by Jarrett Hoffman

CELEBRATING BLACK COMPOSERS:

In honor of Black History Month, The Cleveland Orchestra has shared the complete playlist from its January MLK Community Celebration. That included three new performances of solo and chamber music filmed for the occasion:

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson’s Lamentations for cello (Mark Kosower),

Leslie Adams’ L’extase d’amour for viola (Eliesha Nelson) and piano (Dianna White-Gould),

Florence Price’s Adoration, originally for organ, arranged here for clarinet (Afendi Yusuf) and string quartet (violinists Stephen Rose and Jeanne Preucil Rose, violist Lynne Ramsey, and cellist Mark Kosower).

Kosower writes of the Perkinson work:

[It’s] a tremendous piece of music. It’s so interesting because Perkinson takes European Baroque counterpoint and combines it with American romanticism and the music of his African-American heritage, such as Black folk music, spirituals, and jazz. All of this is synthesized in this four movement work which, like the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, speaks to a much wider group of people of all nations, backgrounds, and cultures.

And on February 11, the Cleveland Chamber Choir commemorated the anniversary of the passing of composer and arranger Moses Hogan by sharing a performance of his Hear My Prayer. That composed spiritual — with both words and music by Hogan — was recorded by the Choir virtually in November.

Click that link to listen, and to read a tribute by musicologist Charles McGuire, who writes that Hogan was “one of the twentieth century’s most influential composers and arrangers, especially of spirituals.”

McGuire goes on to lay out the path of Hogan’s life and career — from his immersion in choral music during his childhood in New Orleans, to his initial desire to be a concert pianist (including in studies at Oberlin Conservatory), his founding of the New World Ensemble (later the Moses Hogan Chorale), and his rise in popularity to the point of becoming “the leading expert on spirituals and their arrangement.”

And speaking of Hogan, there’s one local event on the horizon to take note of. Oberlin will host a free panel discussion on Zoom on Wednesday, February 24 at 7:00 pm titled “Moses Hogan ’79 and the Evolution of the African American Choral Tradition.” It’s hosted by DaQuan Williams, creator of the Moses Hogan Sing-Along. Click here to read about the panelists, and here to register to attend.

Whether as additions to your playlists, programs, and music stands, or just to hear new interpretations of great music you already knew, have a listen to the four works featured above by Hogan, Perkinson, Adams, and Price.

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

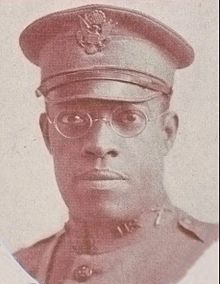

Among the figures in music history to celebrate today is one who deserves a great deal more recognition than he gets. American composer, arranger and bandleader James Reese Europe was born on February 22, 1881 in Mobile, Alabama, and has been dubbed “the Martin Luther King of music” not only for his compositional and orchestrational innovations, but also for his leadership as a Black musician in New York City in the early 20th century.

That leadership included forming the Clef Club in 1910, an organization that housed its own orchestra and chorus, in addition to serving as a union and contracting agency for Black musicians. One famous performance by the Clef Club Symphony Orchestra came at Carnegie Hall in 1912: a highly successful program that featured exclusively Black composers and an enormous and unique ensemble. Its numbers totaled 125 musicians, and it combined traditional orchestral forces with banjos, mandolins, and guitars.

Carnegie Hall has termed that concert “day one of jazz” at the venue, while acknowledging that the description might be misleading to a contemporary audience:

To modern ears, the proto-jazz mixture of ragtime, blues, and minstrelsy played by the Clef Club Orchestra may not sound much like the jazz most would recognize from 20 years later, but this should not overshadow Europe’s importance as one of the first to translate “syncopated music” to a large ensemble.

The question of Europe’s genre is also tackled by jazz historian David Sager in a 2019 article in The New York Times:

Although historians often associate Europe with ragtime and jazz, his focus was on neither. He wanted to create music that he believed reflected the artistic temperament and souls of African-Americans, whatever style it took, and to use it to promote the validity and viability of Negro musicians.

One example of Europe’s distinct style is his fascinating, four-minute The Castles in Europe (Castle House Rag), one of a series of pieces he recorded in 1914 for the Victor Record Company. That clip, a performance by Europe’s Society Orchestra under his baton, entered the National Registry of Recordings in 2004. (You can read about its origins in an essay by David Sager for the Library of Congress here.)

Serving in World War I proved to be another important chapter in the life of James Europe. As a lieutenant, he led the all-Black 369th Infantry band, nicknamed the “Harlem Hellfighters.” They dazzled France with their unique brand of music and returned to the U.S. triumphantly after the war.

Europe’s death in 1919 was both tragic and senseless. Shortly into the Hellfighters’ post-war tour, he was stabbed in the neck during an intermission by a drummer in his own band. Sources describe the conflict in various terms: the musician seems to have felt he had been cheated or mistreated in some way, and in a fit of anger, lunged at Europe with a penknife. The wound, which seemed minor at first, proved to be fatal. Europe was 38.

A biography from the Library of Congress sums up Europe’s legacy like this:

The impact of James Reese Europe on American music cannot be overestimated…he shaped not only the music of his own time, but of future generations as well. His organizational accomplishments… prefigured the black-owned, black-run musical organizations that have existed since his time and to this day.

And finally, back to Sager, who squares his focus on Europe’s impact on jazz:

During that final tour, a wide range of Americans had begun to realize that jazz was something of which they could be proud. Photos from the [post-war victory] parade, with jazz-playing musicians surrounded by returning soldiers, made it clear that this was a homegrown, even patriotic, art form. The old notion about “jazzing” suddenly seemed quaint. “Jazz” had become a noun.