by Kevin McLaughlin

Film purists who regard cinema primarily as a visual art argue that live music, especially when it emanates from something as grand as a symphony orchestra in a space like Mandel Concert Hall, upsets the balance. Dialogue and car horns stay neatly in the soundtrack, while music — and the emotion it carries — grows enormous and takes over the experience.

Then again…

A live orchestra intensifies the emotions of the soundtrack, heightening everything that touches flesh and spirit. We become newly sensitized to the score. In Herrmann’s case, harmonies and Wagnerian endless melodies compel us to listen more deeply and, in the process, transform the experience.

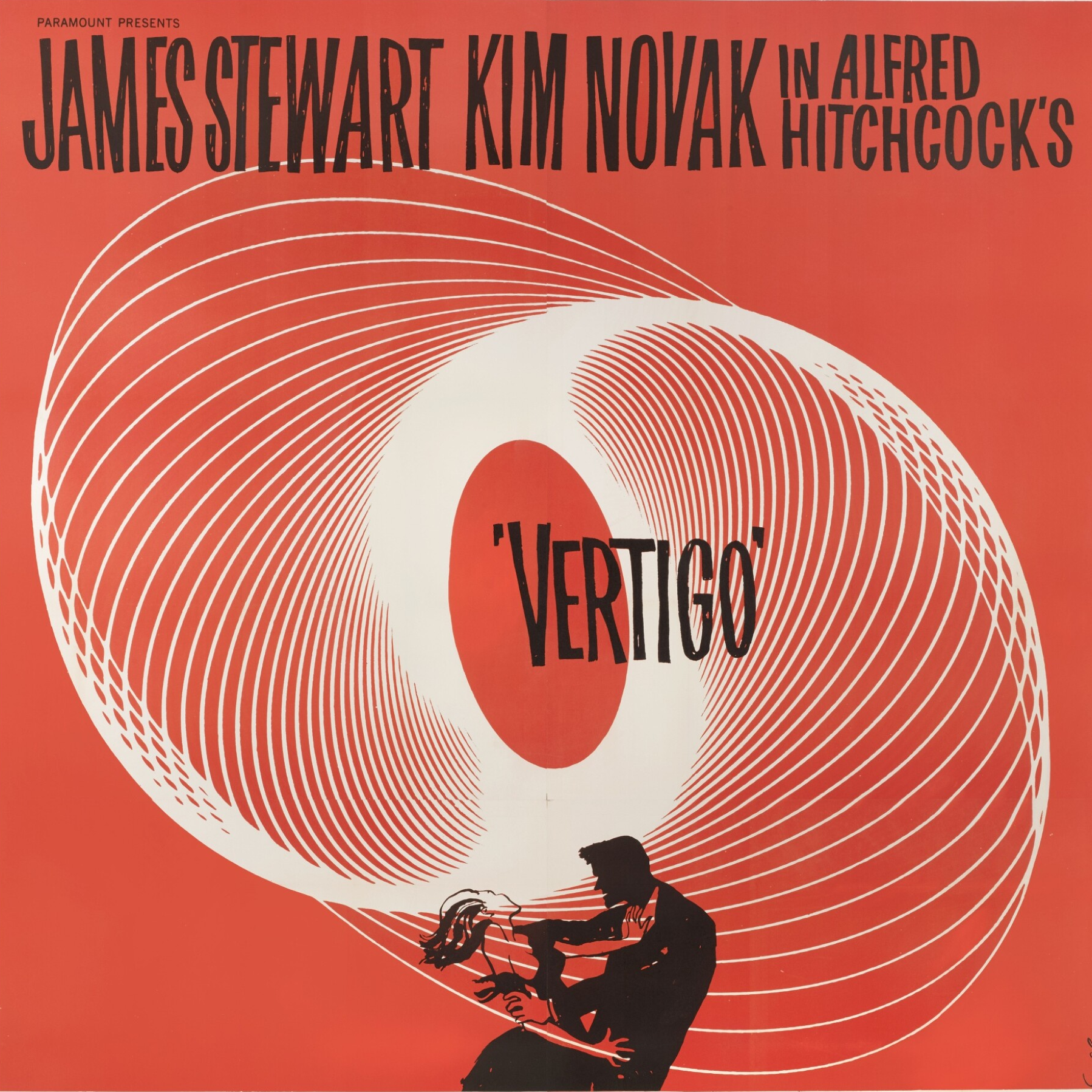

On the screen, we follow Scottie Ferguson (James Stewart), a retired detective pulled into the orbit of Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak) by her concerned husband, Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore). What begins as a routine job becomes an obsession, and we watch — and squirm — as Scottie tries, after Madeleine’s apparent death, to remake another woman in her image, a project doomed from the outset.

Herrmann’s long partnership with Hitchcock rested on shared curiosities — chiefly the human mind and its tricky wiring. The director supplied the plot and camera angles, and the composer supplied the weather inside the characters. For my money, their best work together was Vertigo, where psychology dominates the story and the line between romantic longing and self-destruction is very fine indeed.

Hollywood had already welcomed Wagner into the studio through Steiner’s motivic tags, Korngold’s operatic sweep, and Waxman’s chromatic drama, but in Vertigo Herrmann distilled the style into something unmistakably his own.

Herrmann built the score out of leitmotifs, as if this were an opera. The vertigo motive — chromatic lines moving in opposite directions — evokes the film’s unsettled feeling: always circling, never landing. Scottie’s nightmare introduces castanets and a nervous habanera rhythm, and in the love scenes, Herrmann goes full Wagner — the violins swelling indecorously, a sure sign this romance is headed nowhere good.

Joshua Gersen led a committed, energetic performance. His cues were crisp, and the players stayed in sync. He drew sheen, richness, and volume from the orchestra — enough to swamp the dialogue now and then (thank goodness for subtitles). Another purist’s complaint: dialogue is acting and that’s part of the movie too, but this extra bit of brilliance yielded a year’s supply of passion.

Two sequences — the Mission scene and the transformation of Judy into Madeleine, both among the most Wagnerian stretches in the score, can feel a little goopy in the theater, and don’t get me started on the green lighting. But under Gersen, the music enhanced these scenes, turning full-on operatic just as Herrmann surely meant them to be.

Vertigo remains one of cinema’s most unsettling stories and, in the theater, one of the least believable. On Friday, love’s loss was at times more the musicians’ doing than the screen’s. Gersen and the Orchestra gave Herrmann’s score a kind of second life — overwhelming the film at times, sure, but glorious on its own terms.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com November 18, 2025

Click here for a printable copy of this article