by Mike Telin and Daniel Hathaway

“If you look at the makeup of any college vocal studies program, most likely 80% of the students are female,” Field said in a telephone conversation. “Lucretia offers a lot of roles and opportunities for female singers. And singing Britten always makes students better performers. I think it’s the way that the words fit the musical lines so completely. It’s quasi-melodic, yet the singers have to get the pitches absolutely right for it to make emotional sense. The music is rhythmically complex, but not impossibly dense. And like a lot of his operas, Lucretia is lightly scored, so that’s perfect for young voices.”

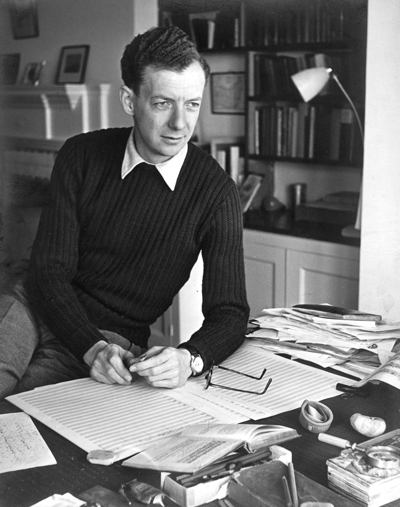

That light scoring — the one-on-a-part orchestration Britten (pictured above) also used in Albert Herring and The Turn of the Screw — is also an excellent educational opportunity for young instrumentalists. In a departure from recent productions, the pit orchestra for Lucretia will be the Oberlin Contemporary Music Ensemble, led by its director, Timothy Weiss.

Another educational dimension the opera offers comes directly from its plot. Based on André Obey’s play Le viol de Lucrèce, works by Livy and Ovid, and William Shakespeare’s narrative poem The Rape of Lucrece, the story relates an actual incident that led to the founding of the Roman Republic, but with some interesting interpretative twists provided by librettist Ronald Duncan. Set in Etruscan Rome around 500 BCE, the story centers on Lucretia, the wife of a general, who is driven to despair and suicide after being raped by a prince. In Duncan and Britten’s take on the story, this ancient pagan tragedy is viewed through the eyes of two Christian choruses: one male and one female.

“The opera deals with the shame, guilt, and agony that caused Lucretia to commit suicide,” Field said. “One of the things I’m hoping to do with this production is to show that the reaction of the characters around her is one of the things that pushes Lucretia in that direction.”

Field’s fascination with the way those characters react has inspired his conception of the two choruses. “In most productions the male and female chorus end up forming a unified front, but in my production they actually veer apart. As the piece progresses, the female chorus beings to empathize with Lucretia more and more. And even in spite of all the religious speeches, the male chorus remains male in its reaction.”

Field noted that Lucretia is rarely performed, but that the opera has recently received several college productions. “Juilliard and a couple of other schools did it last year and I am wondering if that had to do with the release of President Obama’s report about the high number of sexual assaults happening on college campuses?”

In fact, Oberlin is using the opera as an opportunity to open a discussion on the topic of preventing and responding to sexual misconduct, and the college has planned events around the production. A panel discussion, “Violence and Virtue: Framing Lucretia in the 21st Century,” will focus on the significance of the production in contemporary America and in what ways it can provoke productive conversations (Wednesday, November 11, at 4:30 pm in Stull Recital Hall — note change of day).

In the case of Lucretia, Lasser pointed out that rape is really about men jockeying for political position through sexual acts to women who really have no say in the matter. “Lucretia is just an object. When we hold that up to our understandings of sexuality and sexual autonomy and the meaning of consent in the 21st century, all of this opens up a possibility to really talk about how we prevent sexual violence in the 21st century. How do we help ourselves as a community and as a nation grow towards understanding the place of notions of consent? And how do we empower our young people to move that forward?

“I’m really happy that the opera production gives us the opportunity to broadcast information about PRSM — Preventing and Responding to Sexual Misconduct,” Lasser said. “It’s an annual training program that helps students learn to identify and intervene in difficult situations that might lead toward sexual violence.”

Oberlin English professor Nicholas Jones will join two of his faculty colleagues in a lecture on “Women in the Ancient World,” with references to works in the collection of the Allen Memorial Art Museum (Thursday, November 12 at 12 Noon in the Museum).

“Three of us are going to have a conversation in front of the painting, The Death of Lucretia, that the Allen owns. Our goal is to frame this story of double trauma in a context in which it takes on meaning that is both personal and political, and social and cultural. We’ll talk about the Lucretia story in several contexts. Chris Trinacty, a classical professor, will talk about the classical stories in Livy and Ovid that the story comes from. Andaleeb Banta, who is curator of European and American Art, will talk about the use of Lucretia in Renaissance art as an exemplum of chastity.

“I’m going to talk about Shakespeare’s long narrative poem The Rape of Lucrece — which many think the opera is based on — and the difference between Shakespeare’s and Britten’s version of the story,” Jones said. “Shakespeare made it tragic in a formal, noble way, but without any immediate political meaning. For Britten, it had to do with the struggle against tyranny in World War II. The fate of Lucretia becomes a symbol for so many of the victims of the war. I think the early scene where the husbands get drunk and banter their wives’ chastity around is for Britten like the superpowers of Europe playing with the fate of the marginalized.”

Jones added that one of the reasons for the discussions is that the opera dramatizes personally traumatic experiences. “One of the things we talked about was not to downplay those personal and traumatic aspects, but to add further aspects of historical and cultural struggles that the opera introduces.”

On Wednesday, November 11 at 6:30 pm in Hall Auditorium, a panel discussion, “Reading Britten — The Rape of Lucretia in Context,” will bring together Danielle Ward-Griffin (a musicologist from Christopher Newport University), Jonathon Field (stage director), and Andrew Pau & Jan Miyake (Oberlin Conservatory music theorists).

Published on ClevelandClassical.com November 9, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article