by Mike Telin and Daniel Hathaway

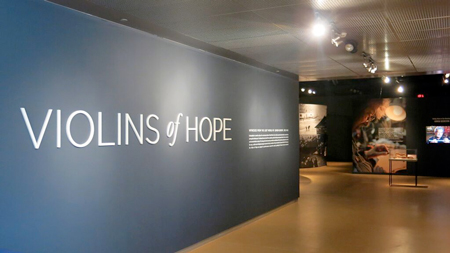

“Living Witnesses from the Lost World of Jewish Europe, 1933-1945

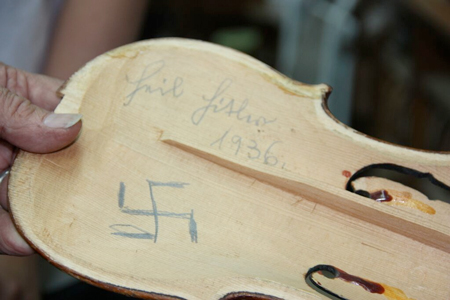

Embedded in Jewish culture for centuries before World War II, the violin assumed extraordinary importance during the Holocaust. The violin released some Jews from captivity under the Nazis while sparing others’ lives in ghettos and concentration camps. For many, it provided a semblance of humanity in perilous hours, and for one a violin even helped avenge murdered family members. The instruments in Violins of Hope are living memorials to all who perished, but during the Holocaust they represented belief in a future in which music, life and beauty would persist.”

The exhibit, which runs through January 3, 2016, includes nineteen violins lovingly restored by Israeli luthier Amnon Weinstein, who brought them back to life as a living memorial to those who perished in the Nazi Holocaust — including some 400 of his own family members.

Click here to see the whole schedule of events planned during the Violins of Hope project.

Photos by Anthony Gray and Sam Fryberger courtesy of the Maltz Museum. Photo of the Heil Hitler violin courtesy of Amnon & Avshalom Weinstein.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com November 19, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article