by Jarrett Hoffman

It bears explaining when headlines have announced the disbanding of a storied ensemble, their Wikipedia entry reads in the past tense, and yet the group appears on the calendar for an important upcoming occasion.

That event in this case is the opening of the Rocky River Chamber Music Society’s 63rd season on Monday, October 4 at 7:30 pm at Lakewood Congregational Church, with an audience both in-person (masks required) and remote, in both cases with free admission.

And that ensemble, performing in Cleveland for the first time, is the German-based Auryn Quartet — founded in 1981, winners of both the London International Competition and ARD Munich Competition a year later — who after four decades have not undergone a single change of personnel.

So, are the Auryn back from the dead? Not exactly. “Corona changed everything,” violist Stewart Eaton explained in a telephone conversation. “We had to delay the final implementation of the ending of the quartet.”

It was Eaton’s idea not only to start the quartet four decades ago, but also to close up shop. “I said eight years ago that I wanted to stop after our 40th birthday.” But because of COVID, he offered his quartet-mates — violinists Matthias Lingenfelder and Jens Oppermann, and cellist Andreas Arndt — to extend a few months. “We’ve managed to recoup quite a few concerts, and our last one will be at the end of February next year.”

The Lakewood performance is part of their final American tour. “Everything is coming around to the last time as we’re winding down, so it’s going to be quite emotional.”

“After I took a few months off from the quartet, I said, ‘Look, we should stop after our 40th. I want to stop when I’m still young enough to enjoy the twilight of my life, so to speak, and maybe do other things.’ And they reluctantly agreed. They said, ‘Yes, it’s better to leave when we want to, at the top of our powers, rather than be pushed off the stage.’”

At the other end of the story, Eaton and first violinist Matthias Lingenfelder met in their 20s.

“We played in the European Youth Orchestra, with Abbado conducting, and we had a fantastic time. We did chamber music as well — we’d have several orchestral rehearsals and then play chamber music ‘til midnight or two in the morning, sight-reading together. And we hit it off very well. I liked his playing, he liked my playing, we liked each other as people. Eventually I suggested to him that we start a professional quartet, and he wanted to as well. He knew the other two from Germany, so I went there, we tried it out, and the rest is history.”

The number 40 was important for the Auryn, in connection to the longevity of their two main mentors: the Amadeus Quartet and the Guarneri Quartet.

“The Amadeus didn’t quite make 40,” Eaton said. “The viola player died before they could reach it. So that was sort of a watershed mark for us, and we’ll reach 41, in fact, when we finish in February. And the Guarneri in their original seating didn’t make 40 either — they changed their cellist.”

Still, the Guarneri made just that one change very late on. “Oh yes, 37 years they were together,” Eaton said. “Incredible. I mean, imagine being with the same people all that time.”

Speaking of which.

“The Amadeus, the Guarneri, and now us — we all seem to have remained good friends,” Eaton said. “You know, everybody goes their different ways after concerts — we don’t always go to the pub together — but we’re civil, good friends, and I think that’s the answer to it. The tolerance and the friendship keep us together. And the music, of course.”

After Eaton’s stroke, there was the question of how the Auryn would proceed in his temporary absence. “I asked them — I begged them — to take on a viola player to stand in for me for that short while, because they would lose all their concerts otherwise. They reluctantly agreed, and that worked out quite well. But when I joined them again, for me it was like coming home, and they welcomed me home, so to speak. It was, you know — the glove fits.”

On Monday in Lakewood, the Auryn will move from f minor (Haydn’s Op. 55, No. 2) to F Major (Beethoven’s Op. 18, No. 1) and back again (Mendelssohn’s sixth and final string quartet, Op. 80).

Close your eyes and imagine a quartet by Haydn and one by Beethoven, and you might be surprised by this particular pairing. “The Haydn that we’ll play is a big, expansive piece, and it’s almost Beethoven-esque in its propensity. It’s quite heavy, especially the first movement,” Eaton said. “But then the Beethoven is almost classical and less Beethovenian because of the lightness of the first and last movements.”

Felix Mendelssohn’s last quartet, written in 1847, pays homage to his sister, fellow composer and pianist Fanny Mendelssohn, who had died in May of that year. “They were almost like lovers — they were so close, and he died shortly after her,” Eaton said. “It’s a tragic piece, and very moving, though all three are moving pieces. The slow movement of the Beethoven is called the ‘Romeo and Juliet’ movement.”

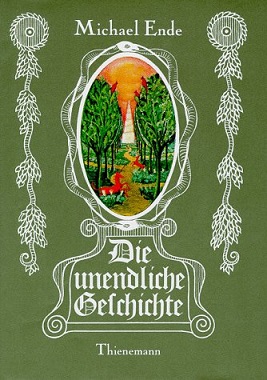

“It had recently been published, and our cellist gave it to our first violinist as a birthday present,” Eaton said. “This was the year we started. Matthias read it, and he thought that phrase Do what you wish was a good motto. The amulet helps you realize your dreams and basically brings you luck, and it seemed like a nice, poetic thing to call the quartet.”

One issue: “Because it’s from fantasy, nobody knows how to pronounce it — even we don’t.”

The author, for one, was in favor of the choice. “We wrote Michael Ende for permission to use the name, and he said, ‘Yes, it’s just coming out in America and Canada — travel around and you can publicize my book!’”

Now, after a career spent accumulating a handful of first prizes, visiting a laundry list of festivals, and amassing a vast catalog of recordings — and perhaps most importantly just playing music with one another for 40 years — it seems clear that Matthias Lingenfelder, Jens Oppermann, Stewart Eaton, and Andreas Arndt did indeed do what they wished.

Top photo by Manfred Esser

Published on ClevelandClassical.com September 28, 2021.

Click here for a printable copy of this article