had wonderful Russian teachers, I really try to sing on the piano and to be as natural as possible. I don’t even know how to explain it or to put it in words. I often say if I was a poet I was going to put what I was thinking in words, but I try to be a poet through the piano.

MT: Is it true that your first instrument was the accordion?

ST: Yes it was. I grew up in a very modest family in a small apartment, I have an older brother and sister so there were five of us and my grandmother lived with us too. This was a very common thing for many families in Macedonia, but I like to quote Pavarotti: “we had so little but no one had more then us.” The warm atmosphere in which I grew up really is priceless.

The way that I grew up was wonderful and the social life was very intense; we were singing and dancing and had family and friends gather- ing every other day. Macedonian folk music is full of uneven rhythms. For us the normal meter is 5/8, 7/8, 9/8, 11/8, all these rhythms that come from our language. I find a connection there with the rhythms and the singing part of the classical music. All of the great composers knew not only the folk music of their nations but also the folk music of other nations and they were inspired by it. I hope that one day you will have the chance to come to Macedonia and experience this small but very beautiful country.

MT: I hope so too. I must tell you that this is the first time I have ever called Macedonia and this call has been very fun.

ST: The first time! [Laughing.l Very good, I feel honored.

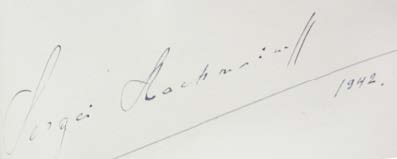

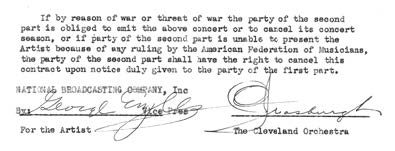

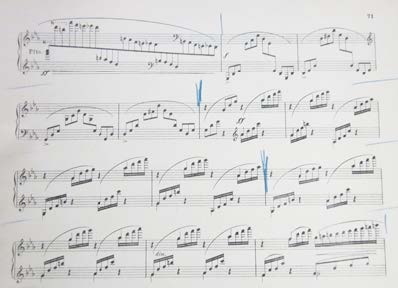

As always, many thanks to Cleveland Orchestra Archivist Deborah Hefting, and to Orchestra Librarian Robert O’Brien for providing the conducting score marked and used by Artur Rodzinsky for the 1942 performances. Photo of Rachmaninoff: photographer unknown. The composer-pianist’s signature is from the Orchestra’s Autograph Book. Below: the addendum to Rachmaninoff’s contract (he received $2,400 for his appearances) reflects the wartime conditions in 1942.

Published on clevelandclassical.com October 23, 2012