by Nicholas Stevens

Yuval Sharon, announced as the company’s first Gary L. Wasserman Artistic Director weeks prior to the run of Twilight: Gods, has earned praise for the vision behind the project, full of surprises yet conceptually seamless. His direction, seen in productions of The Cunning Little Vixen and Pelleas et Mélisande for The Cleveland Orchestra, hinted at a future in which opera’s endless velvet seats go the way of horse-drawn cabs and gaslit cobbles. He cut and translated the libretto as well. Yet the truest masterstroke here was saving Wagner’s dramatic ends from his means, and the epic story from itself. Rather than attempt to transcend the local, utilitarian, everyday, and personal, Sharon and company took these as foundational values.

On level one, placard-bearing guides advised drivers to park in a row, stop their engines, and tune their radios to a particular frequency. Before cellist Jinhyun Kim launched into arranger Edward Windels’s distillation of the score, guests watched mezzo-soprano Catherine Martin fret in silence as Waltraute. Soon, Kim — out of view — launched into what sounded like a lost Bach cello suite, Wagner’s waves of harmony lent quasi-Baroque clarity. Listeners barely had time to savor Martin’s despondent low range and Kim’s virtuosity before moving on, electronic music by Lewis Pesacov rising in the wake of Scene 1’s plea to Brünnhilde to come home.

Scene 3 consisted of narration by Music, with electronics by Pesacov and guides tagging deceased Ring characters’ names in chalk. Scene 4 opened with Maurice Draughn’s harp, John Dorsey’s marimba, and David Taylor’s vibraphone playing music of the Rhine, and three stellar Rhinemaidens — soprano Avery Boettcher and mezzos Olivia Johnson and Kaswanna Kanyinda — in thrilling harmony. Strong yet nuanced as Siegfried, tenor Sean Panikkar proved that he can not just hold his own in, but also bring genuine personality to the role. I turned down the radio volume, and there was his voice, still vibrating in my windshield even as the instrumental sounds all but vanished.

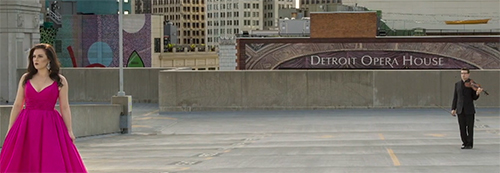

The mere fact that drivers saw a mural reading “Detroit Opera House” upon arriving on the roof for Scene 6 proved among the production’s simplest yet most perfect details. Wrecked cars loomed as a nonet of orchestral players struck up Brünnhilde’s immolation music and the Valkyrie herself — played by soprano Christine Goerke — pulled up in the ten-millionth Ford Mustang, loaned to MOT for the occasion. At best, words can only attempt to capture the feelings conjured as the powerful, golden-voiced Goerke set the corrupt old world ablaze, while a plane towing a VOTE EARLY banner flew by.a

Published on ClevelandClassical.com November 3, 2020

Click here for a printable copy of this article