by Nicholas Stevens

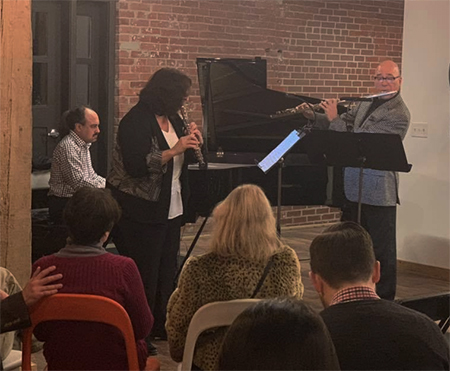

The most emotionally weighty piece on the program came first in this concert held at the offices of WhiteSpace, a marketing firm. Attendees had already sampled hors d’oeuvres and drinks before Urban Troubadour founder Jane Berkner joined fellow flutist George Pope and pianist Eric Charnofsky for David Heath’s chamber suite Return to Avalon.

Having read of the Cathars, a Christian sect of Medieval France that perished amid a decades-long extermination campaign, Heath came away horrified by their fate but inspired by their tolerant ways. The suite reflects descriptions of the Cathars as “Western Buddhists,” with quasi-East Asian pentatonic flourishes throughout. Berkner and Pope blended beautifully in the Debussy-influenced first movement, and a series of crashing dissonances from Charnofsky left behind a shimmering, gong-like resonance at the heart of the second.

The first movement of Blaž Pucihar’s 4 Little Movements found Charnofsky playing syncopated chords reminiscent of “I Got Rhythm” as Berkner musically cartwheeled across this jagged terrain. The quasi-Baroque rhythms and melodies of the second movement melted into the cinematic prettiness of the third, with a spirited jazz waltz serving as a finale.

Berkner took up the piccolo and Pope the alto flute for a series of Bach’s two-part inventions. Playing relentless keyboard lines on a wind instrument comes with risks, but the duo avoided such dangers as slackening tempo or loss of breath in a brief but dazzling portrait of high and low flutes in partnership. Pope remained on alto for his adaptation of echo, Charnofsky’s composition for solo shakuhachi. Breath sounds, flutters, and pitch bends — some of which trailed smoothly into nothingness — demonstrated the sonic kinship between the instruments. Charnofsky returned to the piano to join Pope for Charles Delaney’s Nocturne, an arrangement of a viola piece that recalls Fauré. Each player poured feeling into the work’s decadent melodies.

Daniel Dorff’s Sonatine de Giverny takes impressionist paintings and music as inspiration, but spotlights an instrument that rarely appeared outside the orchestra in the 1910s: the piccolo. Ever in tune despite the instrument’s temperamental nature, Berkner splashed about in the free-floating “Les jardins d’eaux” and fluttered above Charnofsky’s bustling piano in “En ville.”

Tilmann Dehnhard’s Wake Up!! for piccolo pits intrepid high-flute soloists against an electronic alarm clock, conveniently shipped with the sheet music. Like most musical jokes, the piece begins to feel entirely serious after the shock wears off; near the end, Berkner converged with the machine only to soar above in what felt like a victory over the banalities of everyday life.

The concert ended with Piazzolla’s Oblivion and Libertango, run together and arranged for all three players. Pope’s alto proved chameleonic and oddly fitting, here caressing Berkner’s high melodies and there reinforcing the bassline with breathy sensuousness.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com December 4, 2018.

Click here for a printable copy of this article