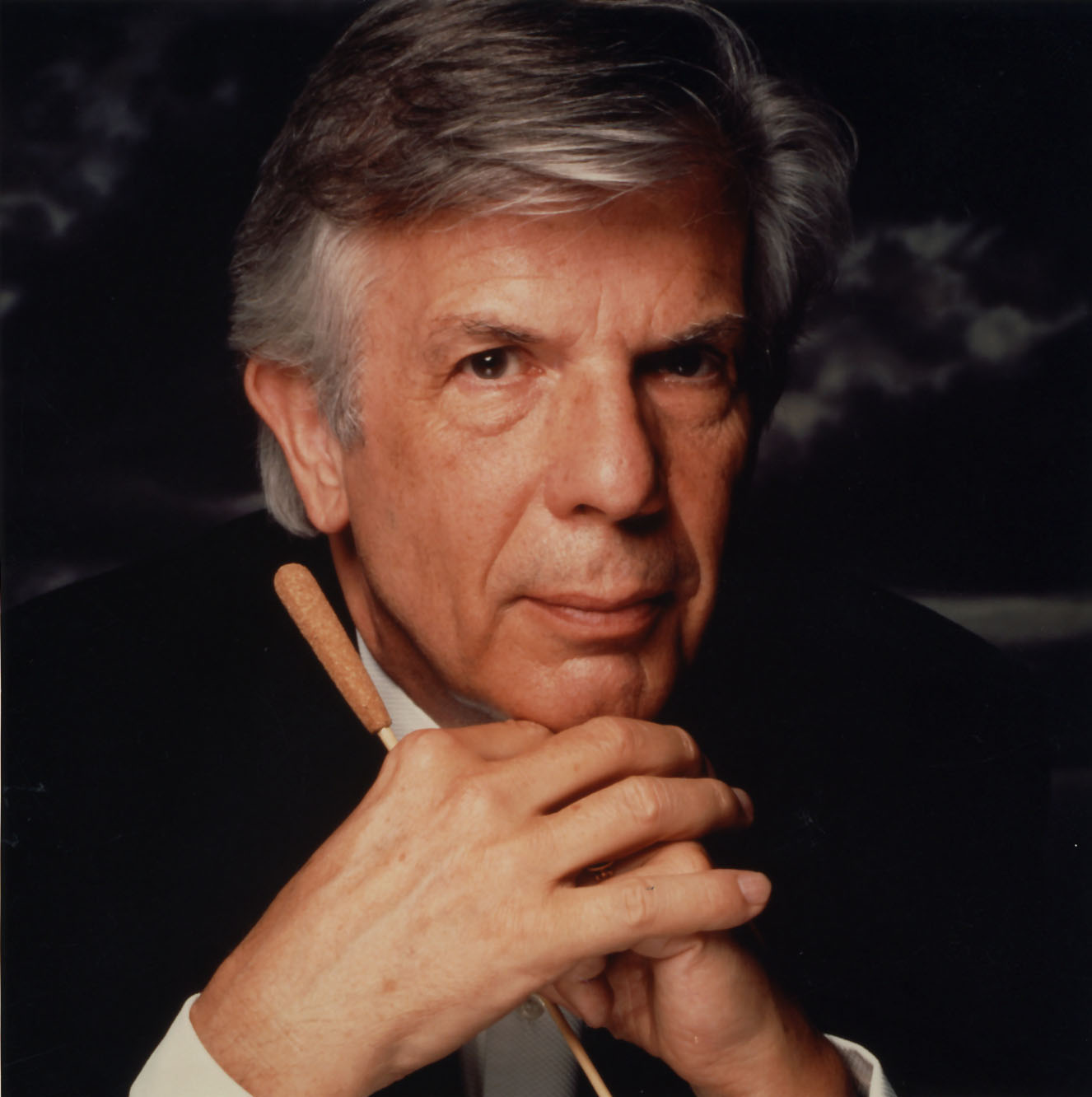

by Daniel Hathaway

Dohnányi conducted the premiere of Henze’s Euripides-inspired opera at the Salzburg Festival in 1966 and led concert performances at Severance and Carnegie Halls in 1990. In 2005, at the conductor’s suggestion, Henze reshaped parts of the third act — where the action turns particularly dramatic — into an orchestral suite entitled Adagio, Fuge and Mänadentanz that covers a wide span of emotional territory in just half an hour. The typically dark and bloody Attic plot, here presented in a libretto by W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman, centers around the king of Thebes who intends to suppress the cult of Dionysus. Instead, he’s seduced by an incarnation of the god himself into spying on the orgies of the Bassarids and Maenads (who include his mother and sisters). Ratted out, he’s dismembered by the Dionysians and his kingdom is destroyed.

Telling this cheerful tale requires a huge orchestra. The Severance stage was crowded with a pair of grand pianos and celesta and a number of supplementary musicians who raised the total of horns to nine, percussionists to eight (plus timpani), clarinets to five and added saxophone and a second English horn to the usual wind complement.

For his visit, Dohnányi also rearranged the string section in his signature fashion, locating cellos next to first violins with double basses behind them, then violas, with second violins on stage left.

Henze didn’t like it when a critic pronounced him as the successor to Richard Strauss, but the impression is unmistakeable. The orchestration throbs with kaleidoscopic color, sometimes brilliant, sometimes hazy, like the murmurs and shimmers that set up the scene. Henze parceled out the opera’s vocal lines to various instruments, who chatter rhythmically or laugh maniacally to represent the ecstatic Dionysian women. A silly waltz suddenly develops, bursts of orgiastic fury come from nowhere, and from time to time textures thin out into a kind of Webernian pointilism decorated by oboe and saxophone solos. Striking chains of ascending and descending chords in the winds recall Verdi’s tension-creating chromatic scales. Just before the end, a conversation between solo cello and bassoon (mere snippets of phrases) yields to a stentorian, metallic tutti.

