by Jarrett Hoffman

This time, the first prize winner of the 2014 International Violin Competition of Indianapolis will focus on the Concerto of Samuel Barber — part of an all-American program led by Daniel Meyer that will also include Cindy McTee’s Adagio for String Orchestra and Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring: Suite for Full Orchestra. Pay-what-you-wish tickets are available here.

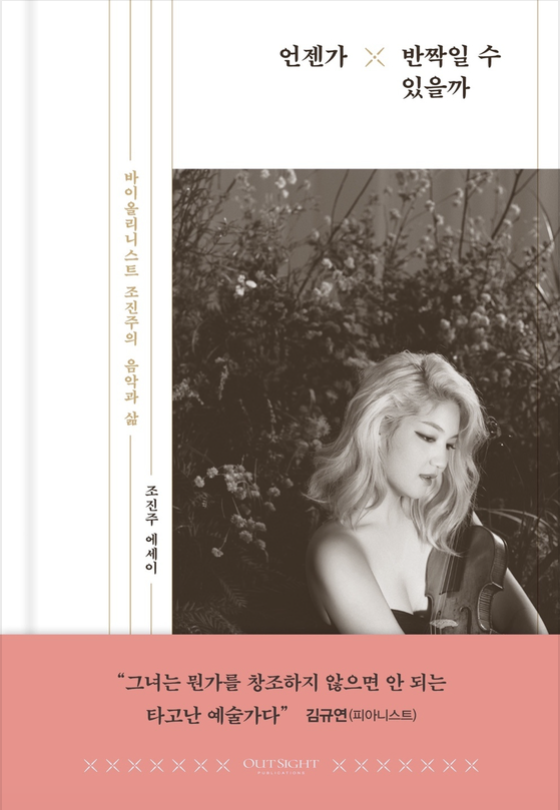

I reached Cho on Zoom after she finished a lesson at McGill University’s Schulich School of Music, where she is Assistant Professor of Violin. Our conversation began with the Barber and ended with her book, Would I Shine Someday, published in 2021. It’s a collection of personal essays covering several topics, including the insecurities of a classical musician, racial discrimination she has faced in the West, how her profession was decided by her parents, and how she has to come to fall in love with this career path that some in the industry describe as their destiny.

Jarrett Hoffman: The Barber Concerto has this funny history where the player for whom it was being written wasn’t very happy about some of the writing. Of course now it’s extremely popular.

Jinjoo Cho: I think the story is that Barber wrote the first two movements, and the violinist was a little upset that it wasn’t technically demanding enough, so Barber wrote this third movement — this firecracker of a movement — almost as a middle finger to the violinist. But it makes it really exciting to have that third movement, so in a way we can all be glad that he did that. It makes it more of a violin concerto in a complete sense.

It’s a beautiful piece. It starts with a gorgeous melody that grabs everybody’s attention, and the second movement is just emotionally so packed, with these intense and visceral moments. And then the third is super exciting and fun to play, kind of like a race-car movement. So I like the piece a lot — I love performing it. And I think pieces like that usually survive — the pieces that are both pleasurable to play and nice to listen to. Those two things usually make the right recipe for a piece to enter the canon repertoire.

JH: Going from the first two movements to the third, do you feel like you have to conserve some energy along the way, knowing what’s coming up?

JC: Well, it’s a shorter concerto compared to a lot of other ones, so in that way, no. But you definitely have to flip a switch for the third movement because the first two are so lyrical, and it just takes a different kind of energy. I think that’s the challenge, the change of pace that you need to channel into very quickly.

JC: I don’t think the translation is available — the publisher was talking about it, but I’m not sure if it progressed beyond that. It’s in Korean, and I actually write quite a bit in Korean — I have an editorial section in a newspaper. It’s always something that I’ve done on the side, because I like writing. But a publisher approached me right before the pandemic and asked me if I would be willing to write a collection of essays. Probably the reason he asked is that I had a series called “Art of Practice” in a performing arts magazine in Korea called Auditorium, where I interviewed various artists of different disciplines.

It was quite a fun series to write because it gave me an opportunity to learn a lot about different artistic processes. And you never get to ask another artist those kinds of in-depth questions — you need the excuse of an interview, otherwise it can be a bit too much. You can’t be like, “How are you practicing the spiccato?” over a glass of wine or something. So it was helpful for my own learning, and I think this publisher really enjoyed reading the series.

But the book became something very different — different chapters on different topics. A lot of it has to do with music — artistic and musical discoveries, and my life events surrounding those discoveries. One chapter is largely about insecurity and the feeling of incompetence that most musicians live with. We basically share daily lives with masterworks, and you can kind of feel crushed by the weight of it all. And the title of that chapter became the title of the book, Would I Shine Someday. It was a meaningful project for me, and I really enjoyed writing it during the pandemic.

JH: Another topic you cover in the book is something I haven’t heard a lot of people talk about. You write about being confused hearing some musicians describe this career as their destiny. I’ve wondered about things like that too — I think for some people it really is true, and for others, maybe even subconsciously, they’re attracted to it as kind of a romantic idea about life.

JC: I think it’s different for everyone. I also think there is a fair amount of fabrication, just because that’s more or less the public image of what an artistic person should be, right? People can’t understand why you would do this thing that is financially unstable, and where even if you have large success, it really doesn’t mean the same monetary reward as in most areas. So I think people are perplexed by it, and we are in a position to have to come up with reasons why this was important in our lives. So then these larger-than-life stories are fabricated and shared in interviews. And I’m sure it’s somewhat exaggerated by journalists also at times.

JH: Sure, I can see that.

JC: It’s possible, right? But as a young person, I do remember finding those statements very confusing — like, how did that person just know from an early age that this was the way it was supposed to be? Because that’s not how I found my connection with this art form. It took me a long time to really understand what I love about it, and I think frankly that I’m still discovering what I love about it.

There is no right way, I think, to decide that this is your life’s path. For me, it’s something that just kind of came to me. I was told that I was talented, so at a younger age I probably enjoyed the attention of that more than anything else. And then it became my life’s work. So it’s interesting how everybody’s affinity for it unfolds differently.

JH: Were there certain things that helped you kind of reconcile with all of this? Or was it just time?

JC: I think there were a couple of life events. Like playing in a string quartet — having that experience of extremely close human connection and seeing how music could be a catalyst for that. It was the same with youth orchestra — having that community of musicians felt really good to me as a teenager. That’s one of the earlier occasions when I felt, okay, this means something to me on a deeper level.

Later on, I think it became more of a lifestyle choice. I realized that I shape my life around having these artistic discoveries, and I like that — that’s something that I cherish and am drawn to. And since I know so much about music already, I might as well have my journey through this art form.

But every day it’s a little different, and there are many different sides of it. I also really enjoy the interpretive side of things, like doing historical research or just figuring out, why is this forte when it was piano before? It’s like a puzzle, and I like problem solving.

JH: When you mentioned how string quartet was really powerful for you, that made me think of ENCORE. [Cho is the founder and artistic director of ENCORE Chamber Music Institute.] There must be some connection there.

JC: Absolutely. Chamber music is more like a life philosophy than just a form of music to me. So it has a really special place in my heart, and I hope to be playing chamber music as long as I’m breathing and introduce it to as many young musicians as possible.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com November 14, 2023.

Click here for a printable copy of this article