by Peter Feher

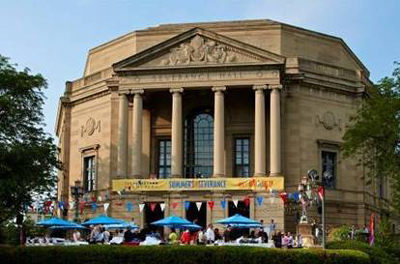

CLEVELAND, Ohio — It’s quite possible that a record number of soloists have taken the stage at Severance Music Center over the past few weeks.

Thursday night’s Cleveland Orchestra concert — a symphonic showcase from beginning to end that spotlighted every section of the ensemble — should certainly count toward the virtuoso tally.

The playing of dozens of individual orchestra members came brilliantly to the fore in Mandel Concert Hall. Never mind that no guest soloist was featured. Rather, the evening’s prodigiousness originated with the lineup of composers, expertly channeled by visiting conductor Christoph Koncz.

Béla Bartók was testing the limits of several different traditions when he penned his Concerto for Orchestra in 1943. Drawing on a lifetime of study that sought to synthesize classicism, modernism and folk music, Bartók wound up setting the standard for a distinctly 20th-century genre with this piece. Combine the scope of a symphony with the demands of a concerto, and you’ve got a dazzling hybrid of all that an orchestra can offer.

Bartók’s score employs each instrumental family to its fullest extent. The organizing principle of his second movement, Game of Pairs, is a series of woodwind duets, yet there’s still space for a couple of drum solos, a chorale for the brass section and a dizzying array of accompanimental string effects. In those six minutes alone, the orchestra delivered a succession of star turns.

Koncz, who was making his Cleveland debut, proved to be a natural partner on the podium. At 37, he may be at the beginning of his conducting career in Europe, but he brings a stellar pedigree as a performer, including 15 seasons as principal second violin of the Vienna Philharmonic. He also earned movie credits as the child prodigy in the 1998 film “The Red Violin.”

Throughout Thursday’s concert, Koncz was a sensitive collaborator in solo passages, while also demonstrating an instinctive command of the full ensemble, coordinating sudden shifts in tempo with quick, rhythmic inhales — as any instrumentalist would. His skills were stretched only when Bartók’s music shifted into complete machine mode, as in the many flying parts of the fifth movement Finale.

But this climax is ultimately engineered to thrill — and to drive home another meaning of the title Concerto for Orchestra: the ensemble as a single tremendous contraption.

For all its sheer inventiveness, it’s hard to believe that Bartók’s score doesn’t borrow at least a bit from Ernő Dohnányi’s Symphonic Minutes, which received a rip-roaring performance from Koncz and the orchestra on the evening’s first half.

Composed in 1933, Dohnányi’s work likewise unfolds in five evocative movements, albeit on a more compact scale. Solo opportunities abound — English hornist Robert Walters especially stood out here — and the suite even concludes with a similarly manic, “perpetual motion” finale.

The program suggested something of an artistic lineage by opening with Franz Liszt’s Les Préludes, the piece that pioneered the term “symphonic poem” in the mid-19th century and that laid the groundwork for much of the colorful, characterful use of the orchestra to come.

The fact that Liszt, Dohnányi and Bartók were all Hungarian-born virtuosos — and that Koncz himself is half Hungarian — just confirms what audiences at Severance have long known: that brilliance can be rooted in place and tradition.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com August 6, 2025

Click here for a printable copy of this article