by Lilyana D’Amato

Introduced to African folk art through global imperialism and colonialism, the French became fascinated with racialized depictions of the “savage” Black body, fetishizing Blackness through painting, sculpture, film, and performance. In the early 1920s, avant-garde Parisian artists began appropriating Black culture as a means of exploring what they saw as the juxtaposition between the “primitive” and changing notions of modernity.

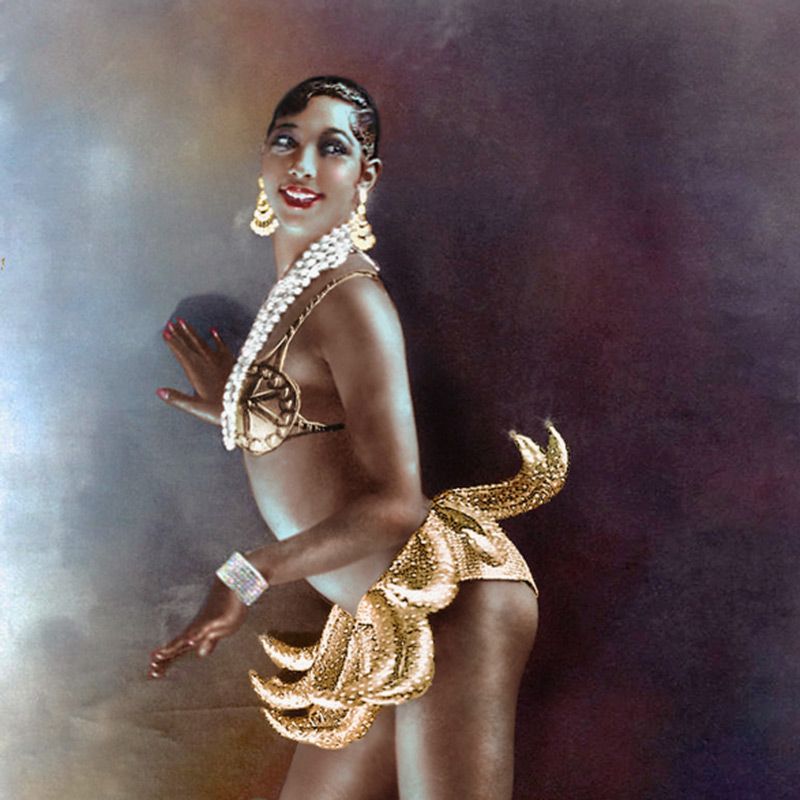

When entertainer Jospehine Baker, the hugely influential African American expatriate, arrived in Paris in 1925, she became the face of this racialized mania. Her body and persona came to signify the exotic, used to satisfy colonialist sexual fantasies.

In reviews of Baker’s most iconic performance, her 1925 stage debut in La Revue Nègre, she is almost solely described through animalistic metaphors — as a monkey, a panther, a giraffe, or a snake. In the Parisian newspaper Candide, the reviewer begins: “This is no woman, no dancer. It’s something as exotic and elusive as music, an embodiment of all the sounds we know.”

Dehumanized and reduced to something, Baker was, as Scholar Alicja Sowinska explores in her paper Dialectics of the Banana Skirt: The Ambiguities of Josephine Baker’s Self-Representation, “popularly situated in a sort of netherworld, suspended between civilization and savagery, and between the human and the animal.”

References to Baker’s ambiguous humanity also appeared in e.e. cummings’ description of La Revue Nègre, referring to Baker’s arrival onstage as the native girl, Fatou. Here, she dons the banana skirt for the first time:

She enters through a dense electric twilight, walking backwards on hands and feet, legs and arms stiff, down a huge jungle tree—as a creature neither infrahuman nor superhuman but somehow both: a mysteriously unkillable Something, equally nonprimitive and uncivilized, or beyond time in the sense that emotion is beyond arithmetic.

French society reduced Baker to her Black body, seeing her only as a tool with which to satiate the male erotic fantasy. Of this, she was well aware. In her autobiography, published in 1996, Baker admitted that she was entertained by the audience’s conception of her: “Primitive instinct? Madness of the flesh? Tumult of the senses? The white imagination sure is something … when it comes to blacks.” They believed her to be a savage woman from deep in the jungle, when in reality she was from the suburbs of St. Louis, Missouri.

