by Robert Rollin

The inspiration for the film came from Chaplin’s reading about the 19th-century Donner Party, a group of pioneers who traveled to California in a wagon train. He combined this grisly, true-to-life tale of snowstorm starvation and forced cannibalism with the story of the Yukon Klondike Gold Rush as a backdrop for the movie. As a result the film contrasts slapstick comedy with the harsh realities of Arctic privation.

The Gold Rush was the highest grossing comedy of the silent era, and Chaplin referred to it as “the picture I want most to be remembered by.” At nearly one million dollars it was also the most expensive comedy made in the period. The American Film Institute listed it three times (in 1998, 2000, and 2007) among the best 100 films ever made.

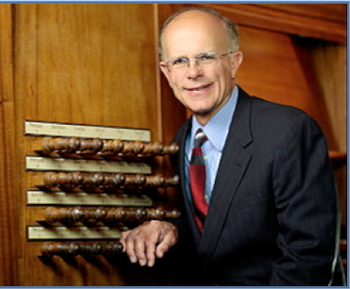

Todd Wilson set the mood for the screening with his prelude: selections from the contemporaneous Broadway musical No, No, Nanette (1925). Vincent Youmans’ Tea for Two, one of the most popular and tuneful songs of the era, dominated Wilson’s charmingly performed vignettes. As promised in his short spoken introduction, Wilson soon segued to Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in d minor, which powerfully suggested the eeriness of the Halloween season and led into the opening credits.

The byzantine plot follows Chaplin, the Lone Prospector, along the Chilkoot Pass as he stumbles upon the renegade Black Larsen’s cabin during an icy blizzard. Just as Larsen is about to throw him back into the perilous storm, prospector Big Jim McKay appears, subdues Larsen, and sends him into the storm to find food. The two prospectors set out to reach McKay’s hidden mine, but Larsen has already found and taken over the claim. Larsen knocks McKay out with a shovel, causing him to forget the mine’s location.

The Lone Prospector’s outlandish appearance makes him the target of pranks and gibes when he arrives in one of the boom towns. Catching sight of Georgia, queen of the dance hall entertainers (played by Georgia Hale, Chaplin’s wife), he immediately falls in love with her and declares that love to the puzzled Georgia. Just then, Big Jim returns to the town with his memory partly restored, and upon recognizing the Lone Prospector, enlists his help to return to the lost mine, promising him an equal share.

During the silent era, theater organists played well-known melodies to suggest mood changes in the film. Wilson applied this technique to perfection in the performance, using a simple, almost naïve tune composed by Chaplin and associated with the Lone Prospector’s charm and innocence. Other simple melodies included Loch Lomond, Coming through the Rye, Auld Lang Syne (used in the New Year’s Eve scene), Brahms’s Lullaby, and Turkey in the Straw (for lighter moments).

Early in the film Wilson used Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus music to depict the excitement of Larsen discovering the gold mine. He played Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries to reflect the perilous moments when the cabin teetered over the precipice. Throughout the afternoon’s performance, Wilson’s energy, cleverness, and grace were exceptional.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 27, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article