by Jarrett Hoffman

“That was horrible not to be able to play this piece,” the pianist said during a recent telephone interview. “But.” He paused. “Good things come to those who wait, I suppose.”

Only recently did the opportunity arrive to perform John Adams’ third piano concerto, Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? — written in 2018, and played by only a couple of other keyboardists before Denk was to take it on with the composer on the podium in late March of 2020.

Finally, his first go at it came in Seattle in the early days of 2022. St. Louis is next, in late January. And Cleveland will follow when Denk and Adams share the Severance stage with The Cleveland Orchestra on February 3 (at 7:30 pm), February 5 (at 8:00 pm), and February 6 (at 3:00 pm).

“Now we’re really in the thick of trying to define this piece and make sense of it,” Denk said, “which is so much fun.”

The Adams is joined on the program by two other recent works — Carlos Simon’s Fate Now Conquers and Gabriella Smith’s Tumblebird Contrails — as well as two pieces from the 1980s. Steve Reich’s Three Movements for Orchestra will open the program, and Philip Glass’ “Façades” from Glassworks will be heard in an arrangement featuring saxophonist Steven Banks and the Orchestra’s principal clarinet, Afendi Yusuf. Tickets are available here.

“I really think this piece is a knockout,” Denk said of the concerto, which was commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic as part of its 2018-19 centennial season. “The way that John takes these humble, basic riffs from jazz piano and the general musical subconscious, and creates these colossal waves out of them — it’s kind of incredible. And the more I play it, the more incredible I think it is.”

The slow, second section of this single-movement piece appeals to Denk in an entirely different way. “It’s stunningly beautiful, kind of a virtuoso display of color,” he said. “And it’s not stated enough, maybe, how much John is a lover of harmony — the delight he seems to take in unfolding…a simple chord.”

That’s not an ellipsis of words left out. As he spoke about the piece, Denk slowed his pace at times, or took a pause — not out of uncertainty or to be dramatic, but maybe to match the rhythm of his words to the music he was recalling.

He continued: “And then adding the one…piquant, or melancholy note, and letting the notes resound against each other — I think the slow section is all about that. It’s almost neoclassically perfect in some ways, as opposed to the outer sections which are just demonic and obsessive.”

The ending he finds shocking. “Out of the darkness, it begins to become more and more ecstatic. And then it seems to do a big U-turn.” Denk said frankly that he hasn’t quite figured out for himself what that means. “I tried to ask John, and he didn’t really say, except that I have to play as loud as possible at the end,” he said, laughing. “Which I try to do without injuring myself.”

Speaking of communications between composer and performer, Denk said that Adams has erred on the side of saying less, and seeing what the pianist comes up with.

“I have a lot of ideas about how to inhabit the piece, especially the slow movement,” Denk said. “It’s so beautiful, and there’s so much lyrical possibility in it. I wrote him a bunch of times asking, ‘Can I do this, can I do that?’” Adams’ response was simple: he trusted the pianist to do what seemed right to him, and they could talk more once they met up.

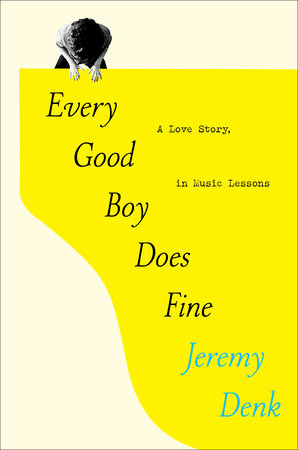

While Denk is an experienced writer — the author of an opera libretto, numerous articles about music, and entries on his blog Think Denk — he pointed out that writing a full-length book “is a whole different thing.”

One challenge of working in this longer form was finding a balance: how much of the book would be about his own personal struggles, and how much would be about the music? That took a while to figure out. “I started the book a long time ago, and then I left it, and then I came back to it,” he said. “Really only in the pandemic was I able to concentrate on it enough to get it to the end.”

Things started moving for him after writing down his memories of a couple lessons — ones that he knew were important, but that took on “a much bigger emotional resonance” than expected as he set them down in words. For one lesson in particular, which took place at his alma mater of Oberlin Conservatory, the structure of a real scene took shape: beginning, middle, climax, ending. “And I thought, that’s really what music lessons feel like,” he said. “Once I felt confident having gotten one lesson down well, I could go on to some of the other parts.”

I told Denk how much I like the title, and how that phrase feels so different taken out of its usual context — a mnemonic device for learning to read notes. His reply: the title wasn’t his idea, and he was very resistant to it for a while.

“But I’m terrible at titles, and now I think it turns out that it’s a very good one,” he said. “If you read the book, there’s a lot of irony and complication looking back at that title — all the perfectionism of my younger years, all the driven-ness, all of that.”

I also told Denk that in the time since he started his blog, my impression is that writing about music has gotten more popular among classical musicians. Was there anyone who inspired him to write when he began, or did he feel he was striking out on his own?

As it turned out, I was overcomplicating things. “I didn’t really think about it that much,” he said. “When I started writing my blog, it was a way to connect to something that I loved, which was books and reading and writing. I always semi-wanted to be a writer, too.

“And it was an outlet to talk about things that don’t fit in an interview like this, or a program note, or a pre-concert lecture. A way to talk in a very strange, digressive, often irreverent way. A way of accessing my happy place — and releasing a bit of the inevitable loneliness that comes from spending most of your day alone at a piano.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com January 26, 2022.

Click here for a printable copy of this article