Baker was born Freda Josephine McDonald on June 3, 1906. Her mother, Carrie McDonald, worked as a washerwoman, having given up her dreams of becoming a music-hall dancer. Her father, the vaudeville drummer Eddie Carson, abandoned his wife and daughter shortly after Josephine’s birth.

When she was eight years old, in an effort to help support her growing family, Baker began cleaning the houses of wealthy white people in St. Louis, where she was often physically and verbally abused. It was also around this time that young Baker first learned to sing and dance, performing both in clubs and street performances. At age thirteen, she ran away from home to tour the United States with the Jones Family Band and the Dixie Steppers, who performed comedic skits.

After having married in 1921, and quickly divorced that same year, she assumed the stage name Josephine Baker and landed a role in the musical Shuffle Along as a member of the chorus. She gained immediate popularity among the American public because of her comical, minstrel-esque performance and, looking to parlay her early success, moved to New York City. Soon she gained significant notoriety performing in Chocolate Dandies and, along with Ethel Waters, the floor show of the Plantation Club.

However, it was in Paris where Baker came to the height of her fame. She skyrocketed her to international stardom with her performances in both La Revue Nègre and La Folie du Jour. “Wearing little more than strings of pearls, wrist cuffs, and a skirt made of 16 rubber bananas, Josephine Baker descended from a palm tree onstage, and began to dance,” as Morgan Jerkins wrote in Vogue. She captivated audiences with her provocative costuming and performance style.

In this video of a later New York City performance, Baker is noticeably more clothed than she usually was for European audiences. This is worth noting because, while the French may have fetishized Baker as the “Black savage,” she also became a symbol of sexual liberation and bodily autonomy in the decades and century to come. She not only redefined notions of race and gender onstage but also paved the way for modern conceptions of sexual freedom for women.

Baker sang professionally for the first time in 1930, and landed roles in films such as Zouzou and Princesse Tam-Tam. The money she earned quickly allowed her to purchase an estate in Castelnaud-Fayrac, in the southwest of France, where she soon moved her family from St. Louis.

During World War II, Baker worked for the Red Cross during the occupation of France. A member of the Free French forces, she also performed for Allied troops in both Africa and the Middle East. Arguably her most important role in the war effort, though, was her work for the French Resistance. She smuggled messages hidden in her sheet music and even in her underwear. At the war’s end she was awarded two of France’s highest military honors: both the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honour with the rosette of the Resistance.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Baker traveled back and forth from France to the United States to participate in the Civil Rights Movement. Although she had renounced her American citizenship in 1936 — she had visited America earlier in the year and was so disgusted with the racism she encountered there that she immediately filed for French citizenship — she was devoted to demonstrating and boycotting as part of the movement. In 1963, Baker participated along with Martin Luther King Jr. in the March on Washington, lending her stardom and influence to promote global equality. In honor of her efforts, the NAACP eventually named May 20th “Josephine Baker Day.”

In the years just before her death in 1976, Baker performed in America for the first time since repudiating her American citizenship. In June of 1973, the 67-year-old celebrated her birthday with a sold-out bash at Carnegie Hall. As she stepped onto the stage in a glittering ball gown and a headdress of pink-colored plumes which nearly doubled her height, she was met with a standing ovation. Seeing this, she began to cry.

Overwhelmed by this long overdue show of acceptance, she stood for a moment absorbing their welcome before taking off her plumes and beginning a song. Strong and richly enigmatic, her voice embodied theatrical decadence and a deeply personal warmth. A tapestry of French and English, song and dance, reflections and wistful reveries, the performance, officially called “Josephine Baker and Her International Revue,” was the summation of a heroic life, one marked by racism and rejection, but also by love and belonging.

She ended her performance with a declaration of “the Baker philosophy of universal love,” as New York Times writer John Wilson so aptly put it. “I so profoundly love and respect humanity,” Baker said, as she left the stage.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com September 24, 2020.

Click here for a printable copy of this article