Though the story line is difficult to follow without words or operatic supertitles, the orchestral writing is so vivid you can’t take your ears off of it. Dohnányi and the orchestra gave the suite a compelling performance in which every detail in a vastly complex web of notes seemed to fall neatly in place.

Following intermission, Dohnányi led from memory Mahler’s Symphony I, famous for its incorporation of an ingratiating tune from Songs of a Wayfarer (“Ging heut’ Morgens über Feld”) and a sardonic takeoff on a nursery rhyme (Frère Jacques). The piece also established the Mahlerian symphonic landscape as a place in which surprising juxtapositions of musical material can occur at any moment.

Dohnányi’s interpretation, while beautiful, tidy and studded with powerful climaxes, was oddly short on that element of surprise. The outbursts of birdsong in the introduction, the sudden inbreaking of Klezmer music, the abrupt returns of previous themes, seemed to be foreseen and predictable.

Among the many standouts in the ensemble were bassist Maximillian Dimoff, who brought an ironic sadness to the minor version of Frère Jacques, and wind soloists Joshua Smith, Frank Rosenwein, Franklin Cohen, Daniel McKelway and John Clouser. The horn section was simply glorious (they stood for their final salvo, as Mahler stipulated) and the brasses crowned climaxes with electrifying tone.

But what about that reseating of the string section? With the highest and lowest strings on one side of the stage and the middle voices on the other with the second violins’ instruments pointing away from the audience, balances sounded odd throughout the Mahler. No doubt that by-now-unfamiliar configuration also led to a fleeting moment of dicey ensemble in the first movement. The audience was enthusiastic, giving Dohnányi and the ensemble a long, warm standing ovation during which the maestro received a welcome back bouquet from assistant principal violist Lynne Ramsey. He graciously regifted it to the blushing assistant concertmaster, Yoko Moore.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 1, 2013

Click here for a printable version of this article.