by Jarrett Hoffman

On Wednesday, April 20 at 7:30 pm, the Cleveland Museum of Art will receive a visit from the newly formed Triveni, a trio which blends Hindustani and Carnatic (North and South Indian) musical traditions.

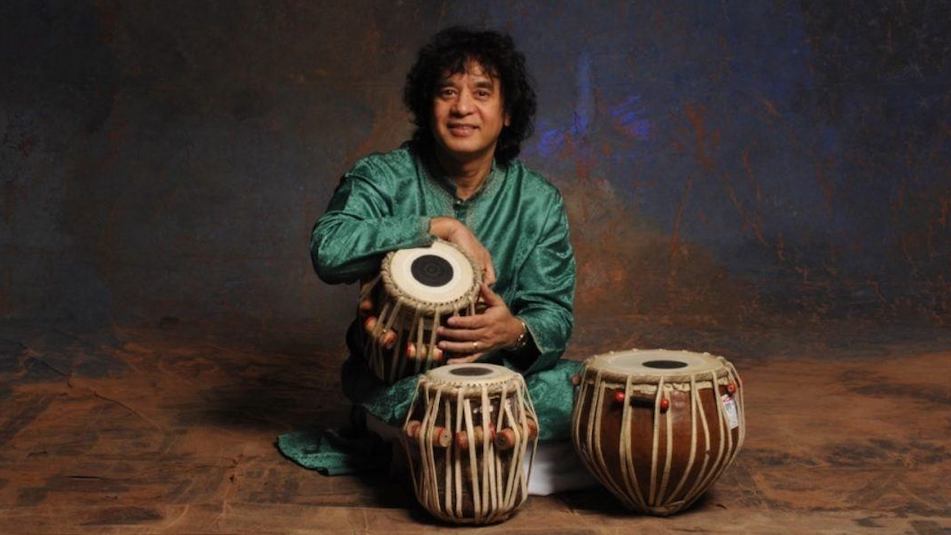

On the violin, and representing the North Indian raga tradition, is Kala Ramnath. On the veena, in particular the lute-like Saraswati veena from South India, is Jayanthi Kumaresh. And on the tabla, mixing rhythmic traditions from North and South to form a bridge on which the violin and veena can meet, is Zakir Hussain.

The concert at CMA’s Gartner Auditorium — tickets are available here — is part of the trio’s inaugural tour, which spans eighteen cities over three and a half weeks. “Not too many off days,” Hussain said last week from a hotel in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

“As with Indian music and with jazz, the band comes together, you have a rehearsal or two and identify the tunes you’re going to play, and then through the tour you refine how those tunes will develop into pieces that will represent the combo that’s on stage. So that’s where we are. We’ve done five shows so far, and things are evolving. We’re getting to know each other really well, and the looks and signals between each other are now becoming familiar, so the improv element of the performance is really beginning to be a lot of fun.”

That comparison between genres continued in our discussion of raga — to put it simply, a framework for improvisation. “It’s like having a vamp,” Hussain said, humming the famous opening bars of John Kander’s New York, New York as an example. “And then out of the vamp comes our song. So raga is the mode, and on that mode are based 1,000 or so compositions, but those are just starting-off points. You play the head, and then you start improvising — and you improvise to your heart’s content until you want to play the bridge, where you improvise on the upper octaves. When you get there, things start to heat up, the tempo rises, and the fun begins.”

In one sense, the trio brings together different time periods as well as styles — and not just within Indian classical music. “It’s interesting to have a more worldly instrument like violin interacting musically with an ancient, 2,000-year-old instrument like veena,” Hussain said.

“And then me with tabla — and for about 50 years of my life having worked with Indian classical musicians, jazz musicians, rock musicians, hip-hoppers, Latin percussionists, and so on. All of that information forces its way into the conversation, but as a trio we’re still able to come out and make a unified musical statement. It’s been very satisfying, and improvising with them is a lot of fun.”

As for going out on tour, I asked Hussain about his experiences performing in different locales, where listeners might have differing levels of familiarity with Indian classical music.

“The amount of information that audiences have is different.” he said. “But in this modern world with all its modern technologies, if I’m going to a concert by musicians I’ve never seen or heard before, it’s easy for me to just Google them, watch them on YouTube, and read about them on Wikipedia.”

Hussain also pointed out that Indian classical music has put down roots in America. “It’s been performed in this country — especially on the East Coast and the West Coast — for the last fifty or sixty years,” he said. “There are people who were young then, whose kids are now grown up and have had information passed down from their parents. And there’s a larger Indian population everywhere now in America. When I was performing here in the 1970s, there were maybe 500 people in the audience, and maybe 20 Indians. Now it’s almost fifty-fifty, and there might be 1,000 people there.”

In any location, some in the crowd will be more familiar with this music than others, creating what might be described as a transfer of energy and understanding. “The reaction from the people who are more familiar kind of drives the rest of the audience,” Hussain said. “If I respond to something good happening on stage, then the guy next to me gets the idea — ‘this is interesting, let me focus on it.’”

Reading the bios of each member of Triveni, you of course learn about their own remarkable careers, but also about their remarkable family backgrounds containing a number of important musical figures — even legends.

“It’s a joy to interact with people who come from that kind of background because there’s a built-in understanding,” he said. “That’s half of it — the other half is being able to make sense of all of that, make it your own, and speak it the way you want.”

Hussain also noted that extensive musical lineages are not uncommon in Indian classical music.

“You find that maybe six out of ten musicians have five or six generations of music in their family. And all of that filters down to this one person, who at age five is hearing the music, watching it, and having this information imprinted on their mind. That’s the case with us, because my father played drums, and in my early days I was sitting in his lap and watching him play — learning, observing, absorbing. Same thing with Kala — her uncle, her aunt, her father. And then Jayanthi — her uncle one of the greatest musicians of South India, her mother one of the finest singers.

“So when that all comes together, it’s like meeting family members you haven’t seen for 100 years. There’s nothing strange or unknown — you just carry on the conversation from where you left off 100 years ago.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com April 13, 2022.

Click here for a printable copy of this article