by Daniel Hathaway

This weekend, music director Franz Welser-Möst will lead The Cleveland Orchestra and Chamber Chorus in three performances of Bach’s St. John Passion, with tenor Maximilian Schmitt as the Evangelist, bass-baritone Andrew Foster-Williams as Christus, and soprano Lauren Snouffer, countertenor Iestyn Davies, tenor Nicholas Phan, and bass-baritone Michael Sumuel as soloists.

As part of Bach’s plan to establish a “well-regulated church music” after his arrival in Leipzig in 1723, he initiated a five-year cycle of weekly cantatas, and planned an elaborate setting of the Passion according to the Gospel of John for performance on Good Friday afternoon of 1724.

On that occasion, the congregation in the St. Nicholas Church (the performance was moved from the St. Thomas Church at the last minute) would have functioned less as an audience attending a sacred concert than as active participants in a liturgical drama — the closest Bach came to writing opera.

In addition to hearing the narrative from the Gospel, sung by the Evangelist and soloists who took the individual roles of Jesus, Peter, Pilate and others, the congregation would have been drawn into the story of Jesus’s arrest, trial, and execution through the exclamations of the crowd (sung by the choir), meditative arias (sung by soloists), and Lutheran hymns that everyone knew by heart (there was a printed libretto to follow, but no hymnals in the pews). And a sermon — a long one, by Lutheran tradition — would be preached between the two halves of the story to further relate the story to the congregants’ lives.

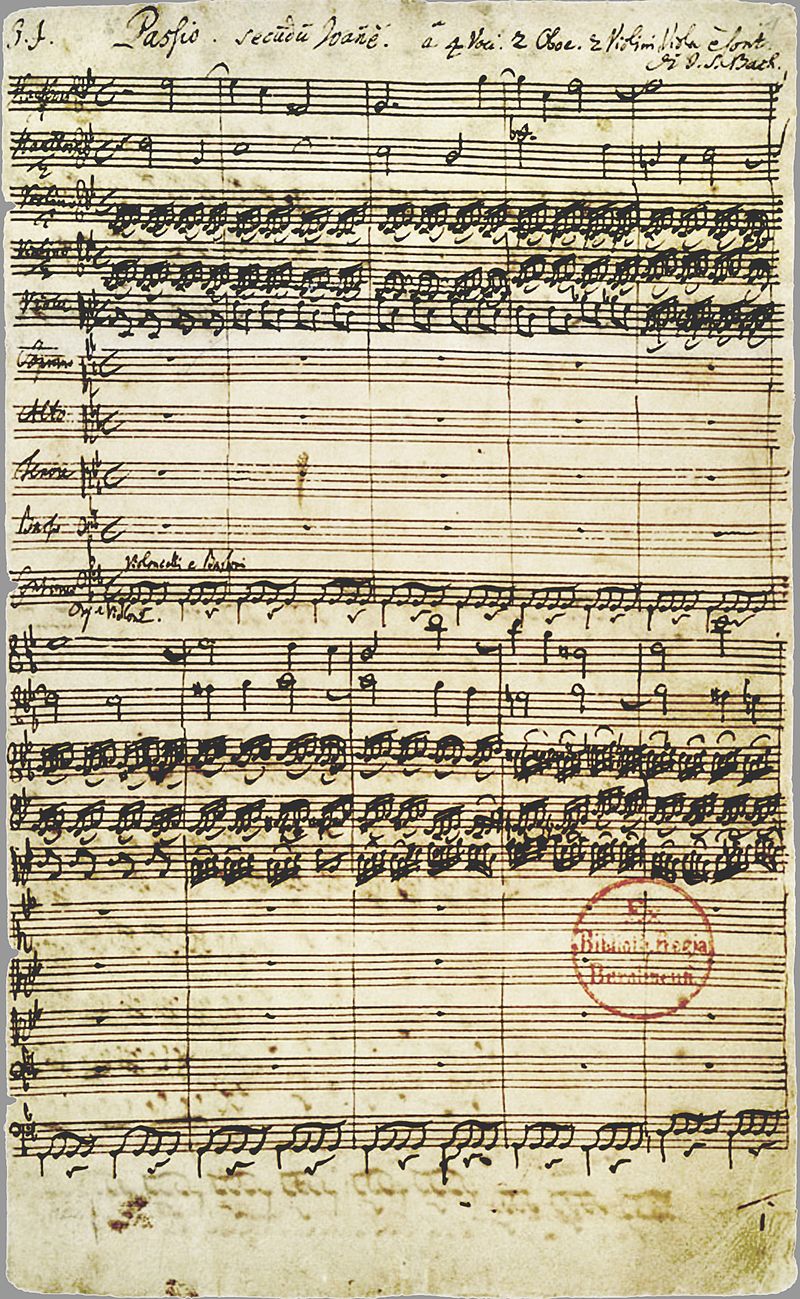

Now as frequently performed in concert halls as in churches, Bach’s St. John Passion has become part of the canon of Western music, an outcome its composer might have had in mind. After making a number of practical and theological revisions of the piece during the 26 years since its first performance, he penned a beautiful fair copy of the final version of the score in 1749.

Much has changed in the world since then. Bringing an 18th century sacred work into a 21st century secular setting like Severance Hall raises issues beyond the details of performance practice. One of the persistent questions about both of Bach’s Passion settings is whether the works harbor anti-Semitic sentiments — were the Jews responsible for the death of Jesus?

Before Bach entered the picture, the authors of the fourth gospel already had uniquely hostile things to say about the Jews, as did Martin Luther in his inflammatory 1543 tract On the Jews and their lies. As a Lutheran Cantor writing a setting of the Passion story, Bach had to deal both with scripture and tradition.

Perhaps he did too good a job. From the foreboding opening chorus, full of turbulence and chilling dissonance, to the seething crowd choruses that scream “Crucify! Crucify!, much of the music is unsettling and challenging. But as Alex Ross pointed out in a recent New Yorker article, the composer has given the listener “a way of coming to terms with extreme emotion.”

During the discussion on Sunday, Marissen pointed out that although the Gospel of John is among the most anti-Jewish of the Christian scriptures, Bach softened those sentiments through arias and chorales that shift the onus of Jesus’s death from the Jews to all mankind. After Jesus’s arrest, a servant of the High Priest strikes him on the cheek for his seemingly insolent response to a question. Who struck the blow? In the hymn that follows, the chorus sings in the name of the congregation:

I, I and my sins,

that can be found like the grains

of sand by the sea,

these have brought You

this misery that assails You,

and this tormenting martyrdom.

Rabbi Klein noted that it’s important to face the ugliness of the world, and Bach’s St. John forces us to confront conflicts within ourselves. How do we we cleanse ourselves of these tendencies? How do we respond to great art that contains disturbing elements?

This short summary of the discussion doesn’t do justice to the nuances of Sunday’s conversation. You can watch a video or listen to the audio of the complete, hour-long session on the WCLV website.

The Cleveland Orchestra’s St. John Passion performances will take place in Severance Hall on Thursday, March 9 at 7:30 pm, Saturday, March 11 at 8:00 pm, and Sunday, March 12 at 3:00 pm. Tickets can be reserved online. The Saturday evening concert will be broadcast live on WCLV, 104.9 IdeaStream and streamed on wclv.org.

Photos by Roger Mastroianni.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 9, 2017.

Click here for a printable copy of this article